Originally published on X on 9 May 2024.

Pierre Curie was born in Paris in 1859. He was educated at home by his parents (his father was a doctor), and took his baccalaureate in science when he was 16.

Two years later – when he was just 18 – he would already have a degree in physical sciences from the Paris Faculty of Sciences.

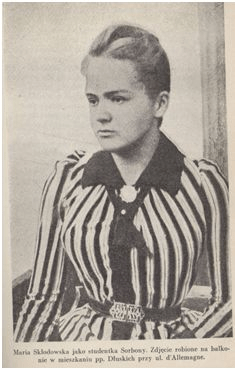

Meanwhile, Maria Skłodowska was born in Warsaw, then part of the Russian Empire, in 1867. Both her parents (pictured) came from families who had lost their property and fortunes due to their support for an independent Poland.

She studied at the Flying University, an underground institution (the ‘official’ universities didn’t allow women to enrol), along with her sister Bronisława (right), who went to study medicine in Paris.

In 1891, Maria would join her; in France, she came to be known as Marie. She obtained a degree in physics from the University of Paris in 1893, followed by a master’s in mathematics in 1894.

A mutual friend, the Polish physicist and diplomat Józef Wierusz-Kowalski, introduced Pierre and Marie to each other. They would marry in 1895, the same year in which Pierre received his doctorate.

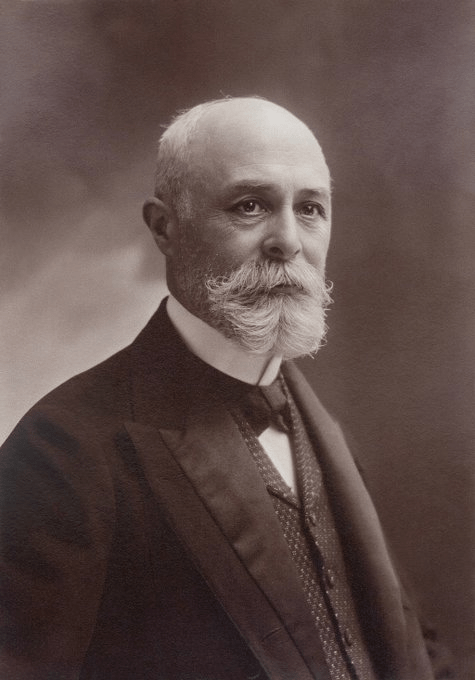

Also in 1895, Wilhelm Röntgen discovered X-rays, and, in early 1896, Henri Becquerel started experiments which would lead him to conclude that uranium salts emitted rays of their own accord.

Using an electrometer which Pierre had developed with his brother in the early 1880s, Marie discovered the uranium rays could make the surrounding air conduct electricity, and hypothesised that radiation came from the atoms themselves.

In 1898, she discovered that thorium was also radioactive. Pierre dropped his research to join his wife on hers.

In the same year, they would announce the discovery of two more elements: polonium, named after her native (and partitioned) Poland, and radium; they also coined the term ‘radioactivity’.

They published 32 scientific papers in the next four years, one of which stated that exposure to radium caused tumour-forming cells to be destroyed more quickly than others.

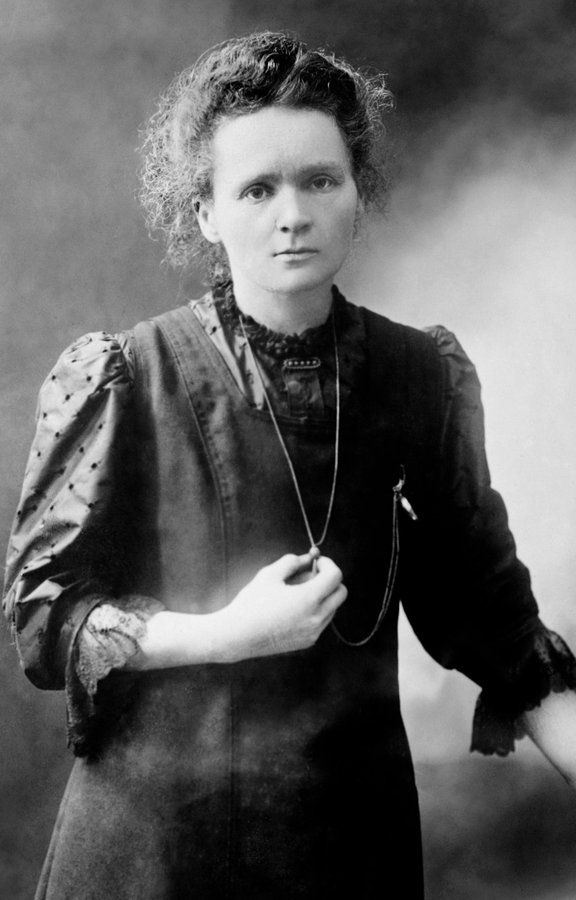

In June 1903, Marie received her doctorate, and the couple went to the Royal Institution of Great Britain in London to give a speech, although Pierre was only allowed to speak, because sexism and some people generally being awful.

In December 1903, Pierre, Marie and Henri Becquerel received the Nobel Prize for Physics. Marie was the first woman to win a Nobel prize, although – more sexism alert – a committee member had to lobby hard for her to be nominated at all.

In 1906, Pierre was struck by a horse-drawn vehicle on the Rue Dauphine in Paris and died instantly. He was 46.

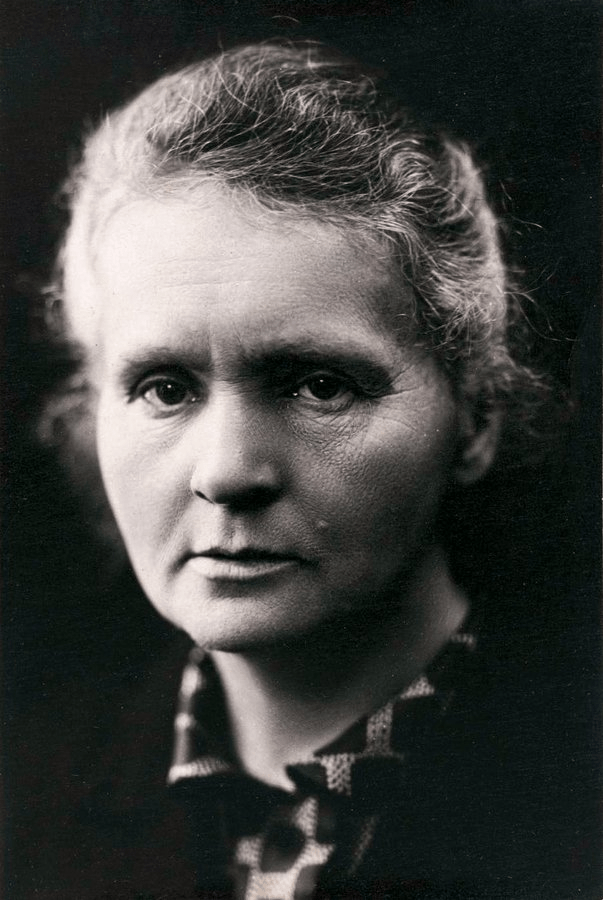

A devastated Marie was given the chair of the physics department at the University of Paris, becoming the university’s first female professor.

In 1909, she founded the Institut du Radium, now known as the Curie Institute; in the following year, she managed to isolate radium. The term ‘curie’ was first attributed to a unit of radioactivity in 1910, too.

However, large chunks of the French public continued to see her as ‘not one of theirs’, especially when she was revealed to have had an affair with Paul Langevin, a former student of Pierre’s who was separated, but not divorced from, his wife.

In 1911, Curie would win a second Nobel Prize, this time in chemistry. The chair of the Nobel Committee encouraged her not to turn up to collect her prize, given her private life; she ignored him.

During World War I, Curie created mobile radiography units (‘petites Curies’), used to treat an estimated one million French soldiers.

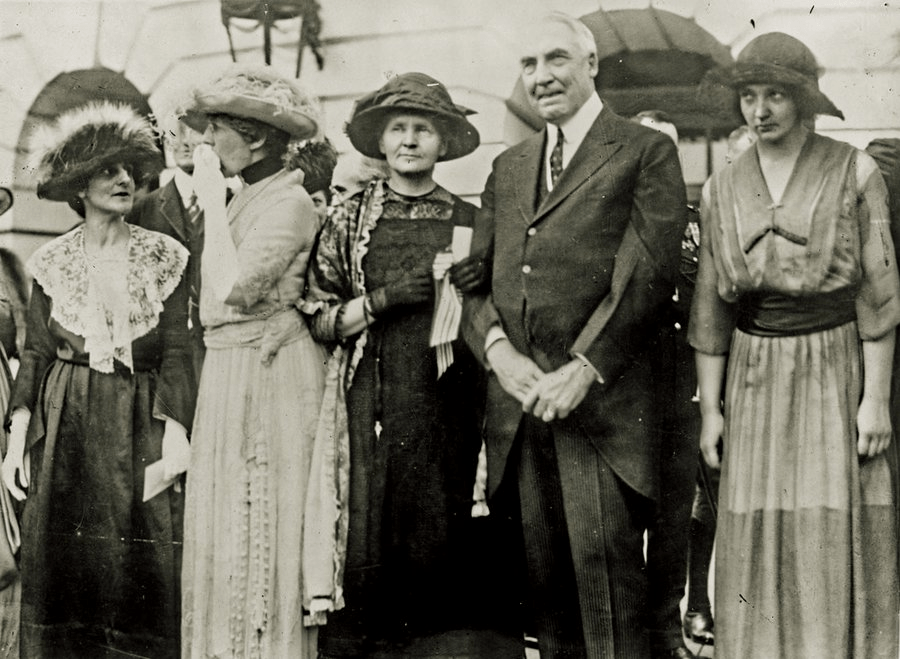

In 1921, Curie visited the White House and also turned down the Legion of Honour (possibly thinking France’s gratitude was a case of too little, too late); in 1922, she joined the League of Nations’ International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation.

Curie died in 1934 from aplastic anaemia (when the body fails to produce enough blood cells); a study in 1995 concluded that this was more likely due to her use of radiography in WW1, rather than exposure to lethal levels of radiation during her experiments.

In 1935, her daughter and son-in-law, Irène and Frédéric Joliot-Curie, would receive the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their discovery of induced radioactivity.

Both Marie and Pierre were buried in Sceaux, in the southern suburbs of Paris; their remains were transferred to the Panthéon in 1995.

Her name has been given to an EU fellowship programme, a metro station in Paris, numerous academic institutions, and a British charity providing hospice care.

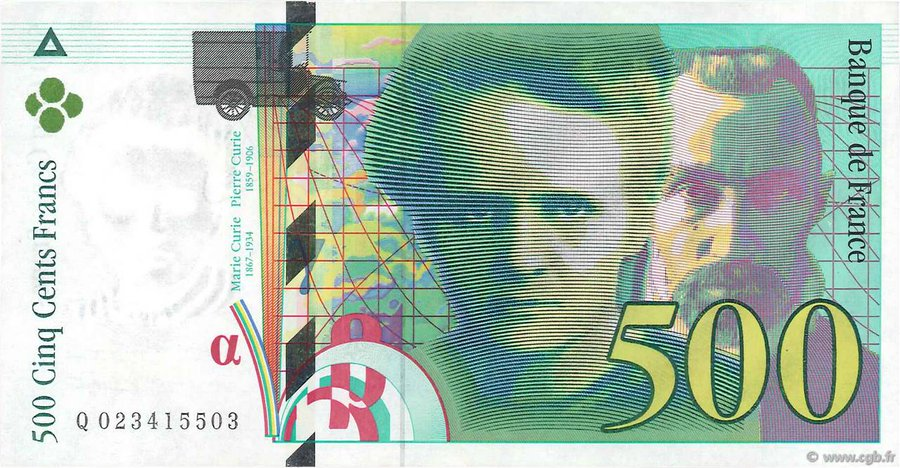

She’s also on French fifty cent coins, having previously been on French 500 franc notes when those were a thing.

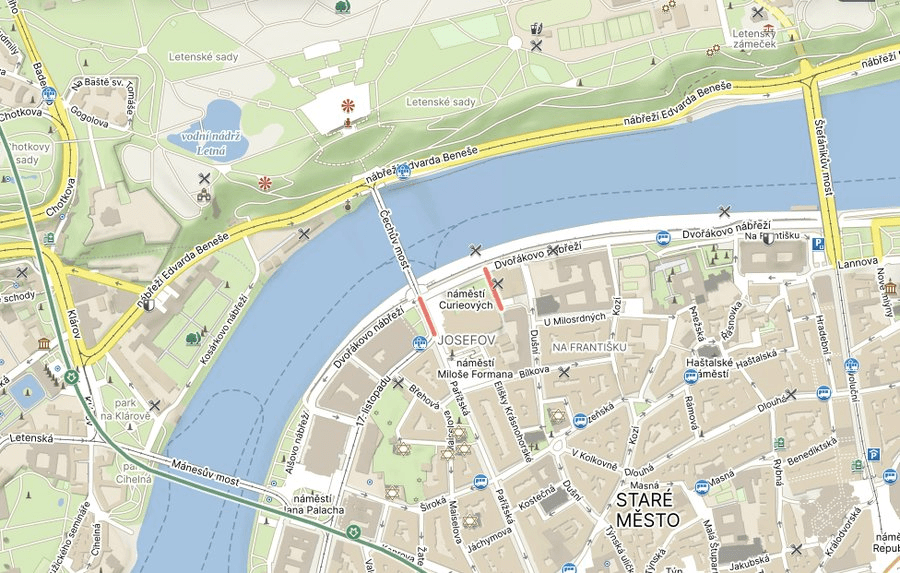

Náměstí Curieových was given its current name in 1960. Before that, it was called Janské náměstí, apparently because John of Nepomuk’s body was fished out of the Vltava here in 1393.

The square includes the entrance to the Law Faculty of Charles University; the faculty was founded in 1348, but the building was created between 1924 and 1931.

It was here that students were arrested by the Nazi police after the funeral of Jan Opletal (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/18/prague-1-day-125-opletalova/) in 1939.

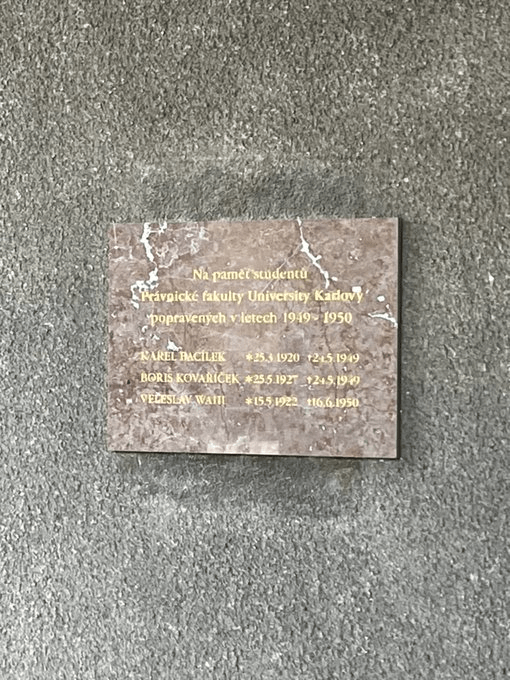

There are also plaques commemorating those who died here during the Prague Uprising in May 1945, and those students executed by the Communists in 1949 / 1950.

Across the road is what was opened in 1974 as Inter-Continental Praha, and is apparently due to reopen as Fairmont Golden Prague sometime in 2024 (in other words, what you currently see is a building site).

Leave a comment