Originally published on X on 27 April 2024.

Originally, this area was called Rejdiště (more on that in a few days); the square came into being in the 1870s and was called Na Rejdišti.

During WW1, it was named náměstí císařovny Zity after Zita of Bourbon-Parma (1892-1989), the final Empress of Austria and Queen of Hungary.

Then, from to 1919 to 1952, it was called Smetanovo náměstí (see https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/30/prague-1-day-156-smetanovo-nabrezi-smetana-embankment/), except during the Nazi occupation, when it was named after Mozart.

Then, in 1952, it was named náměstí Krasnoarmějců, after Red Army soldiers who were initially buried here in 1945. Streets named after Czechs who fell during that uprising? Not so much of a thing.

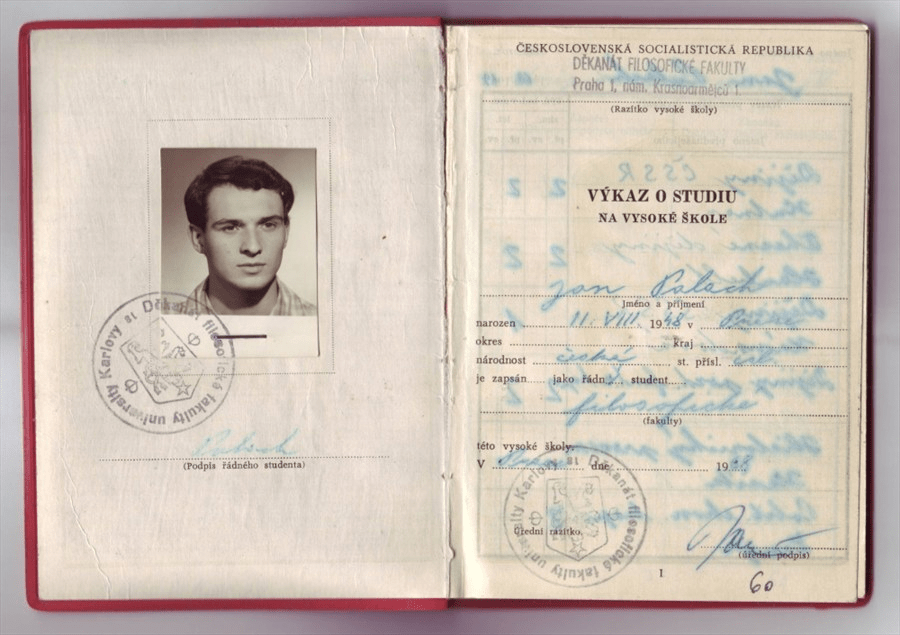

Jan Palach was born in 1948 in the sanatorium on Londýnská (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/03/03/prague-2-day-41-londynska/), but grew up in Všetaty, near Mělník.

His father, who died in 1962, had run a confectionery store until it was closed down by the Communists in the 1950s; this was used as a reason to stop Palach from entering the Faculty of Arts of Charles University in 1966, despite passing the entry exams.

Instead, he enrolled at the University of Economics (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2023/01/13/prague-3-day-126-namesti-winstona-churchilla/), and, in 1967, went on a student brigade in Kazakhstan, helping to fertilise the steppes.

In 1968, Palach’s second attempt to join the Faculty of Arts was successful, and, in the summer, he went on another brigade, this time to Leningrad. He came back to Czechoslovakia a few days before Warsaw Pact forces invaded the country.

In the aftermath, he participated in student strikes, but failed to see any progress being made, and had the overwhelming feeling that society was already becoming apathetic.

In early 1969, Palach sent a letter to several public figures, demanding that censorship be abolished, and that distribution of Zprávy (News), the occupying forces’ newspaper, cease.

On the afternoon of 16 January, Palach went to the top of Wenceslas Square (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/17/prague-1-day-123-vaclavske-namesti/), doused himself with flammable liquid, and set himself on fire.

He then ran to Washingtonova (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/18/prague-1-day-124-washingtonova/), where a worker tried to extinguish the fire.

Palach was taken to the burns clinic on Legerova (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2023/12/24/prague-2-day-8-legerova/ – see the bit about the mural).

From here, he gave a short interview, which was recorded. Please be warned that this is not an easy listen.

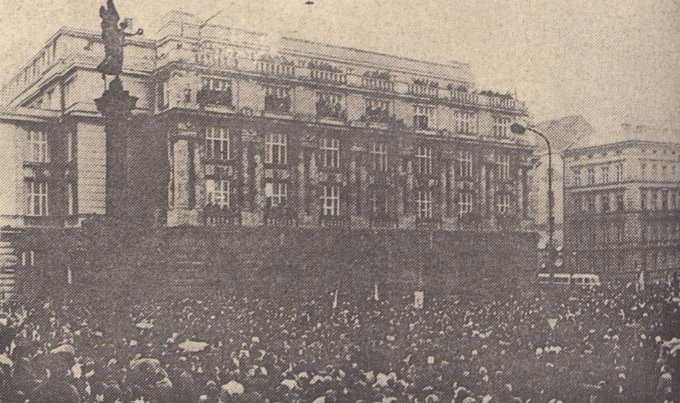

Palach died three days after his act, on 19 January. His death was followed by strikes at universities and secondary schools across the country, and his funeral on 25 January became a mass protest.

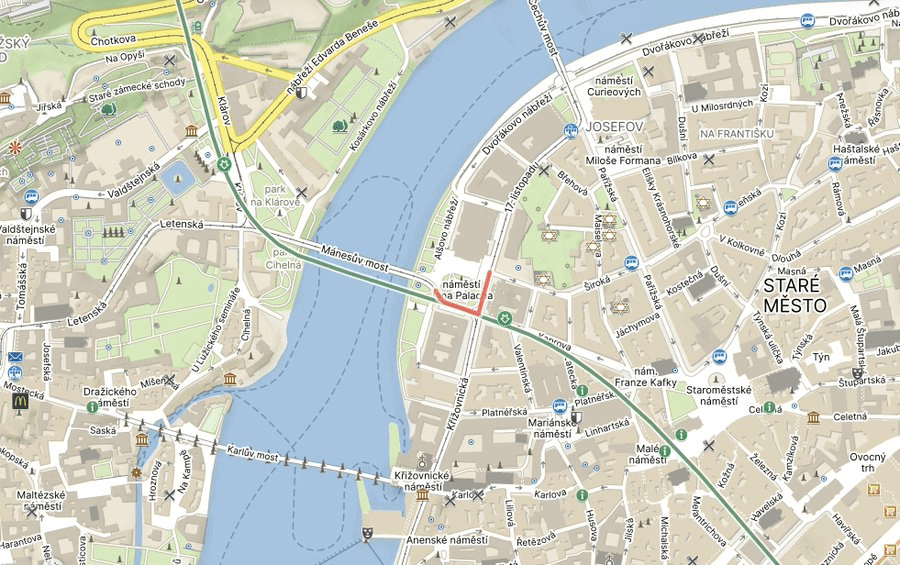

The funeral procession started at náměstí Krasnoarmějců – today’s square – and Palach was buried at Olšany Cemetery.

Within three months, another seven deaths by self-immolation had occurred in Czechoslovakia, the most remembered being that of 18-year-old student Jan Zajíc, who called himself ‘torch number two’ (see the Wenceslas Square post).

The Communist Party spread lies about Palach which his mother, Libuše Palachová, attempted to clear; she was supported in this by the dissident lawyer, Dagmar Burešová (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2023/12/23/prague-3-day-193-dagmar-buresove/).

Palach’s grave became something of a pilgrimage site, which worried the regime. Therefore, in 1973, Palach’s remains were cremated (his family was not informed in advance) and sent to Všetaty.

From 15 to 21 January 1989, a series of events, ostensibly to commemorate the 20th anniversary of Palach’s death, but also held to criticise the communist regime – were held.

These were brutally put down by the regime – a regime that, by the end of 1989, would no longer exist. The square was also renamed with remarkable speed – most street name renamings occurred in 1990, but this one took place in December 1989.

In 1990, Palach’s ashes were transferred back to Olšany Cemetery; the elementary school he went to (in Všetaty), as well as his secondary school (in Mělník) were both named after him.

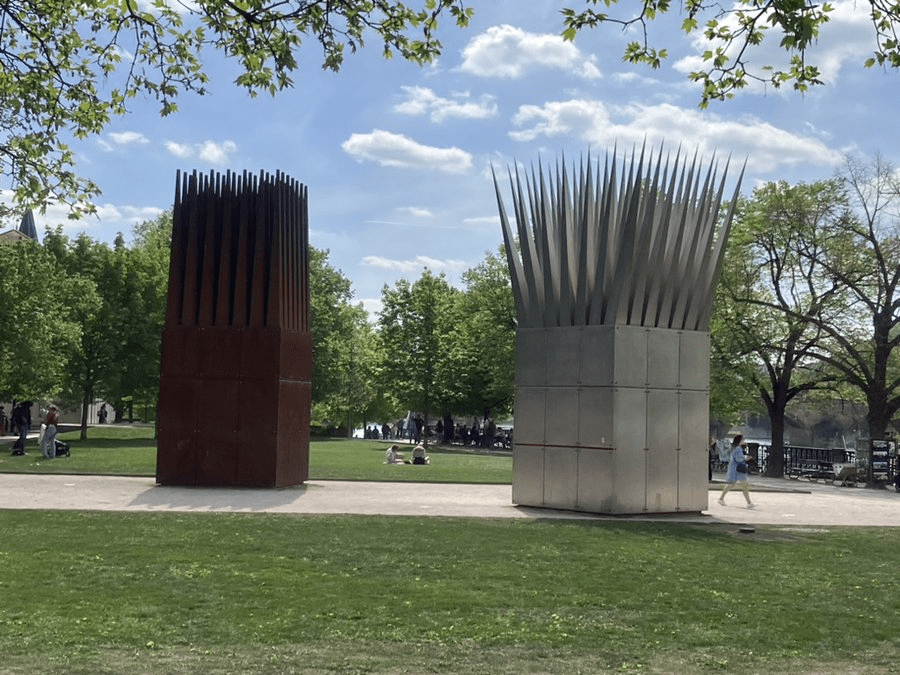

In 2016, a tribute to Palach, Dům sebevraha a Dům matky sebevraha (The House of the Suicide and The House of the Mother of the Suicide), by American artist John Hejduk, was placed on Alšovo nábřeží.

In 2004, British indie rock band Kasabian released Club Foot, the second single from their self-titled debut album. Its video is dedicated to Palach.

In 2013, Polish director Agnieszka Holland produced a three-part series for HBO about Palach’s deed and its aftermath, Burning Bush: https://english.radio.cz/hbo-drama-burning-bush-delivers-first-film-treatment-palach-story-8547986.

There was also a biographical film of Palach in 2019, directed by Robert Sedláček.

On the less high-brow side, Karel Gott’s cover of All By Myself (‘Where did my brother Jan go’), with lyrics by Zdeněk Borovec, was a tribute to Palach, although this was obviously not admitted to at the time.

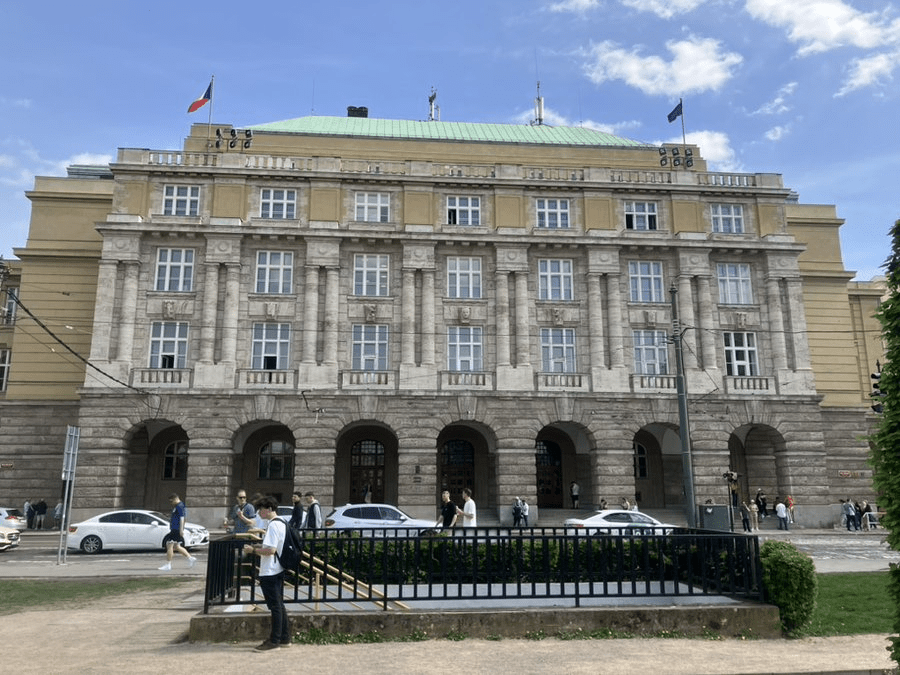

The Faculty of Arts of Charles University, founded by Charles IV in 1348, has been based on the square since 1929. As well as Palach, former students include Jan Hus (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/10/05/prague-1-day-169-husova/), Bernard Bolzano (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/19/prague-1-day-133-bolzanova/), Josef Jungmann (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/15/prague-1-day-111-jungmannova/), Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/01/prague-2-day-156-masarykovo-nabrezi/), Alice Masaryková, Karel Čapek (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/01/30/prague-2-day-24-sady-bratri-capku/) and Jaroslav Vrchlický.

Palach’s death mask, created by Olbram Zoubek, can be found on the wall of the building.

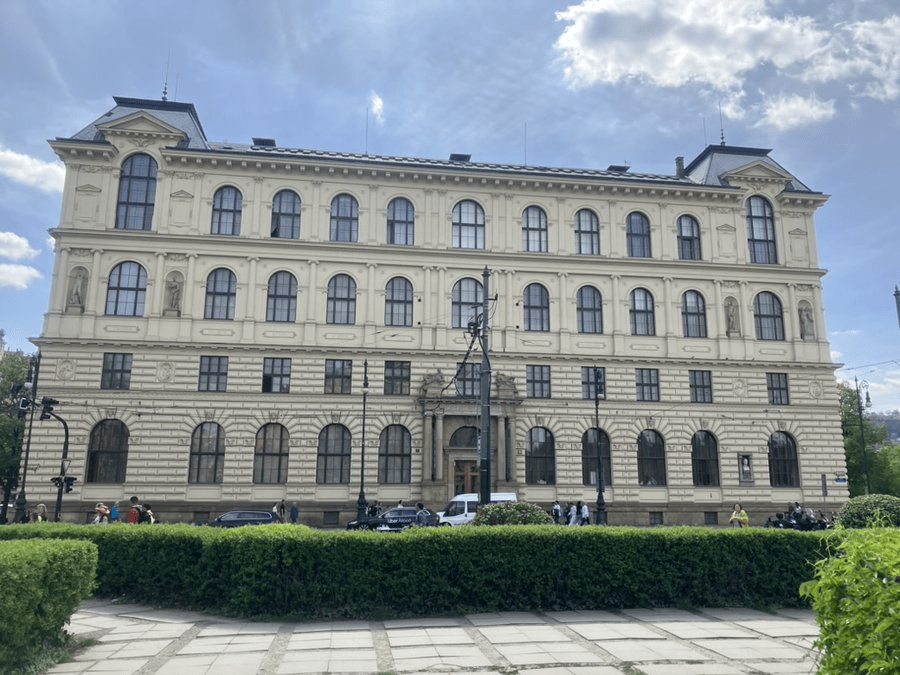

The University of Applied Arts in Prague (UMPRUM) also has its premises here. When it was opened in 1885, it was the first state arts school in Bohemia. Many of the country’s greatest talents have studied and taught here.

Appropriately, there’s a statue of Josef Mánes (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/01/18/prague-2-day-11-manesova/), one of the most important Czech artists, facing the University. I love how different these works look from different angles.

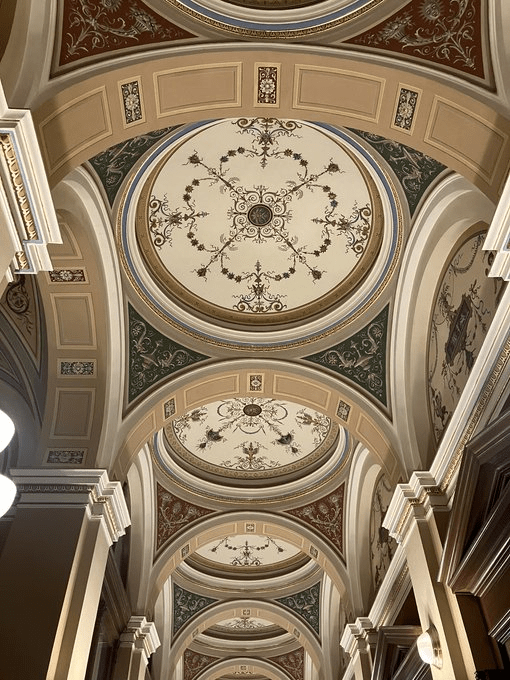

Opposite UMPRUM is the Rudolfinum, also built in 1885. It’s named after Rudolph, Crown Prince of Austria (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/08/prague-1-day-56-u-zelezne-lavky/), and, from 1919 to 1939, was the home of the Czechoslovak parliament.

Nowadays, it’s the home of the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra. I went to a concert here last year, and the insides are pretty special too.

A statue on the square commemorates Antonín Dvořák, who conducted the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra in its first ever concert, which took place in the Rudolfinum in 1896. He’s facing the concert hall.

Náměstí Jana Palacha is pretty lively at weekends.

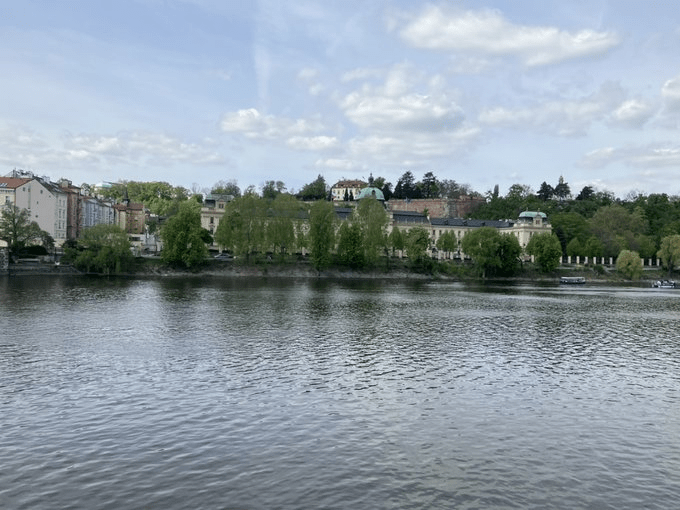

And, of course, the square offers excellent views across the Vltava, including a decent view of the toll house mentioned on https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/08/prague-1-day-54-kosarkovo-nabrezi/.

Finally, we all remember what happened on the square in December 2023. I am only mentioning it here to preempt anybody who asks why I’ve left it out, and to tell those people that it is still too horrific to think about, but that this is not the same thing as forgetting.

Leave a comment