Originally published on X on 7 April 2024.

Jiřík Černý was born around 1511 in Rožďalovice, near Nymburk, but there are no written mentions of him until 1534, when he gained a bachelor’s degree from the Faculty of Arts at Charles University.

At some point (the years after his graduation aren’t well documented either), he changed his name to Jiří Melantrich (which is Greek for ‘black-haired’).

His name does appear in 1545, when he published a book in Prostějov (Doktora Urbana Rhegia rozmlouvání s Annou, manželkou svou / ‘Dr. Urban Rhegius conversing with Anna, his wife’).

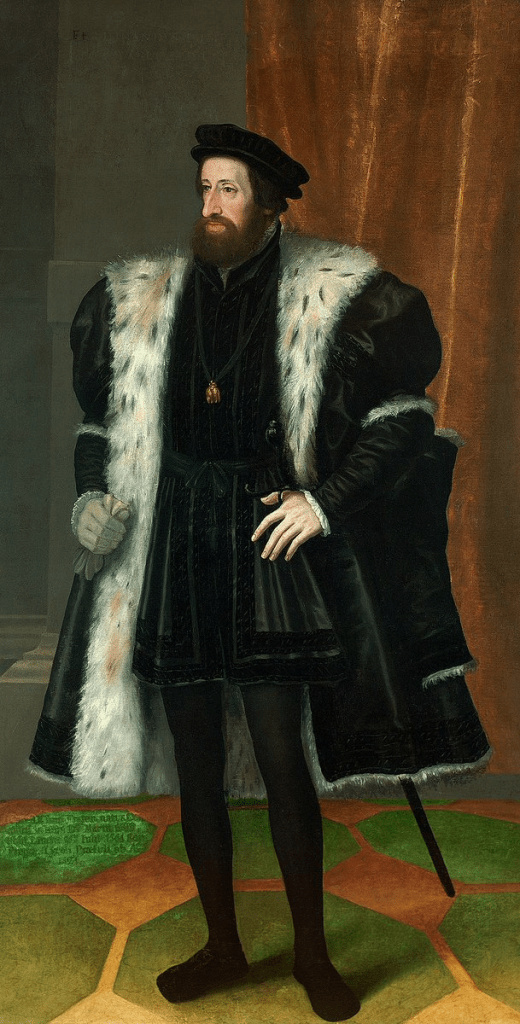

Melantrich moved back to Prague a year or two later, bringing some of his printing materials with him. In 1547, however, Ferdinand I (pictured) banned the printing of non-Catholic books due to the Estates Revolt in the same year.

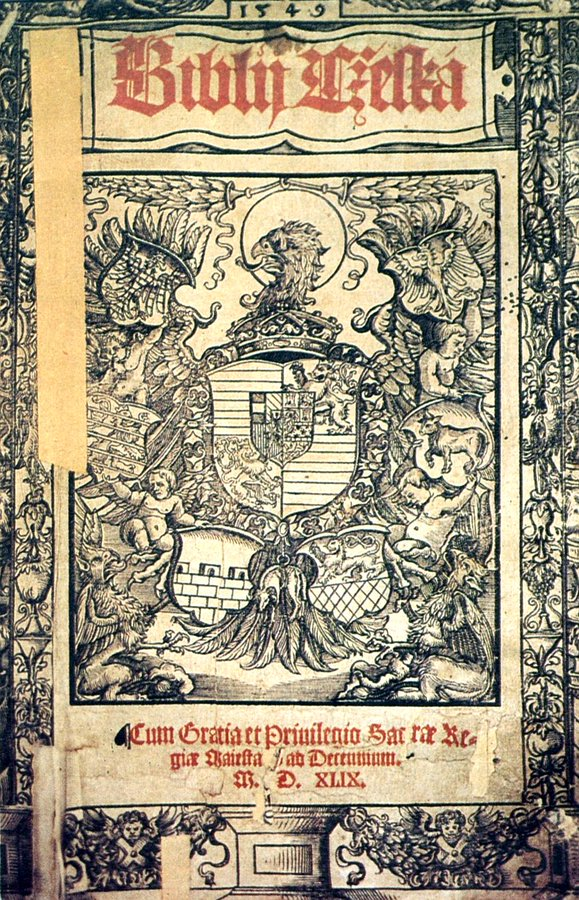

Melantrich got around this by joining a company owned by Bartoloměj Netolický, a Catholic. His most famous publication would be the Melantrich Bible, or the Melantriška for short, first published in 1549.

He would publish another 17 titles before buying Netolický’s share of the business in 1552 and essentially becoming a sole trader.

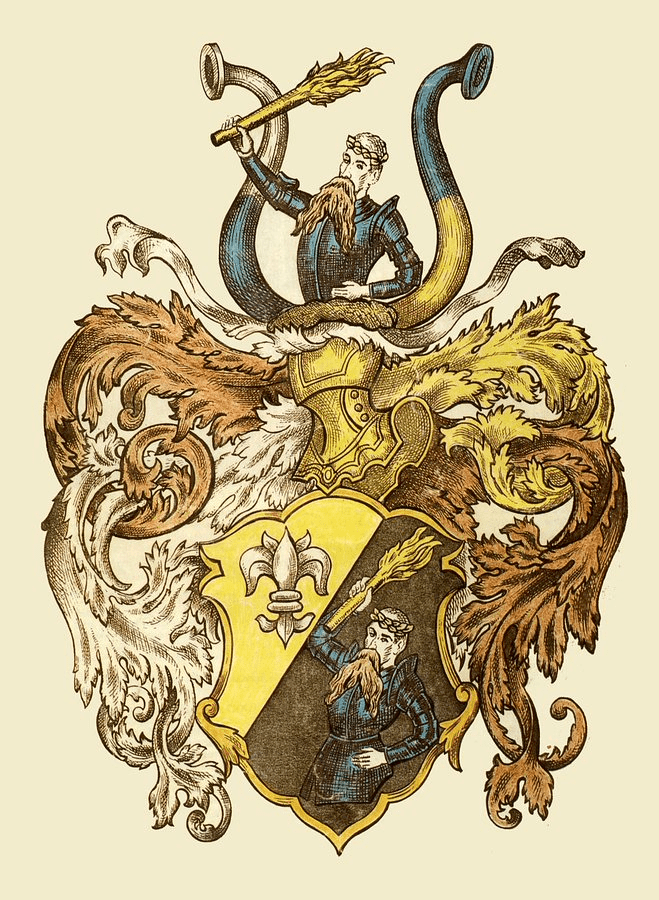

In 1557, Melantrich was awarded a coat of arms and became known as Jiří Melantrich of Aventino; in 1558, he became an alderman of Prague’s Old Town.

Key publications in the 1560s included Epistolarum Medicinalium libri quinque (Five Books of Medical Letters), containing medical letters written to patients by Pietro Andrea Mattioli, the Prague-based physician to King Ferdinand.

As well as Mattioliho herbář, a Czech translation of Mattioni’s Discorsi (full title probably too long to fit into three posts, let alone one), his analysis of 100 recently-discovered plants, and a key work in the field of botany.

He also published something with the excellent name of Knížka v českém a německém jazyku složená, kterak by Čech německy a Němec česky … učiti se měl – ‘A combined book in Czech and German, how a Czech should learn German and a German should learn Czech’ – in 1567.

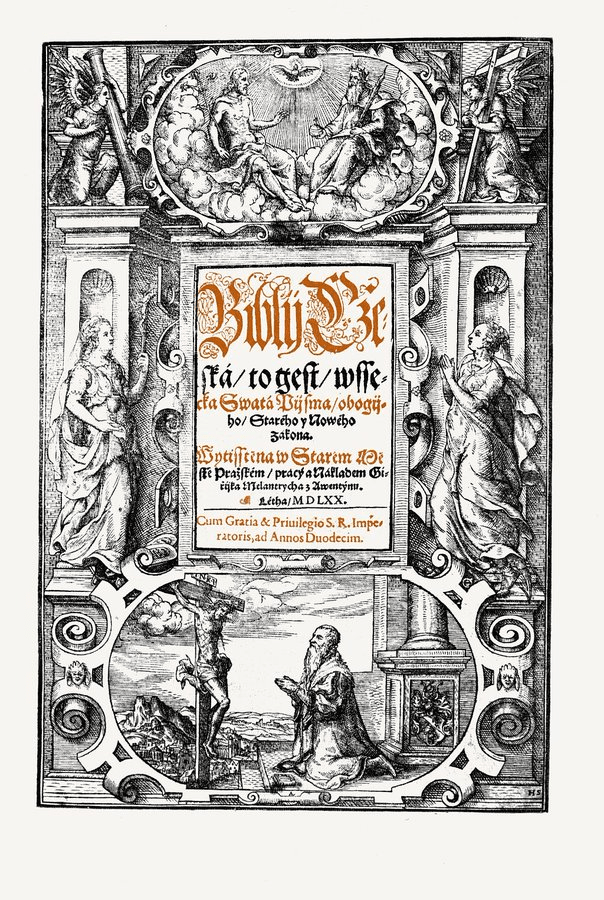

A new edition of the Bible, with new woodcuts, came out in 1570; interestingly (and unsurprisingly, given increased religions tensions at the time), it came under scrutiny from the Austrian censors despite its text being identical to the previous edition.

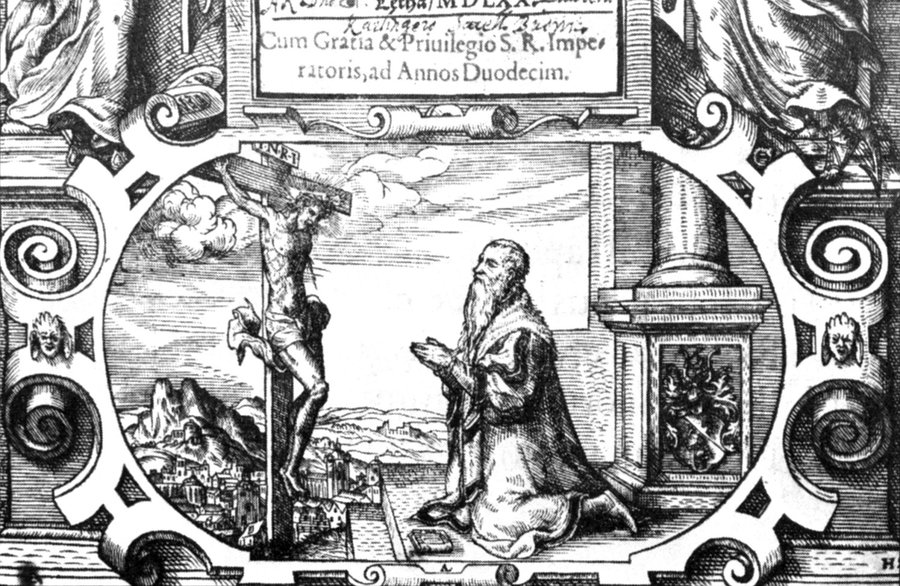

That picture includes the only depiction that we have of Melantrich from the time.

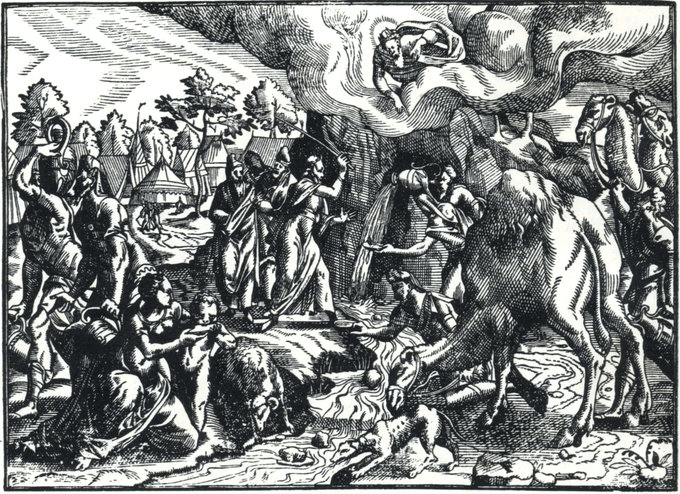

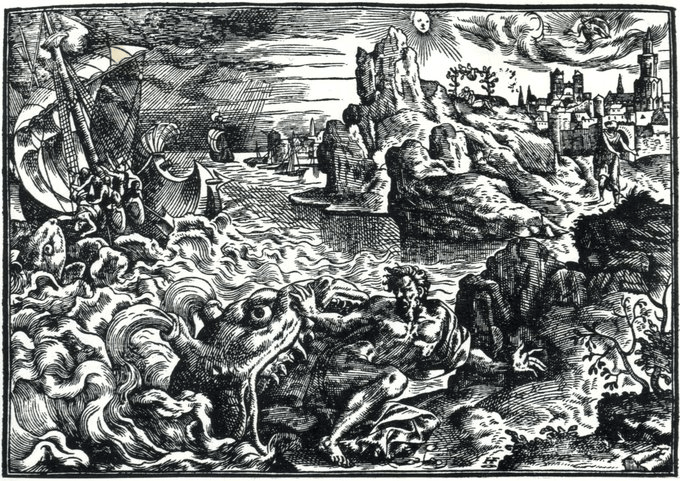

Inside, we have, for example, Moses drawing water from a rock in the desert and Jonah being thrown ashore by a whale.

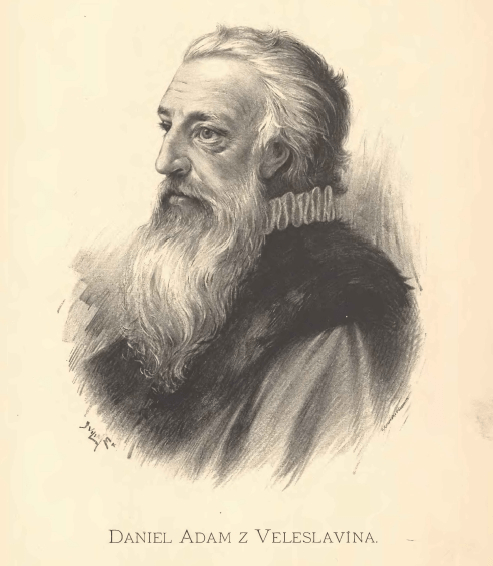

In 1576, Melantrich married his daughter Anna to Daniel Adam, a professor at Charles University, to whom he entrusted the printing house. However, their relationship became tense because Adam – known as Daniel Adam z Veleslavína from 1578 – answered back to the censors.

Melantrich died in 1580, having published at least 233 works in his lifetime, and was buried in the Bethlehem Chapel (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/10/01/prague-1-day-160-betlemske-namesti/). In a clear signal of how he felt about his son-in-law, he left the business to his son Jiří (and absolutely nothing to Veleslavín).

However, Jiří would die in 1586, so Veleslavín took over the business again. He, in turn, would die in 1599, after which Veleslavín’s son took charge. It was, expectedly, confiscated and given to the Jesuits after the Battle of Bílá Hora, and never regained its past glory.

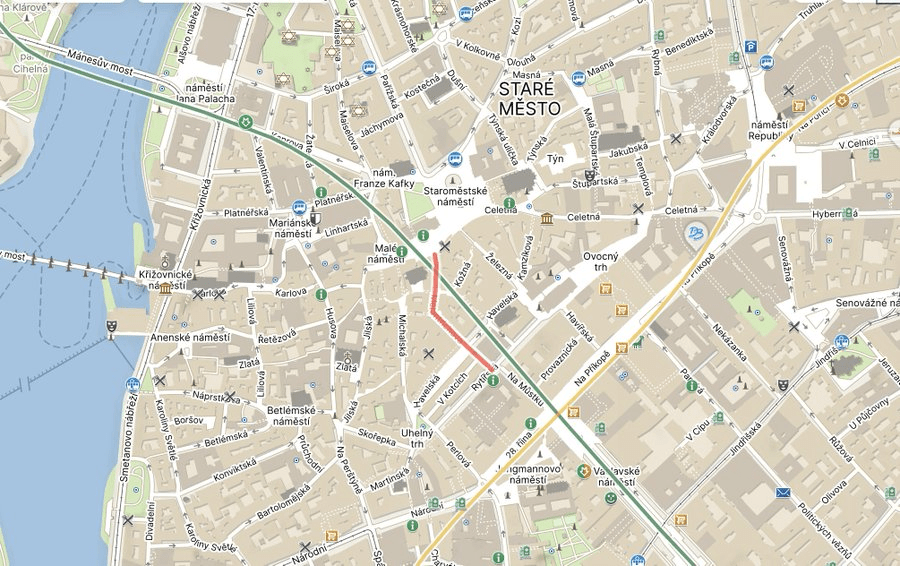

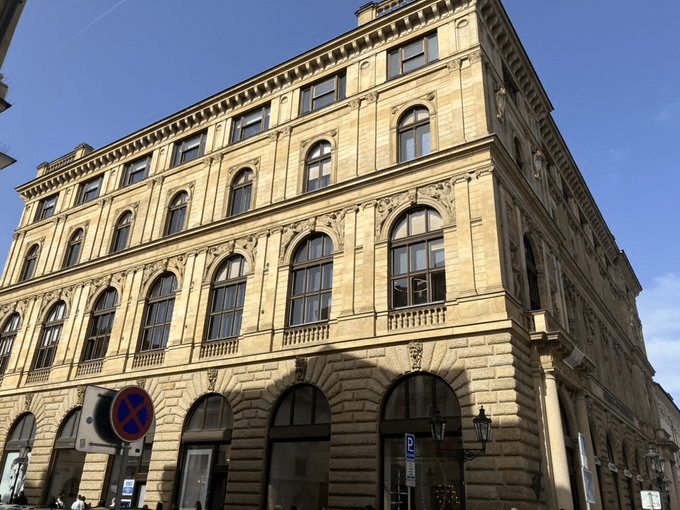

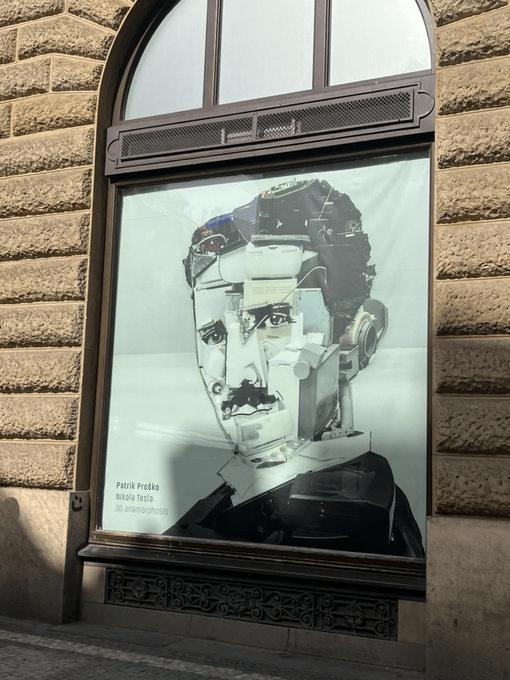

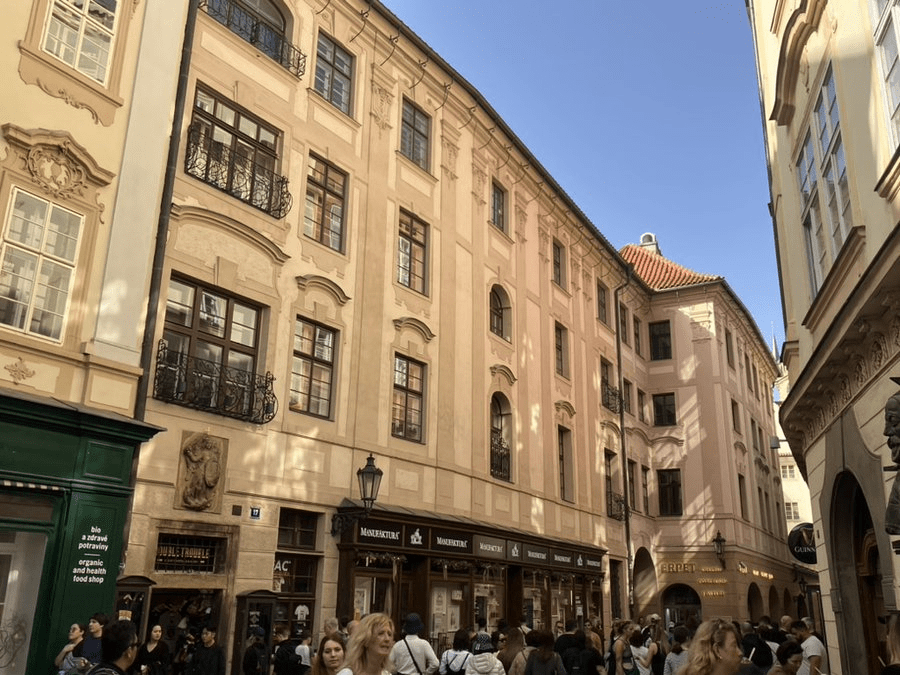

Melantrich’s family house on this street – which has had its current name since 1894 – is long gone, but you do get to enjoy, for example, the building created for the Municipal Savings Bank of Prague (1891, the work of Antonín Wiehl and Osvald Polívka). And its exhibitions.

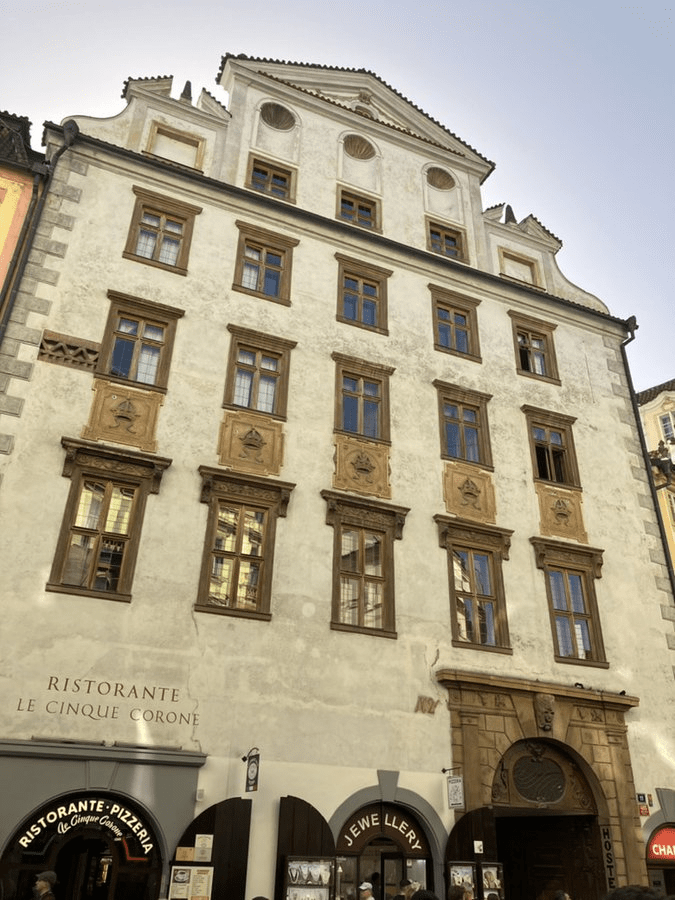

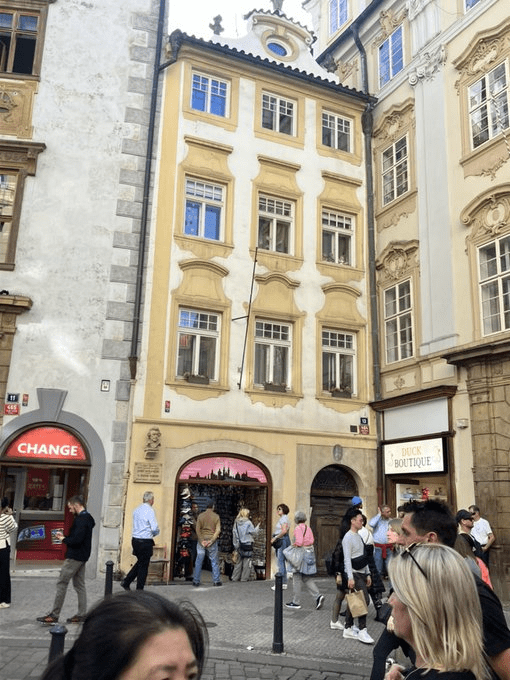

Or attractive Renaissance buildings such as U pěti korun (The Five Crowns; originally in Gothic style but redone in 1615).

Which is next to Dům U Košíku (The Basket) and Dům U Svatých Tří králů (The Holy Three Kings). Such beautiful buildings, yet people only ever walk past them in order to make it to the Astronomical Clock in time to see it do stuff for a few seconds.

While, a little further on, you’ve got three addresses which used to be the monastery of the Order of the Servants of Mary, i.e. the Servites, which was attached to St Michael’s Church (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/10/07/prague-1-day-173-michalska/).

Melantrich was also the name of a publishing company founded by the Czech National Socialist Party (not related to that one) in 1897. During the First Republic, it was Czechoslovakia’s biggest.

You may well recognise its former headquarters, especially if you’ve watched anything from November 1989 involving a balcony (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/17/prague-1-day-123-vaclavske-namesti/).

The printing house closed down in 1999.

Leave a comment