Originally published on X on 20 April 2024.

Franz Kafka was born in a house on the present-day square in 1883. It was called U Věže (At The Tower), and was destroyed as part the ‘clean-up’ operation in the Old Town in 1897.

His father, Hermann, was originally from Osek, a South Bohemian village with a large Jewish population. After working as a travelling salesman, he became a wholesaler of luxury goods in Prague.

His mother, Julie, hailed from Poděbrady, and was born into the family of a well-off retail merchant.

Kafka didn’t get on with his father, whom he described as despotic; both parents were away on business a lot and the children would largely be raised by servants and governesses.

Kafka had two younger brothers, Georg and Heinrich, who died in infancy, and three younger sisters, Gabriele (Elli), Valerie (Valli) and Ottilie (Ottla), who would all be murdered in the Holocaust.

The three sisters were all born in Dům U Minuty (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/10/12/prague-1-day-190-staromestske-namesti-old-town-square/).

From 1889 to 1893, Kafka attended the German Boys’ General School on Masná, then switching to the German State Gymnasium in Palác Kinských on Old Town Square, which (in things no child wants to experience) is also where his dad had his store.

The shop would move (a very short distance) to here in 1896: https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/10/09/prague-1-day-180-celetna/; this was the first time that Kafka would have a bedroom to himself.

In 1901, Kafka started to study chemistry at Karl-Ferdinand University. He switched to law after two weeks.

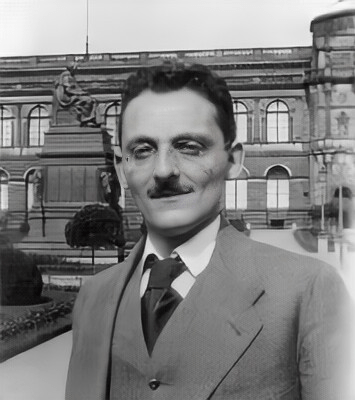

At university, he also befriended a fellow student, Max Brod (pictured in 1914).

Graduating in 1906, he soon took up employment at Assicurazioni Generali on Wenceslas Square (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/17/prague-1-day-123-vaclavske-namesti/).

Incidentally, 1906 was also the year in which the family business would move to another address on Celetná, Hrzánský Palace.

Resigning from the insurance company after less than a year, Kafka then got a job at the Workers’ Accident Insurance Company for the Kingdom of Bohemia on Na Poříčí, where he would work until 1922.

Kafka’s biggest gripe about both jobs was that they took up time that he could have spent writing instead; to make matters worse, his father still expected him to help out in the family shop.

On top of that, Kafka became a partner in Prague’s first asbestos factory, along with his brother-in-law, Karl Hermann, in 1911. Said factory was located in Žižkov: https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2023/01/14/prague-3-day-134-borivojova/.

Despite work commitments, the first publication of Kafka’s work (eight short stories, in this case) occurred in the Munich-based literary magazine Hyperion in 1908.

As a German-speaking Jewish inhabitant of Prague, Kafka was fascinated by Eastern European Jewry and Yiddish literature; however, he also felt alienated from Judaism and Jewish culture.

In 1912, Kafka met Felice Bauer, to whom he would be engaged twice (in 1914 and 1917, although they only met seventeen times during their five-year relationship). Kafka and Bauer first met at Max Brod’s house, which is U Mladých Goliášů on https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/27/prague-1-day-148-skorepka/.

It was also in 1912 that Kafka managed to write a short story, Das Urteil (The Judgement), in eight hours, starting a phase of intense creativity. It was published in Leipzig in the same year, and dedicated to Felice Bauer (this is the 1916 edition).

During his lifetime, only a few short stories of his, all of which were written in German, were published, and received little attention. The most famous is Die Verwandlung (The Metamorphosis), written in 1912 and published (also in Leipzig) in 1915.

As further proof of how productive 1912 was, Kafka also started on drafts for a work which he titled ‘Der Verschollene’ (The Man Who Disappeared); he continued with this until 1914, but left it incomplete; it would be published in 1927 as Amerika.

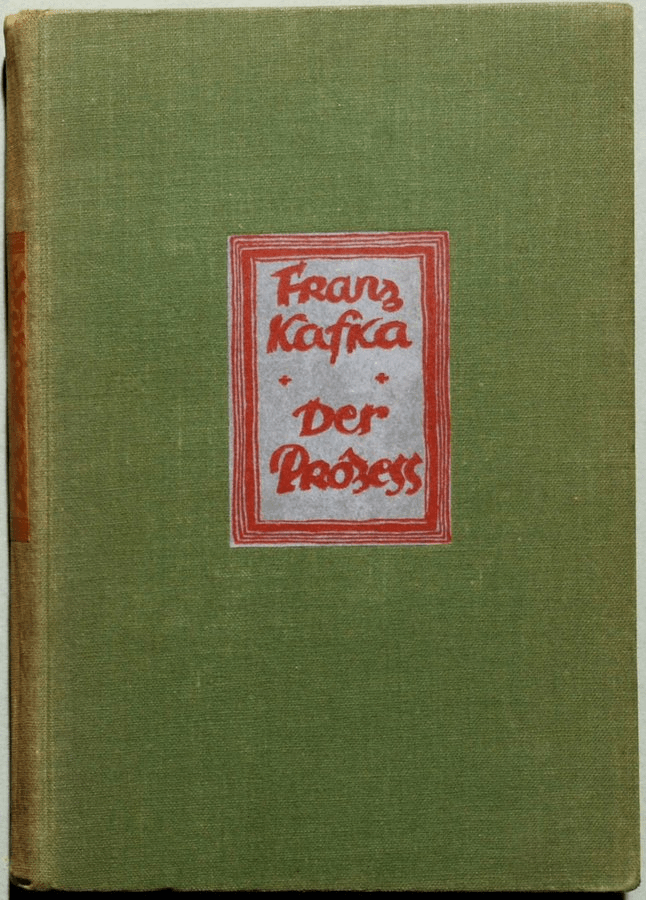

In 1914 qnd 1915, Kafka wrote Der Process (The Trial), which would appear in print in 1925 (yes, I would have assumed ‘Prozess’ too, but this is the spelling Kafka used).

He also planned a third novel, but didn’t start writing it just yet.

From 1916 to 1917, Kafka would stay in an apartment rented by his sister Ottilie on https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/05/prague-1-day-4-zlata-ulicka-u-daliborky/, where he could devote himself to his writing.

This was followed by renting an apartment at Schönborn Palace – now the US Embassy – on https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/08/prague-1-day-36-trziste/ from March to September 1917.

Here, that Kafka started to suffer from persistent bleeding, which his doctor identified as being caused by tuberculosis. He was granted long-term sick leave, going to Siřem, near Žatec, to recuperate (he’s on the right; his favourite sister, Ottla, is second from left).

Meanwhile, around 1919/20, he would become engaged to Julie Wohryzková, a hotel chambermaid. The engagement would only last a few months.

In 1920, Kafka had a largely correspondence-based relationship with a Czech (and non-Jewish) journalist, Milena Jesenská, who would translate some of his works into Czech and would publish an obituary for him in Národní listy following his death.

In 1922, Kafka finally found time to start on the other novel he’d been planning since 1914, Das Schloss (The Castle); like his other two novels, he never finished it, but it would appear in print in 1926.

As all attempts to improve his health failed, Kafka left his job for good in 1922. In 1923, he moved to Berlin in a bid to get away from his family and focus on writing, and lived with a kindergarten teacher, Dora Diamant.

However, his tuberculosis would return and spread to his larynx, leaving him unable to speak and only able to eat and drink with difficulty.

He died of heart failure on 3 June 1924, at a spa in Kierling, Lower Austria. He was forty.

He’s buried in the New Jewish Cemetery in Žižkov (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2022/11/28/prague-3-day-99-izraelska/).

In two letters to Max Brod – which were never sent – Kafka requested that all his unpublished works be destroyed, a wish that Brod chose not to respect, publishing the bulk of what he owned of Kafka’s writing between 1925 and 1935.

Kafka’s complete diaries from 1909 to 1923 would be published in German in 1994; a full English-language translation didn’t follow until 2023 (a version edited by Brod had appeared in the 1940s).

A distinctive statue dedicated to Kafka was unveiled in Prague in 2003 – we’ll get to that in a future post.

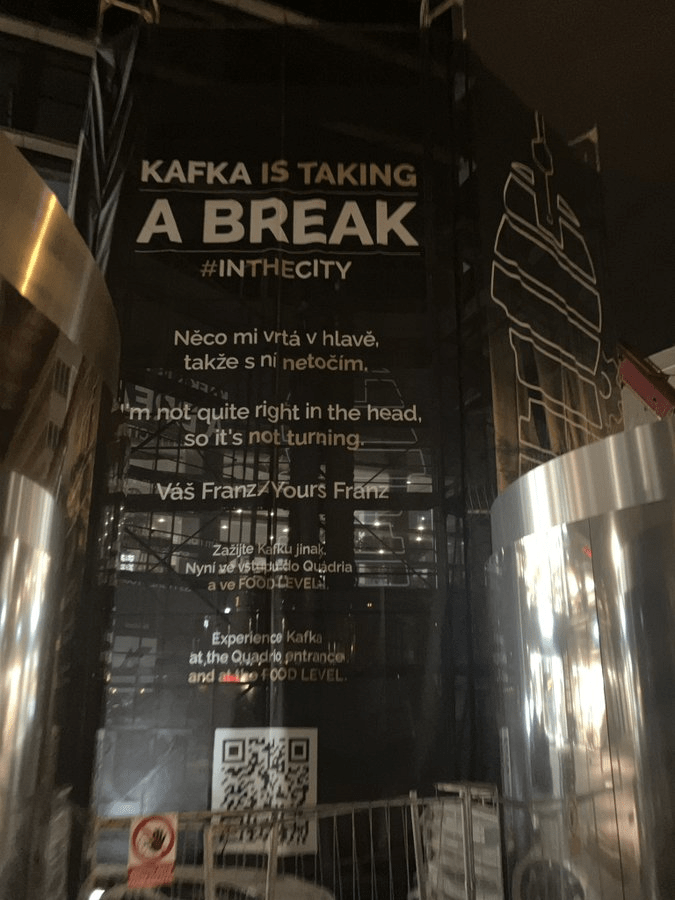

We’d also have a nice picture of David Černý’s mechanical tribute outside the Quadrio shopping centre near Národní třída if it hadn’t been closed for repairs when I took this photo last year:

And, of course, the museum: https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/08/prague-1-day-59-cihelna/.

Náměstí Franze Kafky was part of U Radnice (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/10/18/prague-1-day-203-u-radnice/) until 2000, when it became a separate street.

About Prague, Kafka wrote that ‘Prag lässt nicht los’ (‘Prague doesn’t let go’) and ‘Dieses Mütterchen hat Krallen’ (‘This little mother has claws’). A century after his death, it’s continuing to have that effect on me, and I hope those claws never stop clawing.

Leave a comment