Originally published on X on 5 February 2023.

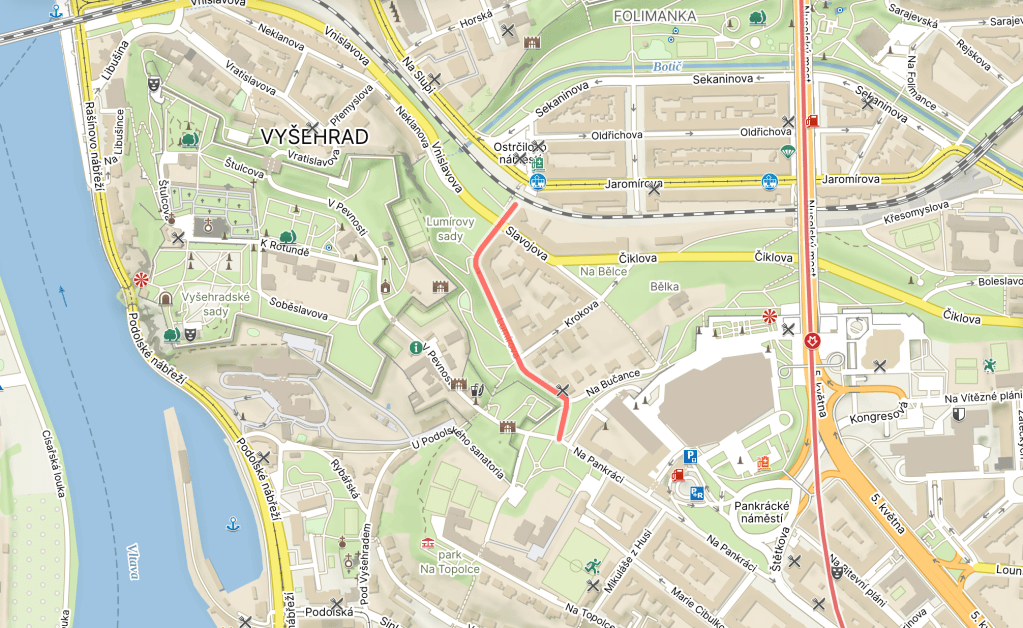

Lumírova was built before 1892.

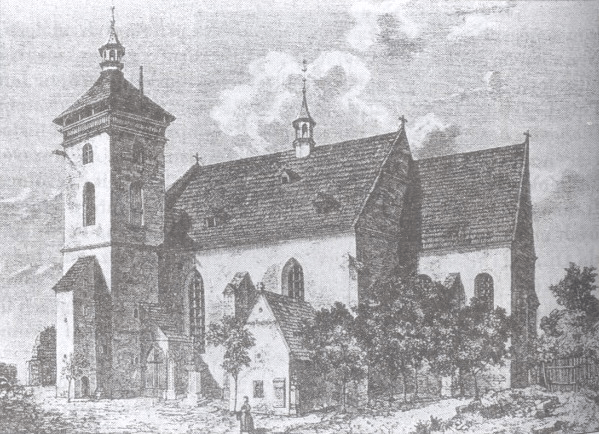

In 1817, a young lawyer called Václav Hanka allegedly went to Dvůr Králové nad Labem, and, while in the Church of Saint John the Baptist, found a manuscript from the 13th century (approx).

Given its place of discovery, it became known as the Rukopis královédvorský (RK).

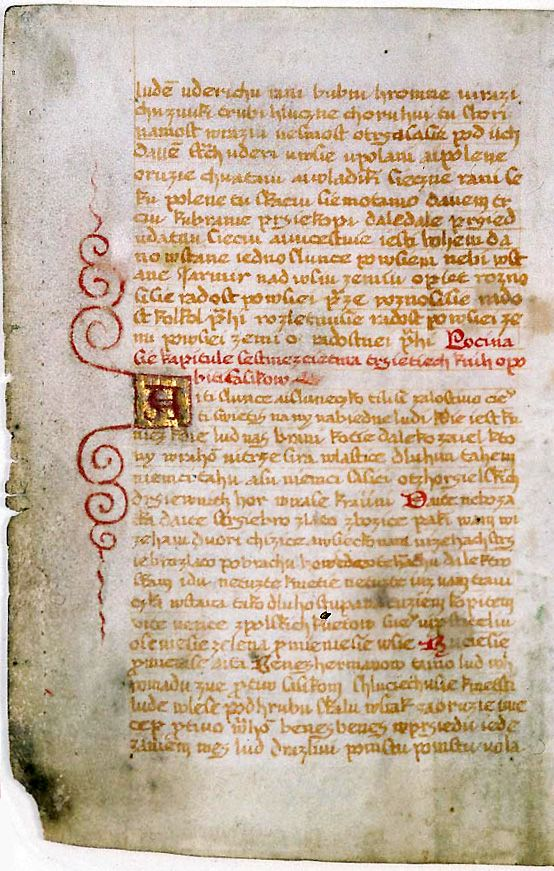

Hanka was granted ownership of the manuscript by the local authorities in 1818, and published it in 1819, complete with modern Czech and German translations.

The RK contained fourteen poems: six epics, six love poems, two lyric epics and a fragment of a larger poem, the remainder of which was missing.

One of the epics was called Záboj, about how Záboj and Slavoj had a victory over a German called Luděk.

One of the characters in the poem was a singer called Lumír, who sang beautifully enough for the people of Vyšehrad to get a bit emotional about it.

None of these individuals are mentioned elsewhere, but Lumír gave his name to the current street – part of which was called Zábojova until 1968.

Along with another manuscript, the supposedly 11th-century Rukopis zelenohorský, which was apparently also discovered in 1817 (but in Zelená Hora), it became popular enough to be published time and again. It even got translated into English.

An 1861 edition included cover art by a then-up-and-coming Josef Mánes (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/01/18/prague-2-day-11-manesova/).

And Lumír was clearly an impactful enough character to give his name to a literary magazine: https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/02/28/prague-2-day-37-mikovcova/

There was a bit of a problem, though. While some authorities, such as František Palacký, were convinced that the manuscripts were genuine, and were proof of the long, proud tradition of Czech literature, others, such as Josef Dobrovský, were not.

In 1886, a certain Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk became quite vocal about his belief that they were fake. Key Czech philologist Jan Gebauer also disputed their authenticity.

It all got rather heated, and Masaryk was accused of being anti-Czech, but voices suggesting that the manuscripts were authentic gradually died out.

In 1893, the Austrian Ministry for Education classified the manuscripts as ‘modern’ Czech literature (i.e. not ancient).

Between 1968 and 1971, Czech non-fiction writer Miroslav Ivanov headed a team at the Institute of Criminology, using forgery detection methods that hadn’t been available back in the 1880s.

They concluded that both manuscripts were palimpsests. In other words, old pieces of parchments had the original text scraped off them, and somebody wrote new text on there instead.

However, the Czech Manuscript Society, even now, wants to prove that the manuscripts were written in the 11th and 13th centuries, and not by the people who claimed to have randomly discovered them in 1817: https://www.rukopisy-rkz.cz/rkz/csr/

But none of this mess has stopped Lumír from getting his own statue at Vyšehrad, designed by Josef Václav Myslbek. You may recognise it, but here’s the original draft.

While both Lumír and Záboj also get statues at the National Theatre: https://www.theatre-architecture.eu/sk/db/?subjectId=64

Not bad going for a bunch of guys who were invented for a scam in the 1810s.

Leave a comment