Originally published on Twitter on 1 December 2022.

Chodská was built in 1889.

From 1940 to 1945, this was Grimmova, after Jakob Grimm (1783-1863), co-author of the Deutsches Wörterbuch, co-editor of Grimms’ Fairy Tales, writer of Deutsche Mythologie and the elder of the Brothers Grimm.

Chodsko is a historical area in the Domažlice region, named after the Chodové, free peasants entrusted with walking along the forested border (chodit means ‘to walk’) and guarding it.

Chodové are at the front of this picture from Dalimil’s Chronicle, cutting down trees.

They had to ensure that the border did not change, that those travelling on the trade route to/from Furth im Wald in Bavaria could pass safely, and that enemies trying to enter through the Šumava would be pushed back.

The usefulness of their role meant that they were granted various privileges: they didn’t become serfs, were subject only to the king, and had their own self-government. The first privileges were granted in 1325, and the final one (there were 24 in all) in 1612.

However, the fact that these privileges were not written down proved to be to their disadvantage, and they were no longer enforced after Bílá Hora, with the Chodové becoming subject to labour duty like other peasants in the Czech Lands.

Direct pleas to Vienna didn’t help matters, and after the emperor rejected their demands in both 1692 and 1693, a full-scale uprising broke out.

This ended with the execution of its leader, Jan Kozina, in Plzeň in 1695.

In the 19th century, the Chodové became a symbol of national resistance, with Kozina being a figure in the works of both Alois Jirásek and Božena Němcová.

Here’s a painting by Václav Malý (1894-1935), ‘From a Pilgrimage to Chodsko’).

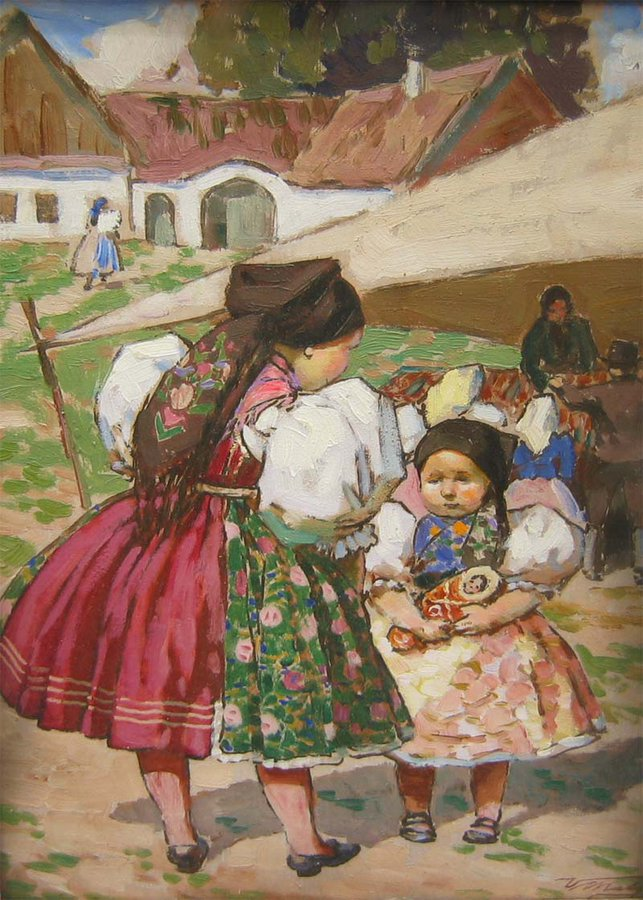

Painter Jaroslav Špillar (1869-1917) lived among the Chodové and used them as inspiration for his work. Here’s Chodové Family (1900) and Elderly Couple (1904).

While the Chod population has declined significantly – they are now present in eleven villages, and in the countryside – they maintain a strong individual culture, as well as their own dialect of Czech.

Features include an ‘h’ appearing before ‘u’ (už becomes huž), long vowels in possessive adjectives (náše, váších) and infinitives (čekát, zpívát), and k being used instead of g in loan words (telekram, rentken).

Also, families are referred to as -ouc rather than -ovi (Havlouc, Babišouc, Simpsonouc), and possessive forms don’t decline at all, irrespective of gender/case/number (if we spoke like this in Prague, I’d live in Žižkovo, and avoid ‘Karlovo most’ like the plague on weekends).

If you need proof that the internet is a wonderful thing when used correctly, these guys have a Teach Yourself Chod channel on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/c/K%C5%AFC%C3%AD16/videos

Finally, the Bohemian Shepherd is a Chodský pes in Czech, named after the dogs that the Chods used to help them in their guard duties.

They are gorgeous: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Chodsk%C3%BD_pes

Leave a comment