Originally posted on Twitter on 7 October 2022. There is no day 166, because day 166 on the Twitter version was a spoof post which… well, I don’t feel it particularly landed at the time, and you *really* had to be there for it to even start landing. Anyway, moving on.

Šrobárova was built in 1889.

It was part of Korunní (coming soon enough) until 1947.

Vavro Šrobár was born in 1867 in Lisková (now in north-central Slovakia), one of twelve children.

After graduating from the gymnasium in Přerov in 1888, he moved to Prague to study medicine at Charles University.

When in Prague, he chaired the student organisation Detvan and became a follower of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk.

From 1898, he started publishing the magazine Hlas (Voice), which was highly critical of Hungarian rule.

After running for a seat in the Hungarian Parliament in 1906 (along with Andrej Hlinka), he was imprisoned for a year in Szeged for provocations against the Hungarian nation.

During WW1, Šrobár became involved in the Czechoslovak National Council, which had been set up to liberate the Czechs and Slovaks from Austria-Hungary.

When the Czechoslovak proclamation of independence was read out in Prague on 28 October 1918, he was the only Slovak signatory.

He then became Minister of Health for Czechoslovakia, and was also responsible for the administration of Slovakia as a whole.

From 1921-2, he was Minister of Education and National Enlightenment; after this, he took a post lecturing at the Medical Faculty of Charles University.

During WW2 and the establishment of the pro-Nazi Slovak State, Šrobár took part in the anti-fascist resistance, albeit not as one of its leading figures.

He became co-chair of the Slovak National Council in 1944, and, when the war ended, was appointed Czechoslovak Minister of Finance (until 1947).

He then became minister for the unification of laws, even after the Communist coup d’état in 1948.

He died in Olomouc in 1950 and is buried in Bratislava.

It makes sense that Vinohrady Hospital is located in this street, given Šrobár’s connection to medicine and Charles University.

His contribution to the creation of Czechoslovakia cannot be denied either.

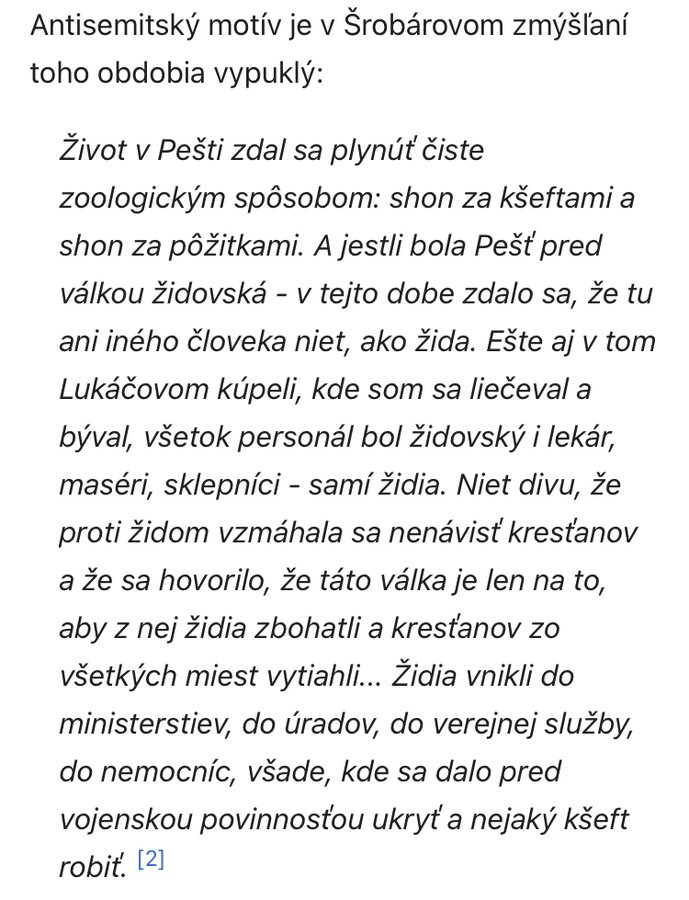

On the other hand, it’s somewhat surprising to see a street named after somebody who clearly didn’t stand up to the Communists, and who, based on this quote from Slovak Wikipedia, was pretty damn anti-Semitic.

Leave a comment