Originally published on X on 29 January 2024.

When the New Town was founded, this street was named Angelova, after Angelo of Florence (died 1408), court apothecary under Charles IV and his son, Wenceslas IV.

In 1757, it was renamed Bredovská after the noble Bredow family (Josef Breda was the governor of Prague’s Old Town, and owned property here).

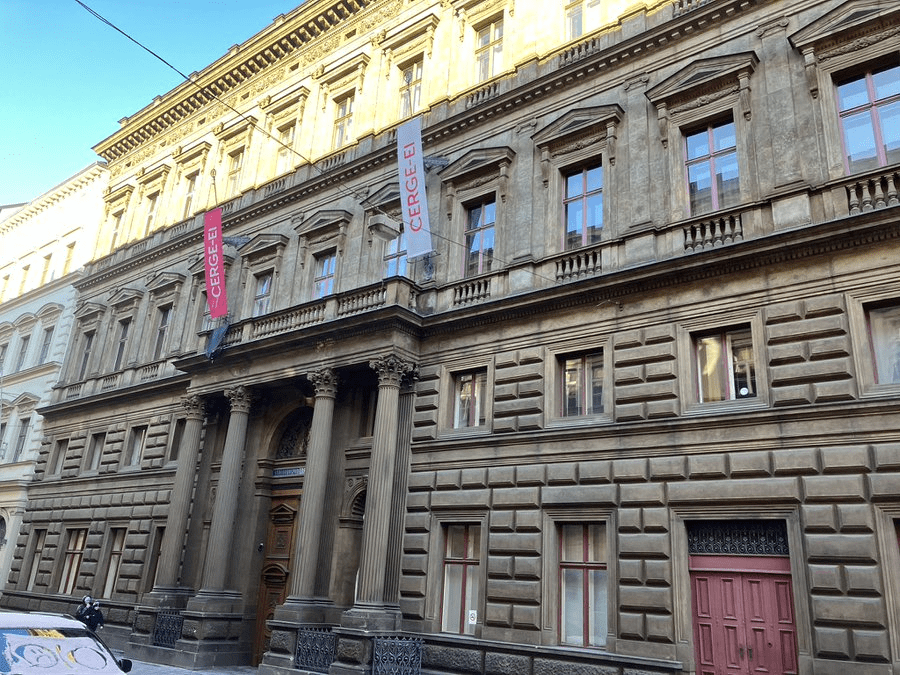

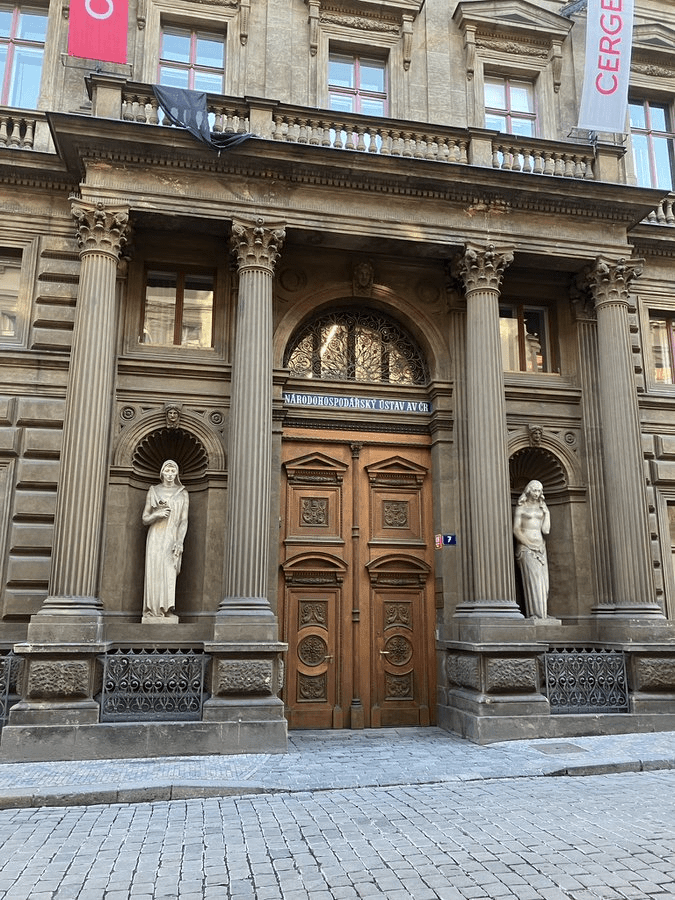

One such property was turned into an orphanage upon the order of Maria Theresa; it’s now known as Schebek Palace, as a businessman called Jan Schebek commissioned a Neo-Renaissance makeover in 1870.

It’s now the headquarters of the National Economic Institute of the Academy of Sciences.

Another palace in the street – Petschek Palace – was commissioned by a local, German-speaking banker, Julius Petschek (1856-1932), as the headquarters for the family-run bank, Bankhaus Petschek & Co.

The Petschek family were Jewish, and the heads of the bank after Julius’ death – his son Walter and his nephew Hans – migrated in 1938, later settling in the United States.

In March 1939, the Nazis proclaimed the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; a few months later, the Gestapo started to use Petschek Palace as their headquarters. They used the premises to torture and interrogate members of the Czech resistance.

About 36,000 people were interrogated here; many of them did not survive; the building became known colloquially as ‘Pečkárna’ (possibly a pun on the Petscheks, also similar to the Czech word for ‘bakery’). A plaque outside commemorates the brutality of the Gestapo.

The street therefore got its current name in 1946, but what isn’t mentioned on the plaque is the fact that, by this point, it was the home of the Czechoslovak secret police, also notorious for their brutal treatment of suspects.

They moved to new headquarters in 1948, since which point the building has been used by the Ministry for Industry and Trade.

There’s a museum, including a replica of the Gestapo torture chamber; visits are by request only. It’s run by the Czech Union of Freedom Fighters, a veteran organisation which isn’t without controversy, as several members served in the security services prior to 1989.

You may also recognise the building’s exterior from this scene in The Bourne Identity, where it was a body double for the Gemeinschaft Bank in Zürich.

Next to Schebek Palace, and built around the same time as it, number 9 is the former Buštěhradská dráhy headquarters, named after the railway company it was built for. It’s now the seat of the Czech Communist Party.

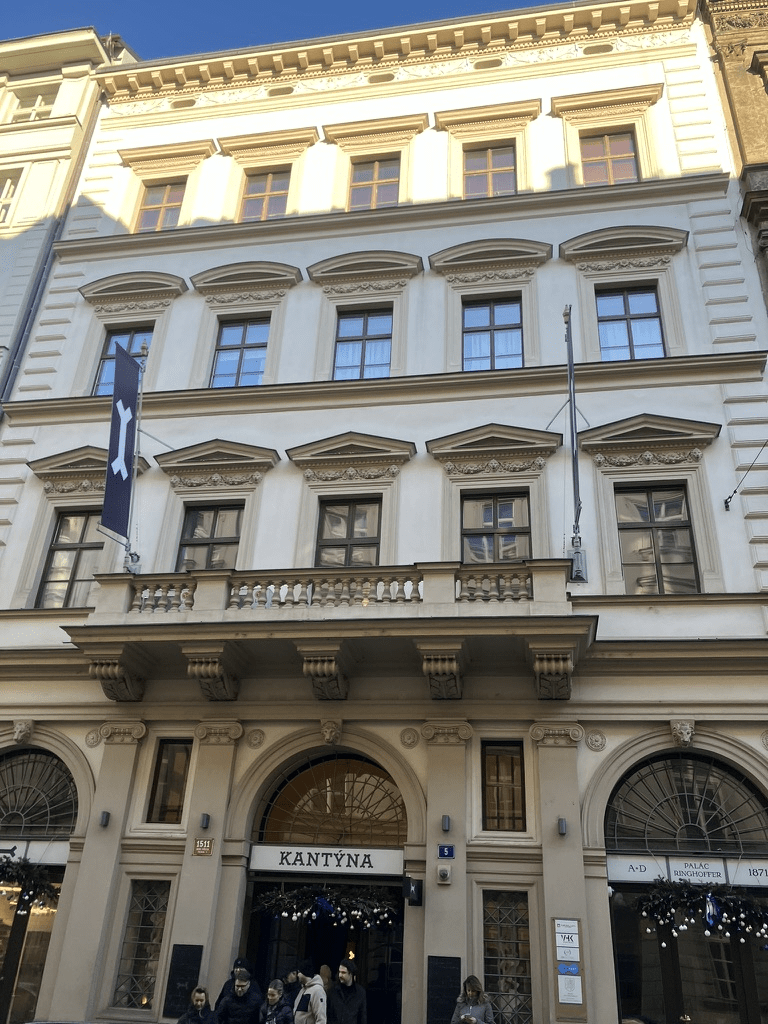

On the other side of Schebek Palace, Ringhoffer Palace has formerly been the headquarters of banks, but now hosts Kantýna, a popular restaurant.

Across the road, you can get a glimpse of what Prague’s main post office looks like from the other side.

And I can think of some people who will definitely not be happy if I fail to mention that number 13 in the street is the Prague branch of the British Council.

Finally, Ukrainophiles will find this plaque dedicated to Taras Shevchenko on the corner with Opletalova interesting.

There was a printing house here; in 1876, this is where the first uncensored edition of his 1840 collection of poems, Kobzar, was published. The publisher was Eduard Grégr, of the Young Czech party.

Sadly, Shevchenko never got to see this edition, having died fifteen years earlier. You can see pictures of this edition here: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%D0%9A%D0%BE%D0%B1%D0%B7%D0%B0%D1%80%D1%8C_(1876).djvu

Leave a comment