Originally published on X on 4 April 2023.

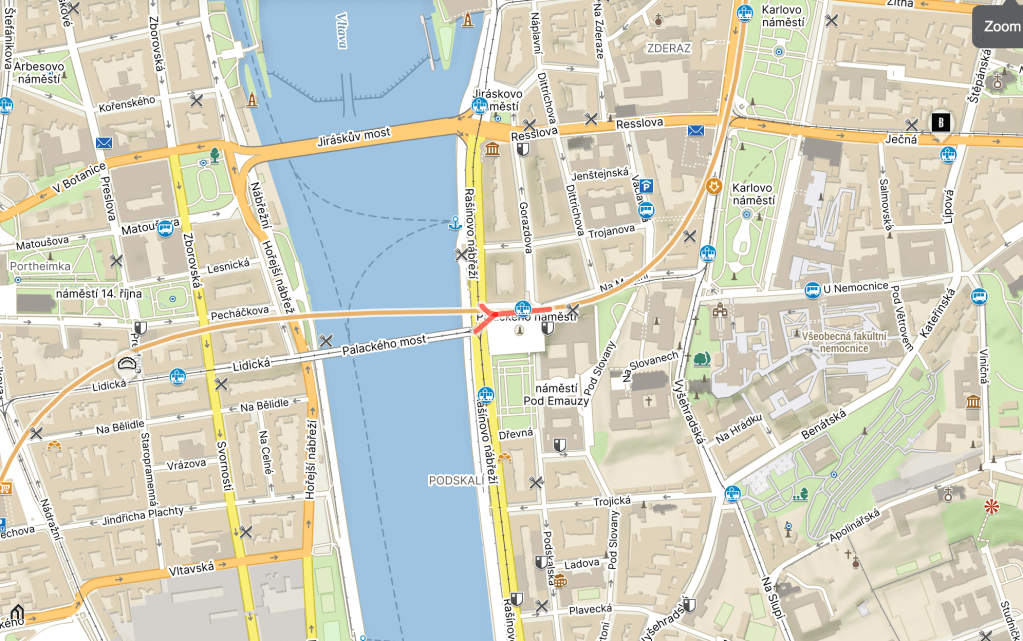

Palackého náměstí was created in 1896 as a result of renovation of the nearby embankment.

From 1942 to 1945, this was Rudolfovo náměstí, after Rudolph II (1552-1612), the Habsburg who certainly made Prague a more fascinating cultural centre than ever, but whose actions also indirectly led to the Thirty Years’ War.

František Palacký was born to a Protestant family in Hodslavice, Eastern Moravia, in 1798. He was educated in Kunvald/Kunín, Trenčín and Pressburg (now Bratislava), where he befriended one Pavol Jozef Šafárik (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/07/06/prague-2-day-61-safarikova/).

After a stint as a tutor to noble Hungarian families, during which he decided to devote himself to the study of Czech history, he settled in Prague in 1823, helped by his budding friendship with one Josef Dobrovský.

In 1825, Palacký became the first editor of Časopis Českého muzea, the magazine of the Czech Museum. From 1830, he was also a member of the Museum’s committee.

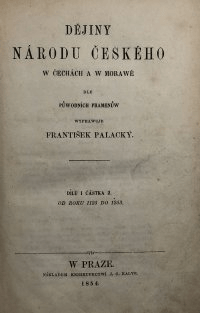

The period would also see Palacký being invited to produce a history of the Czech nation (up until the Habsburg period started in 1526) – the first volume of Dějiny národu českého v Čechách a v Moravě would appear in 1836, and the last in 1867.

Inevitably, a pro-Hussite, pro-Bohemian work, written by a Protestant, caught the Austrian authorities’ eye, and the pre-1848 editions were subject to police censorship.

When things got a bit revolutionary in 1848, Palacký took a more cautious approach than the St Wenceslas Committee (coming up in a few days), insisting that the Czech national movement should act according to the law.

However, in April 1848, he wrote the famous Psaní do Frankfurtu (Letter to Frankfurt), explaining why the Czechs could not join a unified German parliament, and, two months later, headed the First Slavic Conference. His days in the back seat of the movement were clearly over.

Sitting in the Reichstag when it was moved to Kroměříž (1848-9), he supported the continued existence of Austria, but as a federation of regions with equal rights. He even drafted a constitution to this end. Of course, Franz Joseph I and his taste for centralism prevailed.

Having spent the 1850s dealing more with history than politics, Palacký was invited to the Austrian senate by Franz Joseph in 1861, but basically stopped turning up almost instantly when he realised he wasn’t going to be able to achieve anything there.

He was also a member of the Bohemian Diet from 1861 to 1875; he came under fire from the more radical Young Czechs for his (relative) support for Austria – support which evaporated somewhat in 1867 with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise.

In 1868, it was Palacký who tapped the inaugural stone of the National Theatre; with this and other appearances at pro-Czech events, he soon became known as the ‘Father of the Nation’.

Palacký died in Prague in 1876, and his funeral was attended by tens of thousands of people. He’s buried in Lobkovice.

Palacký is also in the ‘you might have seen his face today’ category, although you may not have noticed, as you were, like I often do, wondering why the bankomat couldn’t just give you 5 x 200 Kč like you wanted.

He also knew Czech, German, Latin, Old Slavic, Hungarian, Russian, English, French, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese. A man after my own heart.

Leave a comment