Originally published on X on 4 March 2023.

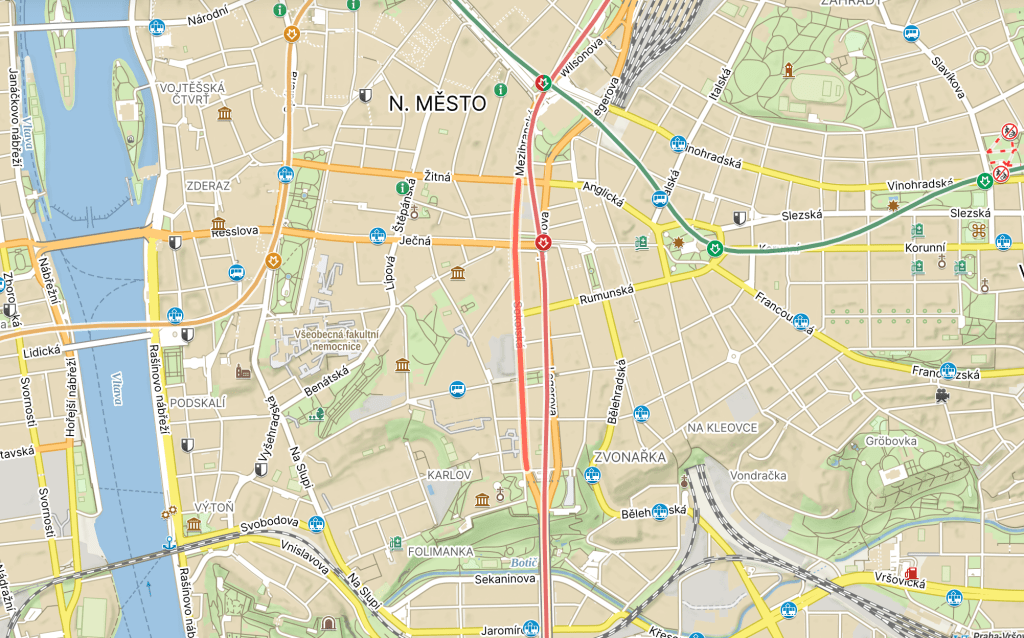

Until 1867, the street was called Horní Hradební, due to its location in the upper part of Novoměstské hradby, i.e. the New Town Walls.

From 1978 to 1990, the street was called Vítězný únor (Victorious February), after the Communist coup d’état of 21 to 25 February.

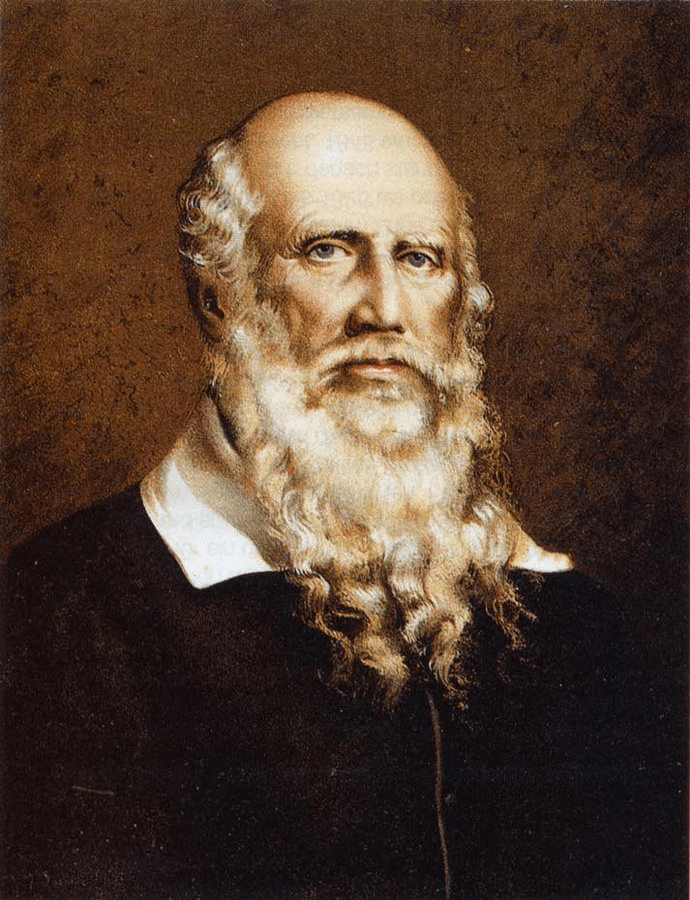

In 1816, Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, a Prussian gymnastics educator, wrote Die deutsche Turnkunst (‘The German Art of Gymnastics’).

His idea was that, if people participated in gymnastics associations, they would feel more confident, more patriotic and more inclined to fight for their fatherland (which, in his case, was obviously divided into several separate states at the time).

The idea caught on, including in Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia, as did the nickname of ‘Turnvater Jahn’ (which sounds like it should be followed by ‘and the Smurfs’ to me, but there you go).

In 1861, one Miroslav Tyrš, while in discussions about the formation of a German-Czech gymnastics club, got annoyed at a potential backer saying they would only finance it if it were to be a German organisation.

Therefore, in 1862, the two groups formed their own associations: the Deutscher Prager Turnverein and the Prager Turnverein (auf Deutsch but distinctly tschechisch). It seems that the two groupings continued to maintain good relations, though.

Two years later, the latter became known as ‘Pražská tělocvičná jednota Sokol’ (Prague Gym Union Sokol), a sokol being a falcon. From 1870, members would also be known as sokolové.

Tyrš (who we’ll learn more about when we get to his street) became vice-president, while the president was Jindřich Fügner (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/07/06/prague-2-day-58-fugnerovo-namesti/).

Other founders and committee members included influential promoters of the Czech cause such as Count Rudolf Thurn-Taxis, and brothers Julius and Eduard Grégr, co-founders of the Young Czech Party.

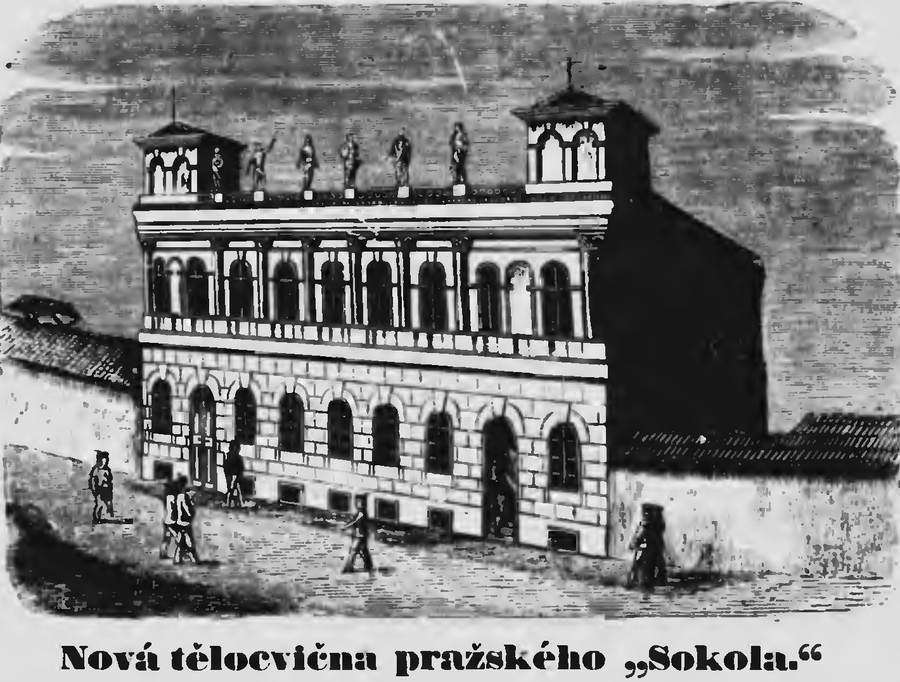

In 1863, Fügner purchased a plot of land on what is now Sokolská; a gymnasium was opened here in December 1863, at number 1437.

By 1865, Sokol associations had almost 2,000 members; the following year, following the Austro-Prussian War, Tyrš managed to add military training to their activities.

In 1868, firefighting activities were added to the list of activities, although this was discontinued in 1882.

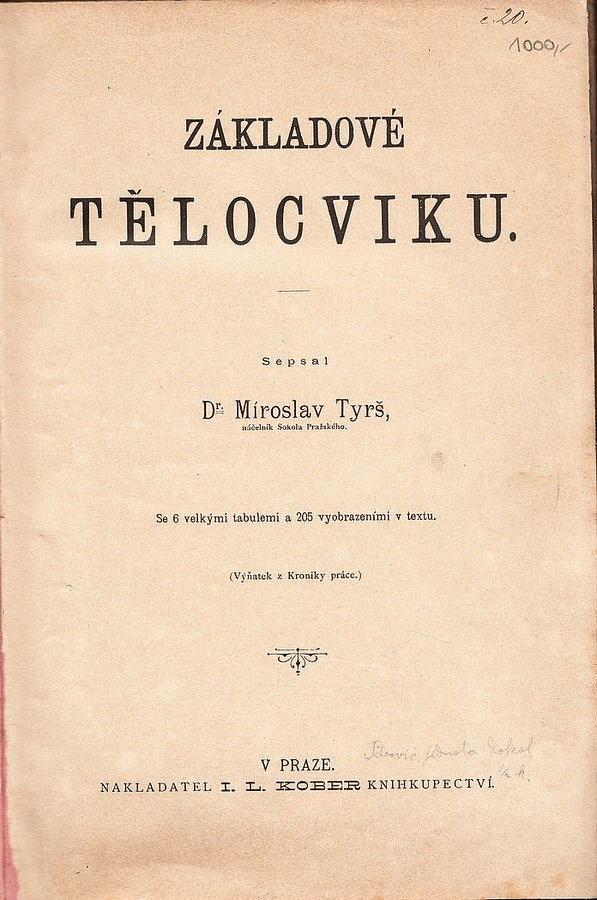

In 1873, Tyrš published Základové tělocviku (The Basics of Gymnastics), which set out the Sokol system – and determined Czech names for the exercises practised.

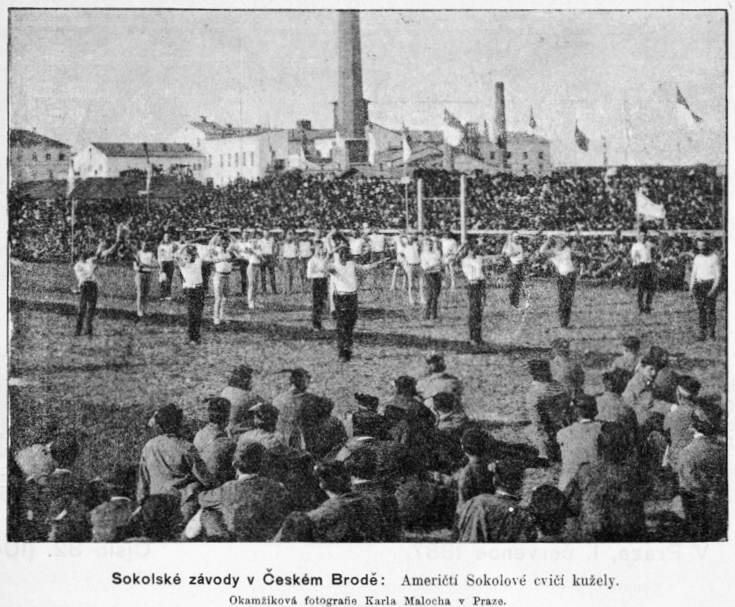

In 1882, the Sokols held their first slet (mass games – a slet is a flock of birds) on Střelecký ostrov. A further five would be held before the outbreak of WW1 (the pic is from the 1887 edition).

The decade would also see the Prague Sokol going to Paris to take part in the French Physical Education Festival in 1898, which definitely gained the attention of the Habsburgs – but also of French politicians, with whom the Czechs would start to set up useful alliances.

Multiple visits to other key locations ensued, including Ljubljana (1888 and 1904), L’viv (1892 and 1903), Wrocław (1894), Hamburg (1898), Nuremberg (1903), Frankfurt (1908) and Leipzig (1913).

Sokols started to be founded elsewhere: for example in Sofia (1879), Belgrade (1891), Berlin (1893), Tbilisi (1898) and London (1903). The United States also had 13 Sokol associations by 1878.

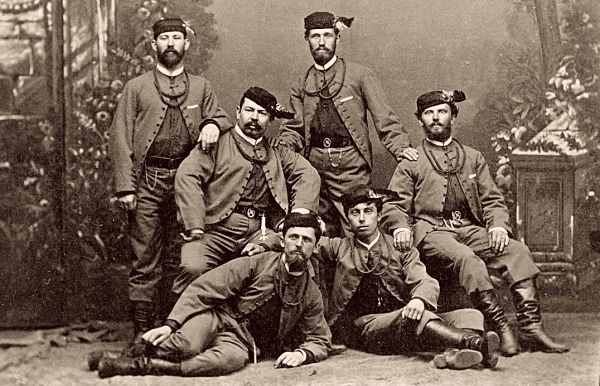

The picture below is of a Serbian Sokol unit in Herceg Novi, now Montenegro.

Meanwhile, slets held in the 1900s would have an increasingly pro-Slavic focus, with the 1912 edition even being named the Všeslovanský (Pan-Slavic) slet.

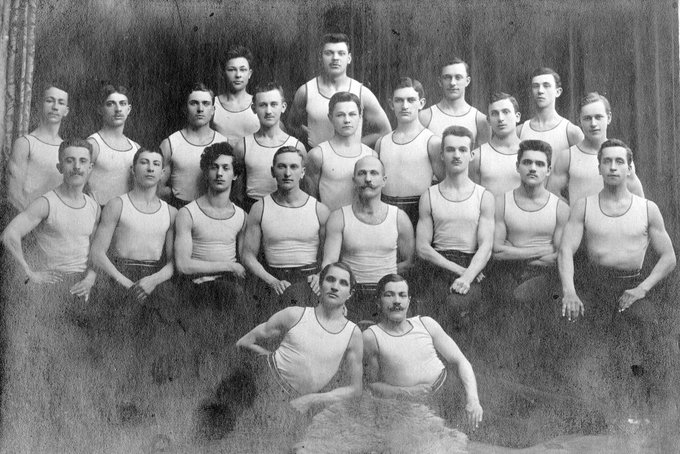

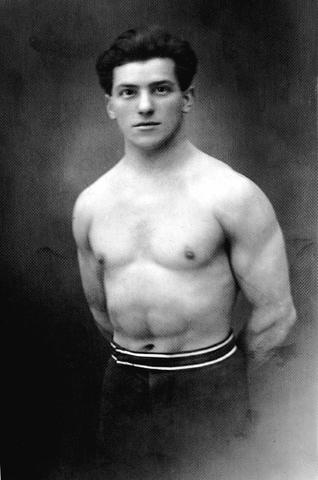

(pics not specifically of slets, but included because they’re great pics)

While the Sokols were officially disbanded in 1915, their members played a key role in the Czechoslovak Legion in World War One, for example forming part of the military group Nazdar, which became part of the French (Moroccan) Foreign Legion.

After WW1 – and after its members helped to defend the Czechoslovak border with Poland in 1919 – the association became bigger than ever. Sokolovny became proper cultural centres, including restaurants, cinemas and theatres.

Sokol became a member of the Czechoslovak Olympic Committee in 1919, and the Sokol team participated in the Olympics in Antwerp – the first to include a Czechoslovak team – in 1920. In Paris 1924, they would win nine medals.

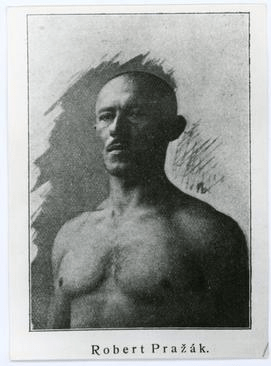

Pics are of Sokol members Bedřich Šupčík (gold medal in rope-climbing, 1924), Ladislav Vácha (bronze medal in rope climbing and rings, 1924; gold medal in parallel bars, 1928) and Robert Pražák (three silver medals in gymnastics, 1924).

Inevitably, after 1938, the movement was suppressed by the Nazis. Gymnasiums were banned in October 1939, and the movement’s activities were banned entirely in April 1941.

In October of the same year, Operation Sokol involved the arrest of 1,500 Sokols, many of whom were sent to Terezín and Auschwitz. The Nazis collected all the association’s membership fees and equipment for themselves.

After the Prague Uprising – in which over 500 of its members died – Sokol was revived (pic is from the 1948 slet), but the Communists ultimately suppressed the free-thinking organisation in favour of the Czechoslovak Union of Physical Education and, of course, Spartakiády.

The organisation would not be revived again until 1990. There are now about 180,000 members, and the next slet, if you’re interested, will be happening in 2024: https://sokol.eu/projekt/slet

Such a broad topic, this. So much that I’ve had to miss out before this thread takes up the entire internet. Feel free to add your own thoughts and anecdotes below!

Leave a comment