Published on X on 2 and 3 April 2024 (there was a fair amount to say).

Part 1: the history

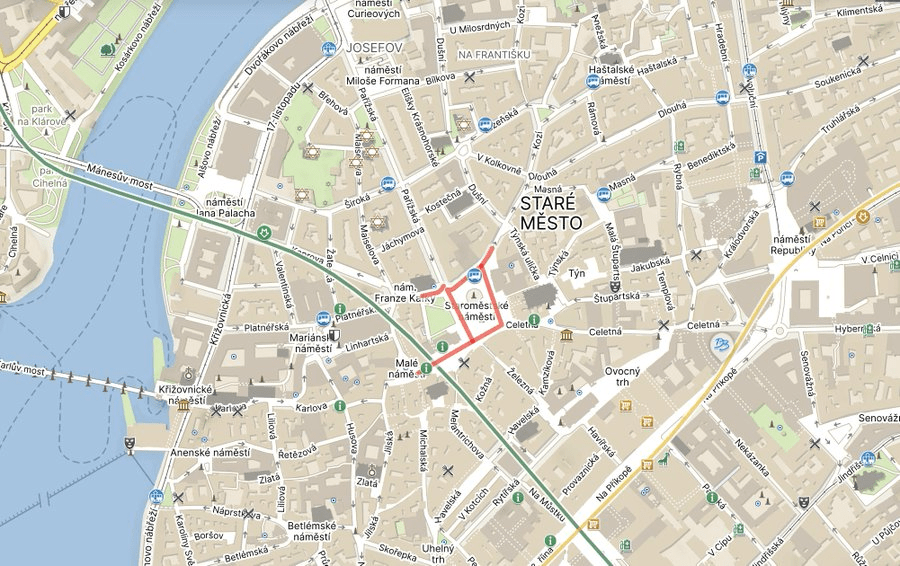

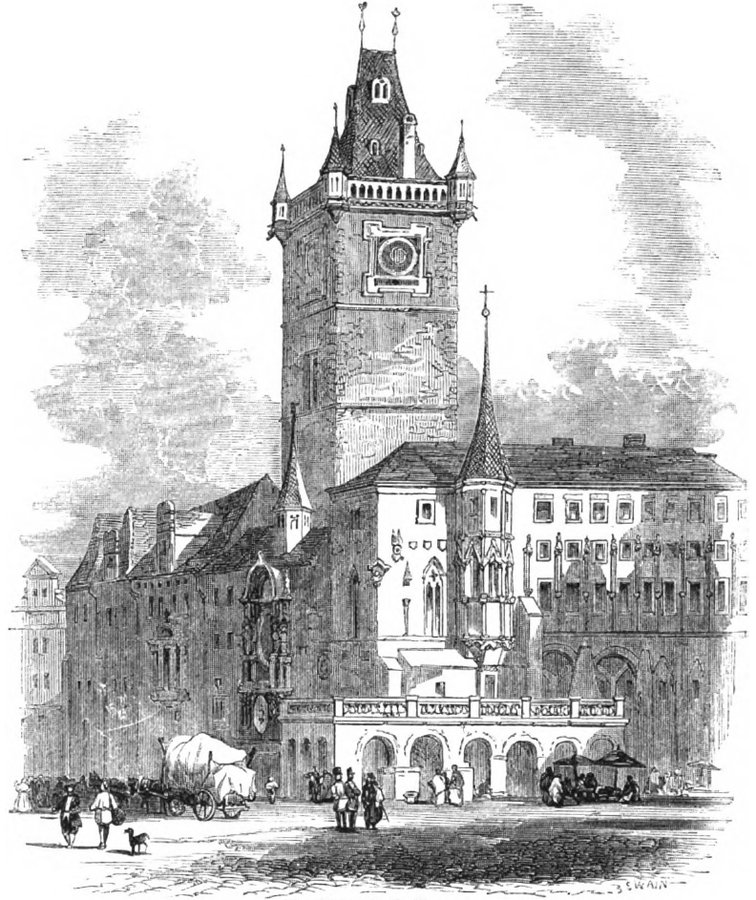

In 1338, John of Luxembourg (King of Bohemia from 1310 to 1346) gave the Old Town permission to build itself a town hall. This seemed like the perfect location, as a major market had existed here for centuries (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/10/12/prague-1-day-189-tynska/).

Rather than build something from scratch, the councillors decided to buy property from rich families and adapt it.

By 1364, the Town Hall had a tower – Prague’s tallest at the time, and not significantly changed in the centuries since.

As a result, the square was called Staré tržiště (The Old Marketplace), which changed to Staroměstský rynk (Old Town Market) in the 14th century (note how ‘rynek’ is still the standard Polish word for ‘market square’, and Poland has a lot of fine ones).

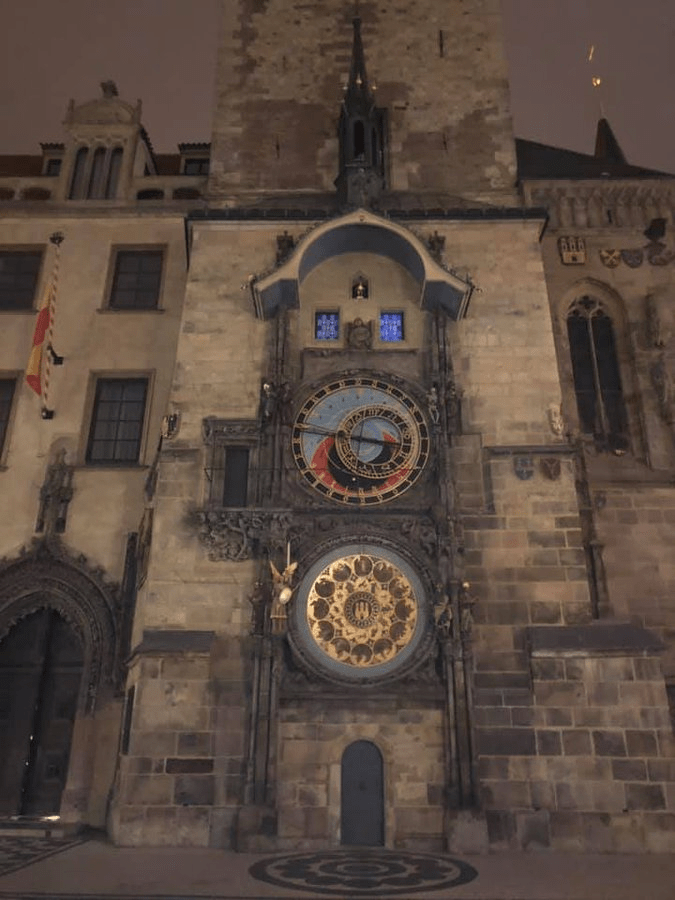

In 1410, an astronomical clock, largely the work of Mikuláš of Kadaň and Jan Šindel, was inaugurated. It’s the oldest clock of its kind that’s still in operation.

Its current decorations are from 1490 (possibly carried out by Jan Růže), and the clock was worked on by Jan Táborský of Klokotská Hora in the mid-16th century. It’s not changed fundamentally since (the crowds have increased, though).

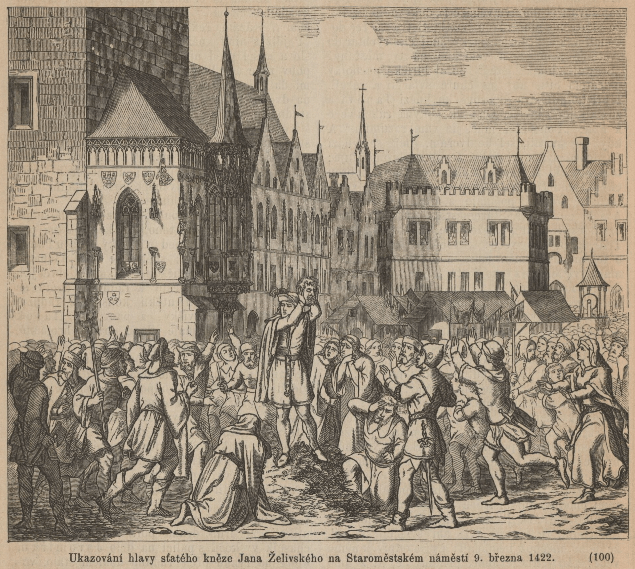

In 1422, not long after the clock came into existence, Old Town Square saw one of its most infamous events, when Jan Želivský (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2022/11/19/prague-3-day-23-jana-zelivskeho/) was arrested by the Prague town council and then beheaded here.

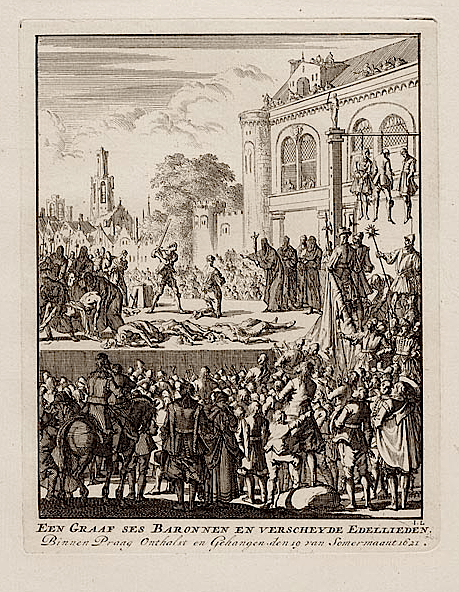

But that was outdone in gruesomeness 199 years, later, when the Habsburg regime executed 27 Czechs who had led the Bohemian Revolt, which had been quashed by the Czech defeat at the Battle of White Mountain (Bílá Hora) the year before: https://english.radio.cz/400-years-pragues-old-town-square-executions-8720953.

In 1650, Old Town Square gained the Marian Column, which was Ferdinand III’s way of saying thanks to Prague for defeating the Swedes in 1648.

One might say that not forcing people to convert to Catholicism is another good way of showing gratitude, but hey.

The first picture shows it as it looked around 1900; the second shows it as it looked in 1918, when it was pulled down by a group of Žižkov firemen, encouraged by Franta Sauer (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2022/11/22/prague-3-day-76-sauerova/).

It was then restored in 2020, supported by ODS and ANO among others, but not so much by people like Mayor Zdeněk Hřib who (like me) don’t exactly see it as a symbol of tolerance, religious freedom or independence: https://english.radio.cz/marian-column-returns-old-town-square-after-more-a-century-8682622.

By the 17th century, the square had come to be known as ‘Staroměstský plac’ (Old Town Market) or ‘Velké náměstí’ (Big Square).

In 1784, when the Old Town, New Town, Malá Strana and Hradčany became one administrative unit, the town halls of the last three were closed down, and the one on Old Town Square started to serve the whole of Prague.

Key events in the 19th century included the Neo-Gothic extension of the Old Town Hall (1838-1848), the official introduction of Staroměstské náměstí as the square’s name (1895), and – hard to imagine now – the introduction of trams. They would run until 1966.

Here’s a picture of one going past the Astronomical Clock, an image so unimaginable that I’m half-expecting to find out it’s made by AI.

At the start of the 20th century, Old Town Square wasn’t immune to the ‘rehabilitation’ (asanace) that aimed to improve hygiene but also destroyed a lot of cultural heritage.

One victim was the Krenn House, one of the largest Baroque houses in the Old Town.

Old Town Square has always been a popular place for demonstrations – this picture is of a demonstration in support of universal suffrage, held in November 1905.

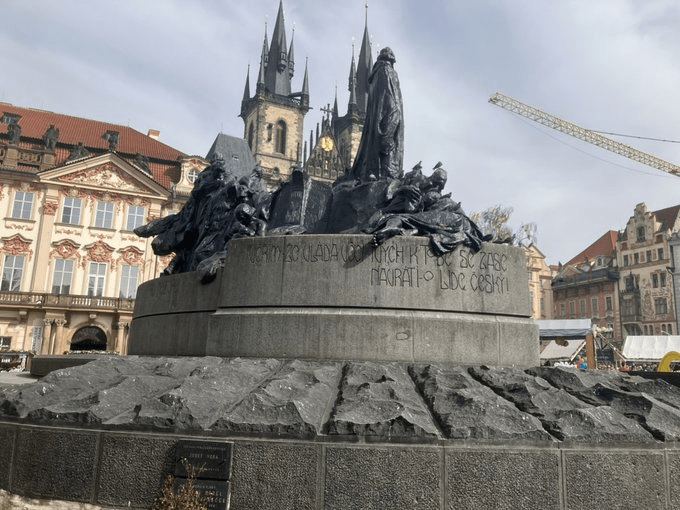

In 1915, a monument was erected to Jan Hus, 500 years after he was executed. Financed by public donations, it soon became a symbol of resistance to Habsburg rule.

This therefore made it an inevitable location for pro-independence demonstrations in 1918 (the speakers in this two pictures are the politician, Václav Klofáč, and the lawyer and soon-to-be Inspector General of Czechoslovakia’s armed forces, Josef Scheiner).

During the Prague Uprising in May 1945, the Town Hall was captured by insurgents and became one of the main targets of Nazi fighters, who set the building on fire, destroying part of the city archives. The Neo-Gothic extension had to be demolished: https://www.esbirky.cz/predmet/150989?searchParams=.

In November 1962, a bomb went off on Old Town Square during a celebration of the Great October Socialist Revolution.

29 people were injured; the Communist media didn’t devote a single word to the incident, and the case remains unsolved: https://cesky.radio.cz/vybuch-na-staromestskem-namesti-v-roce-1962-se-vysetrit-nikdy-nepodarilo-8767167.

Also unsolved is the story of a pipe bomb which exploded at the foot of the Jan Hus statue in June 1990, injuring 18.

This is how it was reported by the LA Times at the time: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-06-03-mn-803-story.html.

And footage from the TV news: https://ct24.ceskatelevize.cz/clanek/specialy/30-let-zpet-vybuch-na-staromestskem-namesti-49018.

Another bomb would go off at Hostivař a couple of month later, made from the same piece of pipe: https://ct24.ceskatelevize.cz/clanek/specialy/30-let-zpet-hostivarska-bomba-47510.

You may also want to take a look at https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/29/prague-1-day-155-krocinova/ to learn about a fountain which isn’t on the square anymore.

Part 2: the buildings

Mikšův dům once belonged to a furrier by the name of Mikeš, but (after a fire) was bought by the Old Town in 1458 and incorporated into the Town Hall.

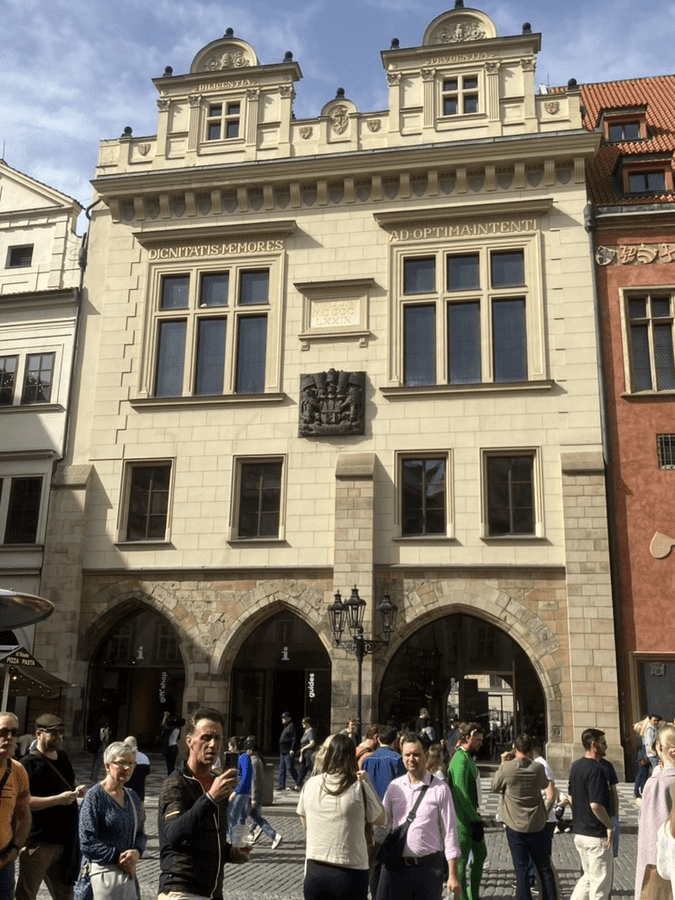

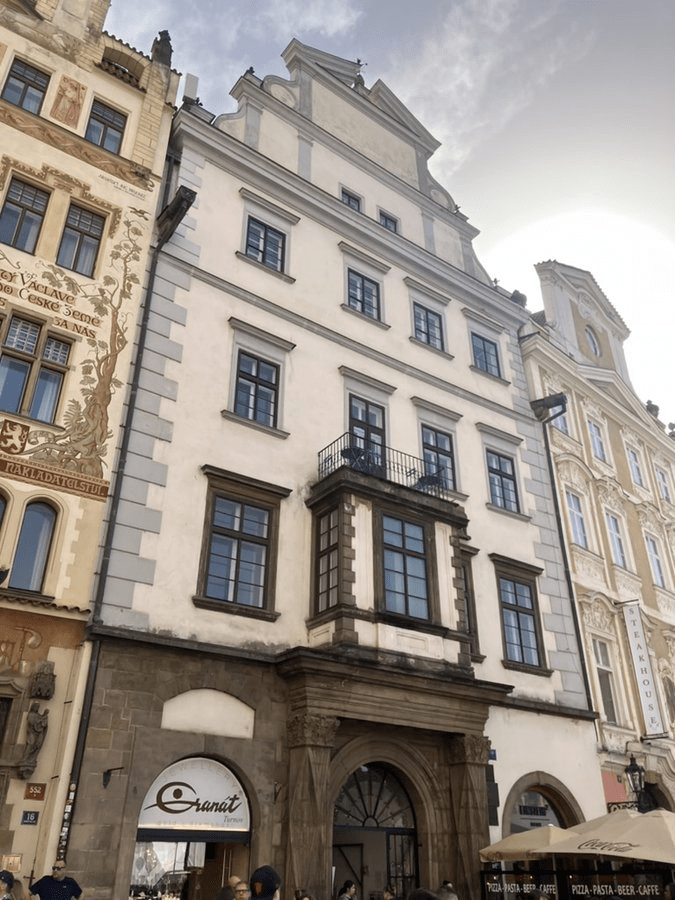

Next door, Dům kramáře Kříže, has a very similar story – Kříž was a shopkeeper who bought the house in 1387, and it too became part of the Town Hall in 1458. It includes council chambers, one of which is used for weddings.

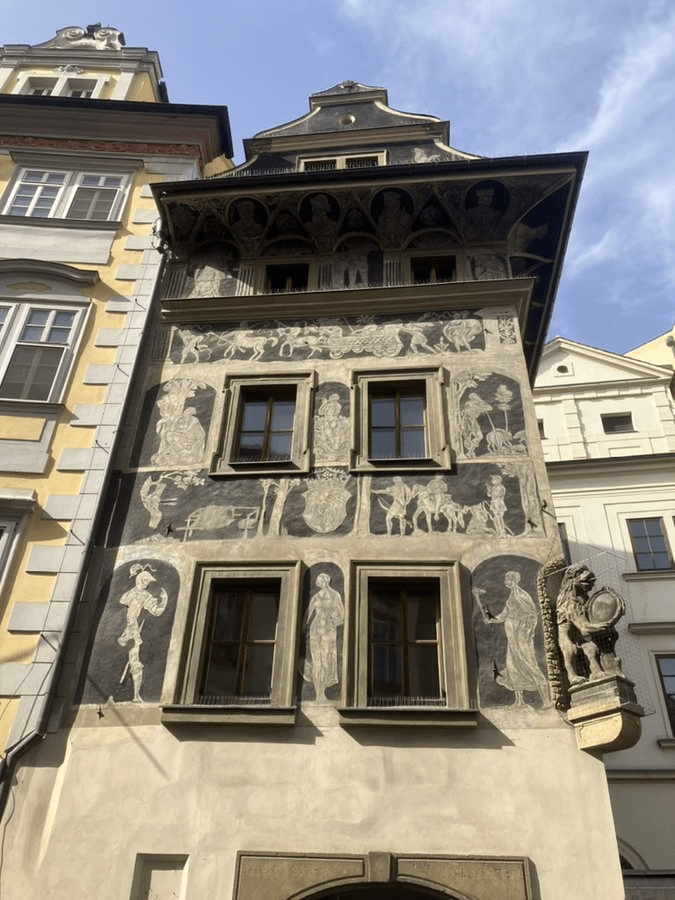

Dům U Minuty is famous not only for its freaking wonderful sgraffito decorations, but also because Franz Kafka lived here from 1889 to 1896 (and all three of his sisters were born here).

The Church of Saint Nicholas was built from 1732 to 1737, replacing what had been a centre of Hussite ideology back in the day. It was reinstated as a Hussite church in 1920.

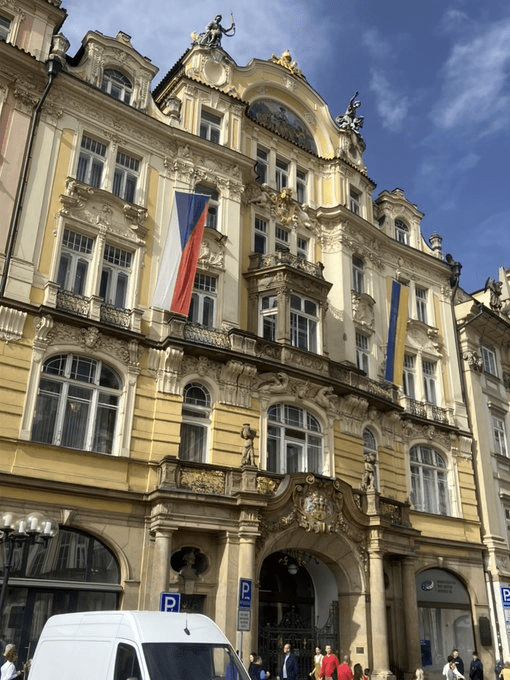

The former building of the Prague Municipal Insurance Company is now the Ministry for Regional Development of the Czech Republic.

(Briefly imagines getting to go to work on this square every day)

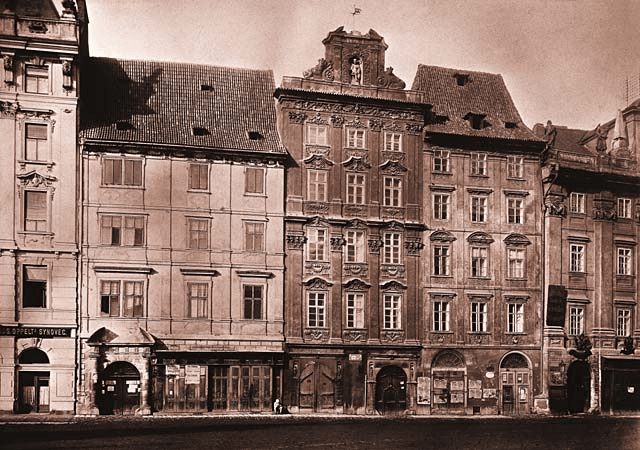

These are the buildings that were destroyed to make way for this one in 1899.

While here, what is now a restaurant was once part of a monastery dedicated to St Salvatore. The other buildings that were part of the monastery were destroyed as part of the ‘clean-up’ of Prague that took place in 1902-3.

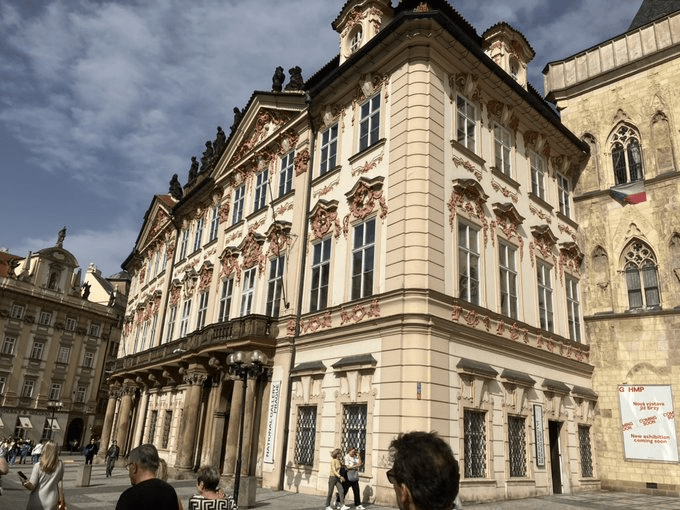

In 1843, Palác Kinských, a standout even on a square like this, was the birthplace of Bertha von Suttner. In 1905, she would become the first woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize.

Next door, U Kamenného zvonu (The Stone Bell) is used by the Gallery of the Capital City of Prague.

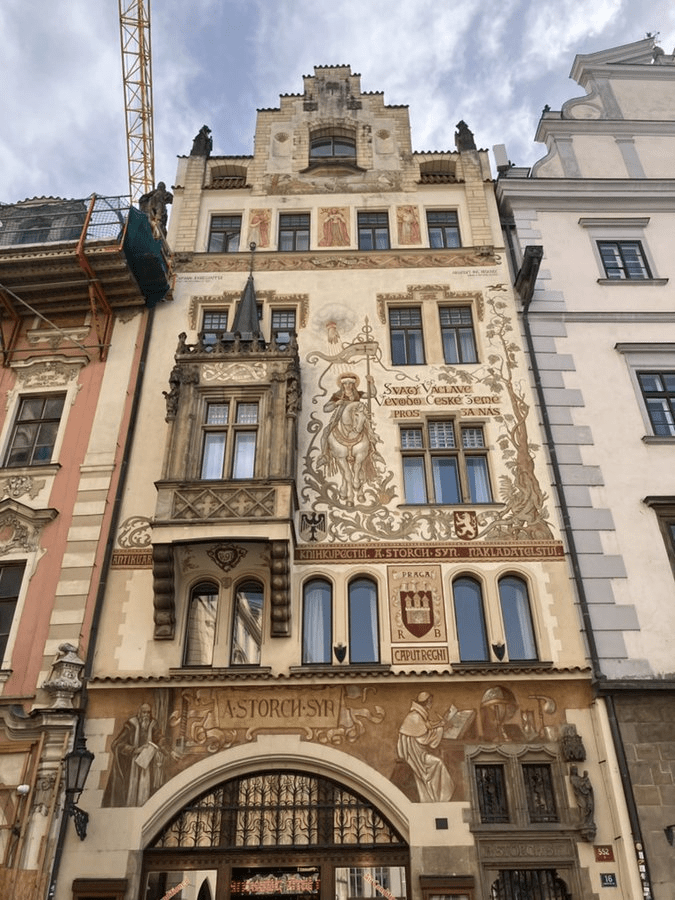

Štorchův dům was built in 1896-7 for a publisher, Alexander Štorch. What you see is a restoration from 1948 (with later modifications), as the house was burned down during the Prague Uprising in May 1945.

U Kamenného beránka (The Stone Lamb) was once a literary and cultural salon, run by Berta Fantová and attended by, among others, Albert Einstein, Christian von Ehrenfels, Max Brod and Franz Kafka (who we’ve established didn’t have much of a commute to get there).

U Červené lišky (The Red Fox) was purchased by Coast Capital Partners in 2017 for ‘the highest known sum in the Czech Republic that a buyer was willing to pay for a house in the centre’ (CZK 230,000 per square metre, and I don’t feel I’ve helped anyone by specifying that).

While I don’t have specific comments on Dům Na Kamenci other than that I love that colour.

In non-building territory, the Prague Meridian was used to tell the time until 1918 (high noon was determined by a shadow cast by the Marian Column). The marker on the ground says ‘The Meridian according to which time in Prague was determined in the past’ in Czech and Latin.

Seriously, though, what a city.

Leave a comment