Originally published on Twitter on 22 December 2022.

Jana Masaryka was built in 1875.

Until 1884, this was Wimmerova, after Jakub Wimmer (1754-1822), entrepreneur, landowner, benefactor and colonel.

Then it was renamed Čelakovského after František Ladislav Čelakovský (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/02/18/prague-2-day-35-celakovskeho-sady/).

In 1926, the street was renamed Polská. Which means that I have to retract this tweet from a few weeks ago: https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/01/27/prague-2-day-14-polska/

(I still maintain that gritted Czech teeth must have been involved, though)

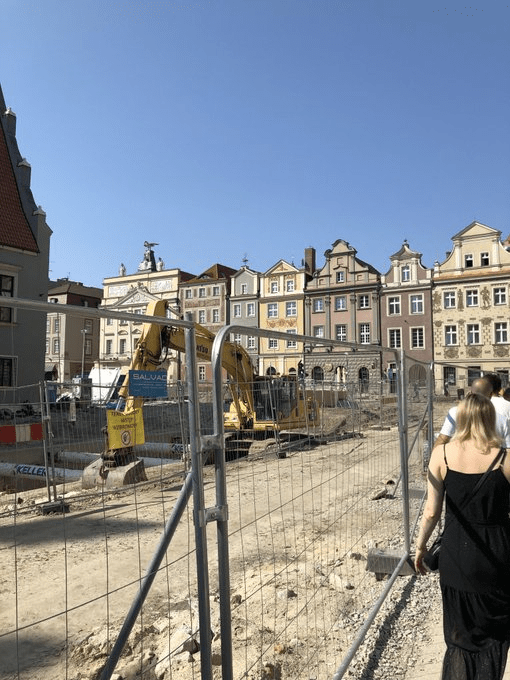

Things then got a bit more localised in 1940, when the street was renamed Poznaňská, Poznań having been annexed by Nazi Germany in 1939. Here are some snaps of when I chose the absolute worst time to try and be a tourist in Poznań this summer.

The street became Polská again in 1945, before becoming Jana Masaryka in 1946 (spoiler alert: during his lifetime).

However, from 1952 to 1990, it was Makarenkova, after Anton Makarenko (1888-1939), a Ukrainian who was the most influential educational theorist in the USSR (second spoiler alert: his death is quite murky too).

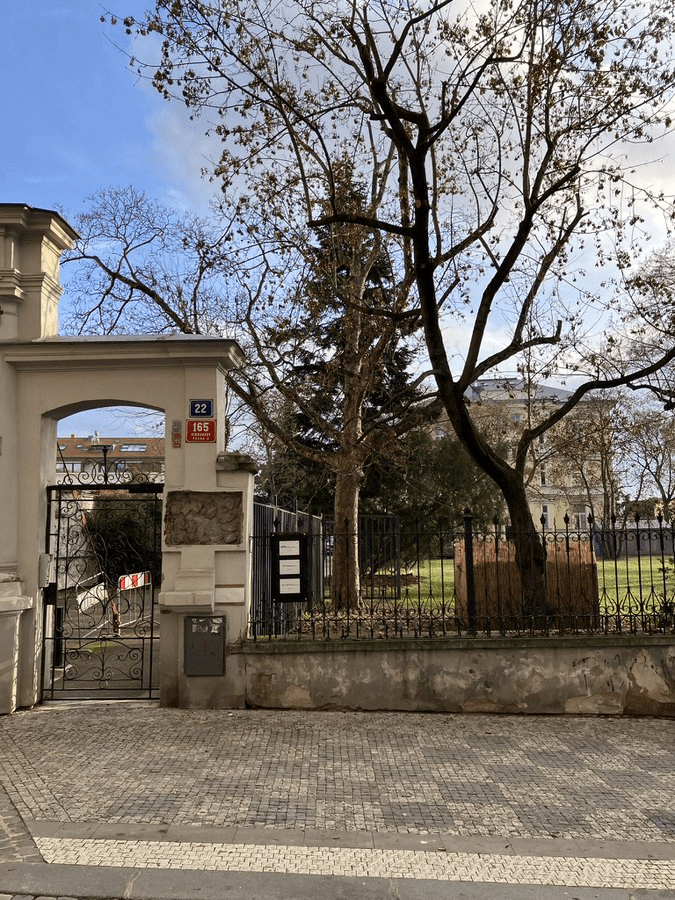

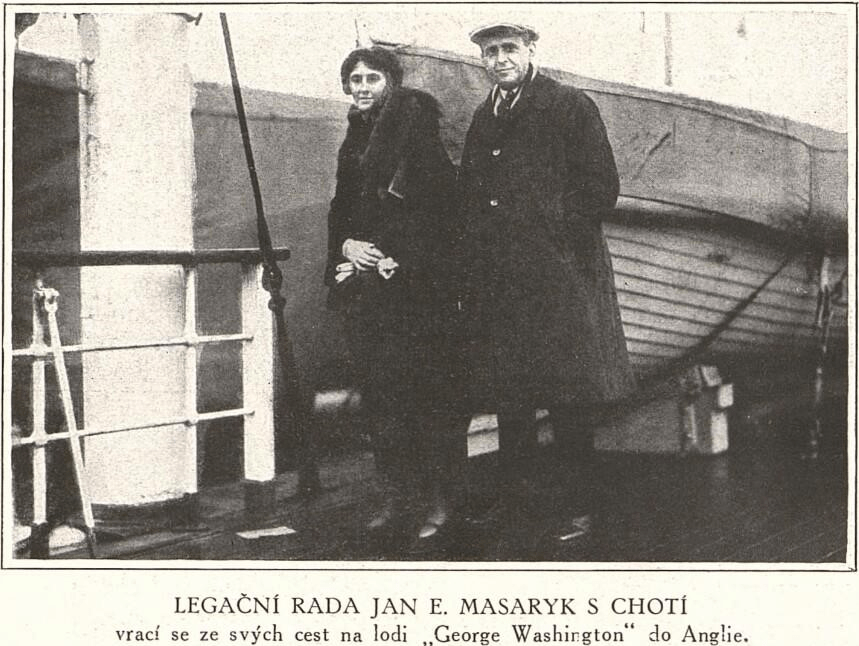

Jan Masaryk was born at number 22 on this very street in 1886. His parents were Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk and his American wife, Charlotte Garrigue.

He skipped his high school graduation and moved to the States in 1906, carrying out a series of low-paid jobs in New York and Bridgeport. He returned home in 1913.

During WW1, he fought on the Austro-Hungarian side in Galicia, Hungary and Italy.

While he received a silver medal for bravery, he was also bullied because of his father’s work in favour of Czechoslovak independence.

When dad became the first President of Czechoslovakia, Jan’s days of low-paid jobs were no more: he became chargé d’affaires in Washington in 1919, and, returning a year later, became personal secretary to Edvard Beneš, Minister of Foreign Affairs.

In 1925, he was sent to London as the Czechoslovak ambassador, where he would stay until late 1938.

In September of that year, he had personally handed a note, written by now-President Edvard Beneš, to Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, asking Britain to stop appeasing Nazi Germany. We know how that went.

After a brief stint in the US, Masaryk returned to London in 1940, becoming Foreign Minister of the Czechoslovak Government in Exile.

He also made regular contributions to BBC’s Czech-language programme, Volá Londýn (London Calling):

In 1945, after the war had ended, he signed the Charter of the United Nations on behalf of Czechoslovakia in San Francisco.

A year later, he became the first chairman of the World Federation of United Nations Associations (WFUNA).

Returning from exile in July 1945, he was Foreign Minister in three consecutive governments, and was also open to cooperation with the Soviet Union – which can presumably be explained, at least in part, by the aftertaste of his 1938 experience.

By 1947, Stalin had rejected Czechoslovakia’s proposed participation in the Marshall Plan, and Masaryk became disillusioned.

Yet when the communist coup (‘Victorious February’) occurred in 1948, Masaryk was one of the few non-communist government members who didn’t resign.

A month later, on 10 March, he was found dead under a window at his residence, Černín Palace.

The term ‘Third Defenestration of Prague’ is sometimes used to describe the incident – by those who think it actually was one.

It has never been clarified whether this was a murder, a suicide or an accident. An investigation in 1968 said it was likely to be the last of these, but didn’t rule out murder.

The picture above is taken from this footage of his funeral, which includes some wonderful images of Prague:

A 2021 investigation – the sixth – didn’t discount any of the three: https://www.novinky.cz/clanek/domaci-smrt-jana-masaryka-kriminaliste-v-dalsim-vysetrovani-neobjasnili-40353297

The 2016 film Masaryk (directed by Julius Ševčík, and renamed ‘A Prominent Patient’ for international release, as if ‘Masaryk’ were that damned unpronounceable) covered Masaryk’s life (in the UK) from 1937 to 1939. It won 12 awards at the Český lev.

Leave a comment