Originally published on Twitter on 30 November 2022.

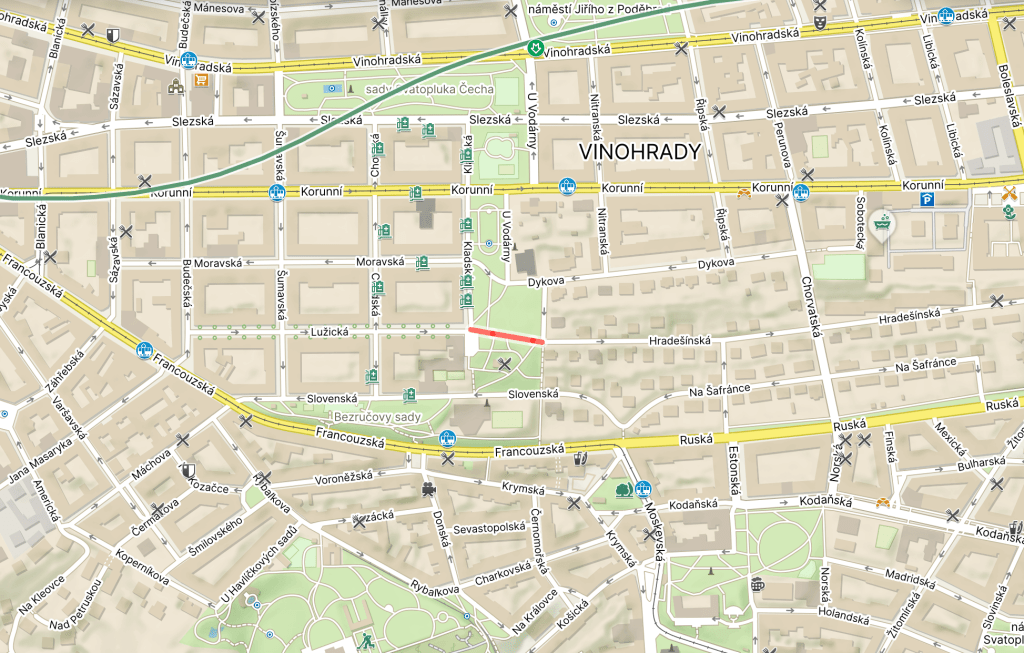

Sady Bratří Čapků was created (sort of) in 2016.

This was part of a larger park, opened in 1903, and, originally called Městský sad (City Garden) until 1928.

In 1928, it became Bezručovy sady, after Petr Bezruč, the pseudonym of Vladimír Vašek (1867-1958), a poet most known for Slezské písně (Silesian Songs), a collection of poems about the people of his native Silesia.

In 2016, the part of the park that’s in Vinohrady / Prague 2 was spun off and renamed Sady Bratří Čapků; the Prague 10 / Strašnice part is still Bezručovy sady.

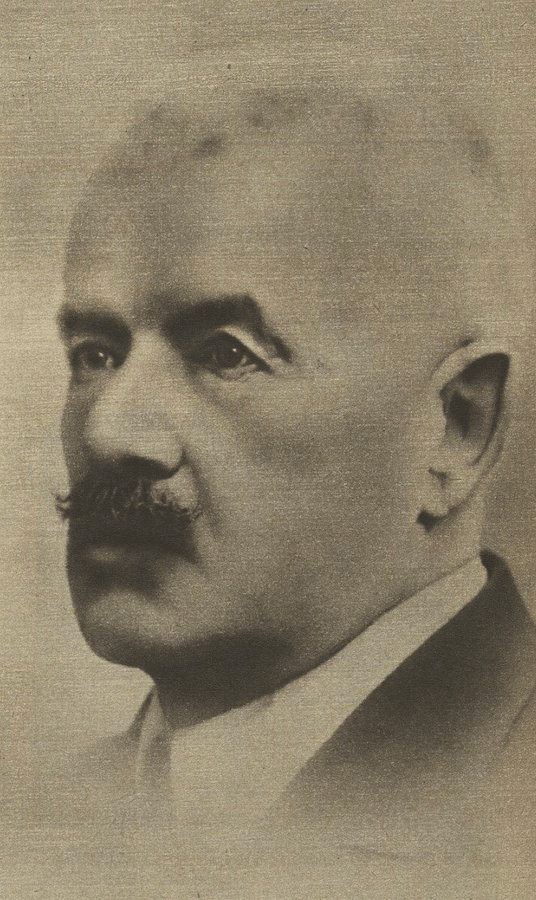

The Čapek brothers, meanwhile, were Josef (born 1887) and Karel (born 1890).

Josef moved to Prague in 1904, attending the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design (Vysoká škola uměleckoprůmyslová v Praze, VŠUP). He met his wife, Jarmila Pospíšilová (1889-1962), there.

After graduating, he attended the Académie Colarossi in Paris, returning to Prague in 1911 after less than a year to be with Jarmila.

Back in Prague, he joined the Mánes Association (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/01/18/prague-2-day-11-manesova/) and became co-editor of its magazine, Volné směry.

From 1912, he started to create Cubist paintings, with an increasingly playful, humorous touch as the years went by. He also dedicated himself to paintings for children.

Four of his works are below: Harmonikář (Harmonist) from 1913, Piják (Drunkard) from the same year, Letadlo (Aeroplane) from 1929 and Zpívající děvčata (Singing girls) from 1936.

Regarding journalism: In 1918, he became editor of Národní listy. He was fired in 1921, when that newspaper became increasingly nationalistic, and moved to Lidové noviny, where he would work as an editor and critic until 1939.

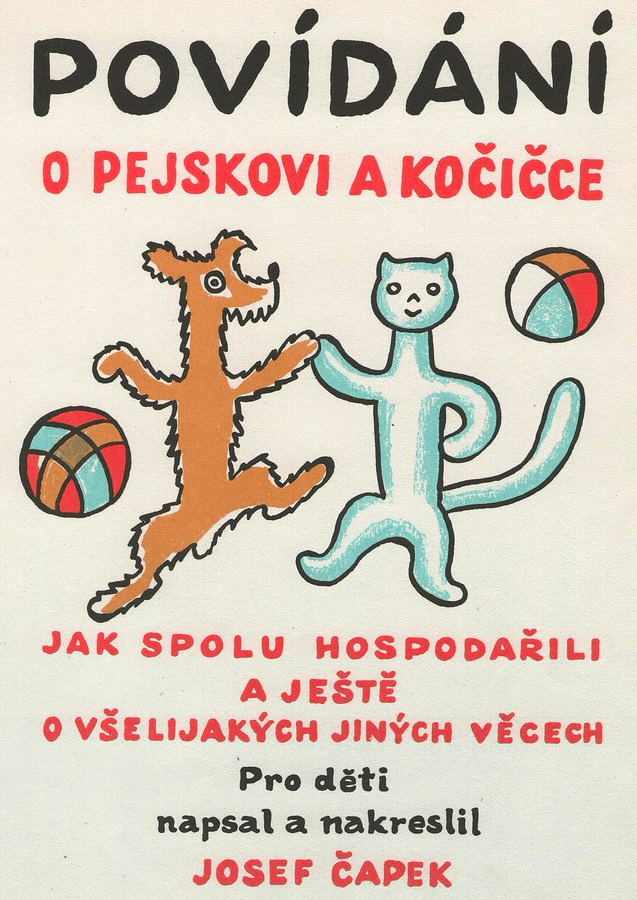

As a children’s writer, he wrote Povídání o pejskovi a kočičce (The Adventures of Puss and Pup) for his daughter, Alenka, in 1929. It’s a classic of Czech literature, and its cover is the dictionary definition of the word ‘charming’.

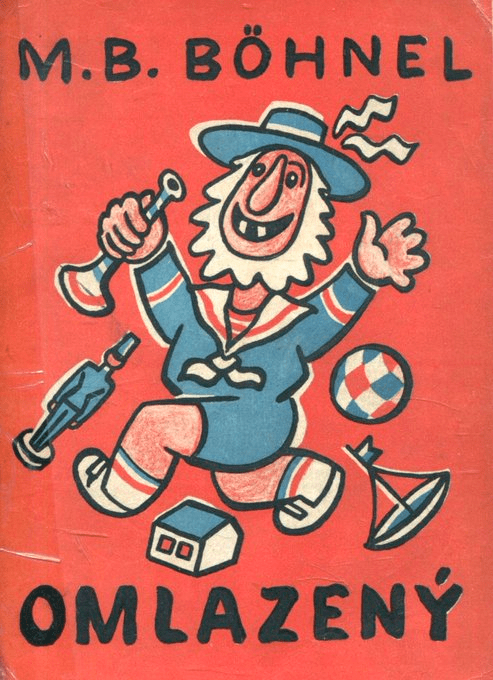

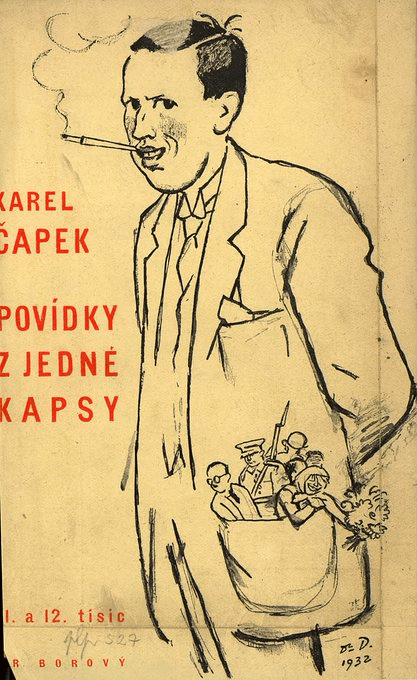

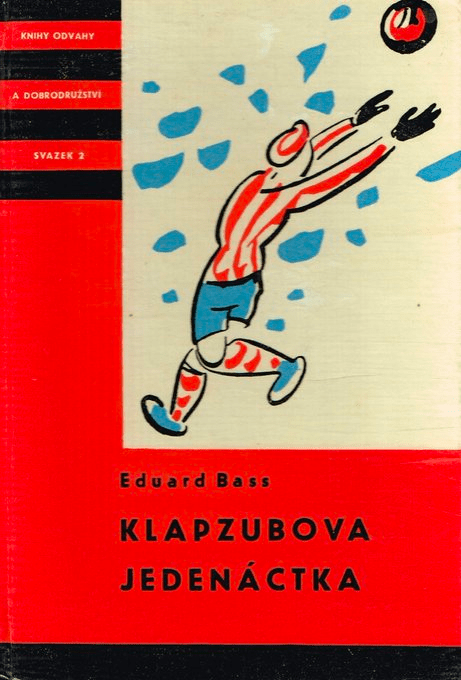

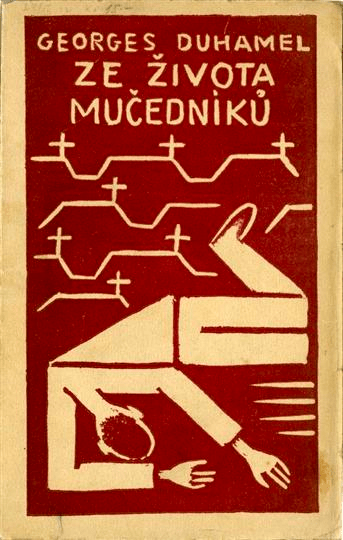

There is also a strong argument that Josef Čapek should have been allowed to design all book covers ever.

In the 1930s, Josef used his work to criticise Nazi Germany, and, on 1 September 1939, the day Germany invaded Poland, he was arrested.

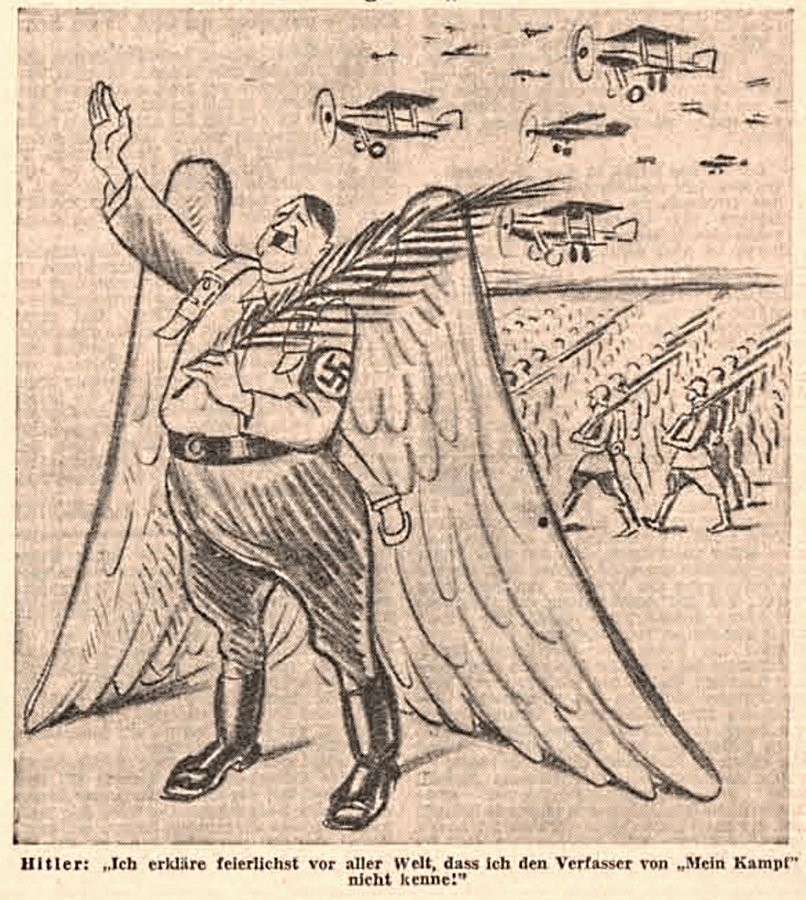

Here is a 1933 caricature: ‘I solemnly declare before the whole world that I do not know the author of ‘Mein Kampf’’.

Spending two and half weeks in Dachau, he was then moved to Buchenwald, where he spent two and a half years, and was forced to paint family trees of SS members.

In 1942, he was transferred to Sachsenhausen, and then, in 1945, to Bergen-Belsen, where he died of typhoid. The exact date of his death is unknown, as is his burial place.

A symbolic grave exists in Vyšehrad Cemetery.

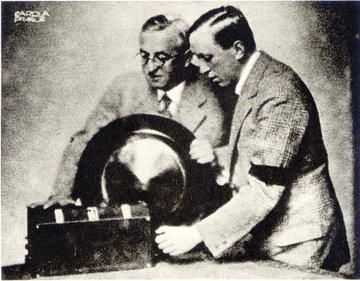

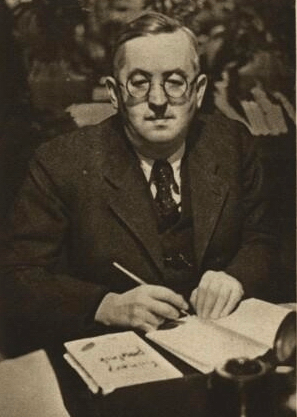

Karel, meanwhile, studied philosophy at Charles University. He graduated in 1915 and moved into journalism.

He wrote for Národní listy, moving on to Lidové noviny, along with his brother, in 1921, in protest at Josef’s dismissal from the former.

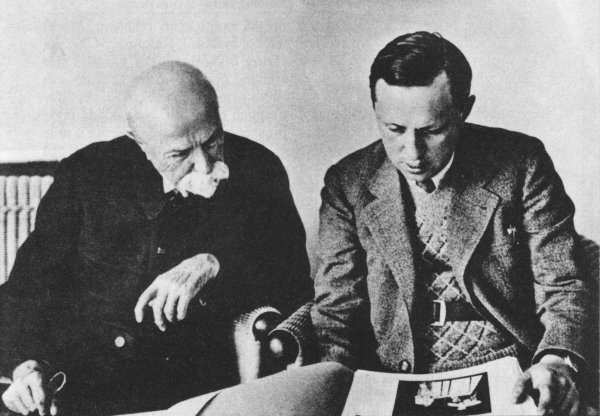

In these years, he became close to both Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk and his son Jan. Talks with TGM would later form the basis for the three-volume Talks with T. G. Masaryk (Hovory s T. G. Masarykem; 1928-1935).

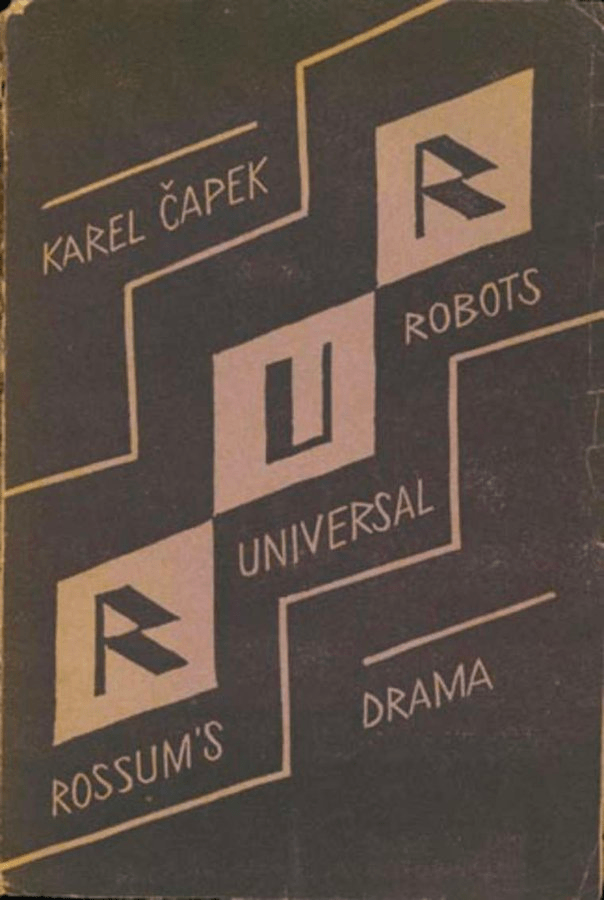

In 1920, he wrote R.U.R., a science-fiction play which introduced the word ‘robot’ to the world (it was Josef who came up with it). R.U.R. stands for Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti (Rossum’s Universal Robots).

(Cover designed by Josef)

Karel’s 1936 novel War with the Newts (Válka s Mloky) was another science-fiction work, dealing with a breed of newts that, after being enslaved, acquire human knowledge and start a rebellion.

A devoted anti-fascist, Karel became the Nazis’ most public nemesis in the Czech Lands after Beneš abdicated. He started to receive hate mail and malicious telephone calls.

Never in the best of health, he died of pneumonia on 25 December 1938, aged 48. The Nazi occupiers didn’t release he’d died until they came to his house to arrest him a few months later.

Karel’s wife, the actress Olga Scheinpflugová, survived the war and died in Prague in 1968. They are both buried in Vyšehrad Cemetery.

This thread barely touches the surface of Josef and Karel’s work.

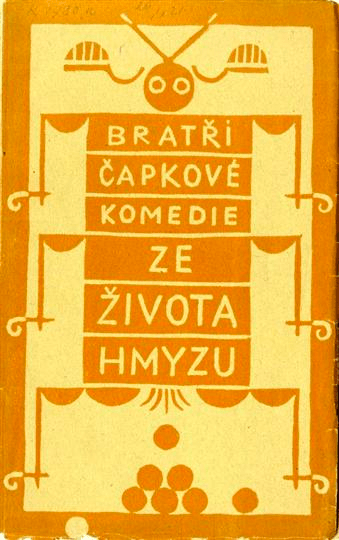

Their most well-known joint work is Pictures from the Insects’ Life / Ze života hmyzu (1921), in which a dream about insects acts as a a commentary on the people of Czechoslovakia in its earliest years.

There is also a memorial to them on Mirák which I’ll add some photos of when that square comes up in a couple of weeks.

Leave a comment