Originally published on X on 12 June 2024.

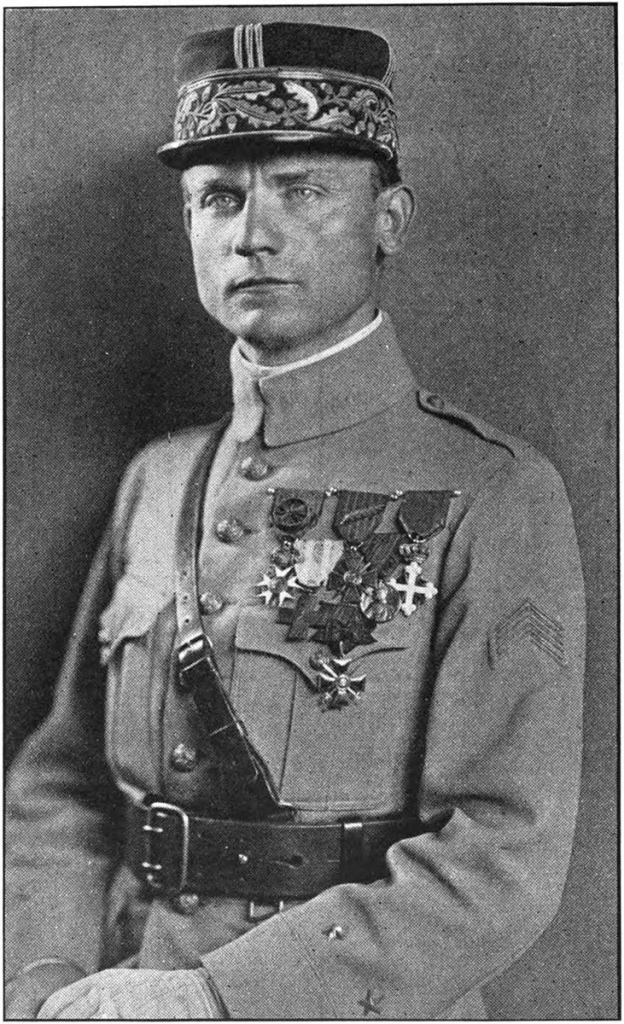

Milan Rastislav Štefánik was born in Košariská, a village nowadays in the Trenčín Region of Slovakia, in 1880.

He was the son of an evangelical priest, Pavol Štefánik, who raised his children to be interested in Slovak history and culture.

Leaving his village at nine, he went to school at the Evangelical Lyceum in Bratislava, but had to move because his brother – also studying there – didn’t get good enough grades to continue. He then studied in Sopron and Szarvas (both now in Hungary).

An outstanding student at all three schools, Štefánik then went to Prague to study civil engineering. During his studies, Štefánik started to take an interest in the progressive ideas of a professor, one T. G. Masaryk (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/01/prague-2-day-156-masarykovo-nabrezi/).

In 1900, he started to study astronomy and physics at Charles University; in 1901, he became chairman of Detvan, the Slovak student association.

In 1903, Vavro Šrobár, a Slovak doctor and politician (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2023/03/02/prague-3-day-167-srobarova/), who had founded Detvan, relaunched his magazine, Hlas (voice). Štefánik helped edit its artistic section.

He also wrote articles which aimed to inform Czechs of the difficult situation that Magyarisation was creating for Slovaks.

He somehow found time to graduate during all this (in 1904), and then moved to Paris.

After a difficult start, Štefánik got a job at the Paris Observatory, a job which enabled him to observe the Moon and Mars from Mont Blanc, and to witness a full eclipse in Alcossebre, near Valencia.

Later losing his job (the new owner of the Observatory seriously disliked him), a new opportunity came when the French authorities allowed him to go on trips to, amongst other places, Tahiti (where he observed Halley’s Comet).

He wanted to settle there, but the French authorities had other ideas – they wanted him to travel to Ecuador and the Galapagos. Štefánik’s career was also thwarted by health problems.

These problems – and a stomach operation – meant that his desire to join the Western Front in WW1 was delayed until 1915, when he qualified as a pilot from the military aviation school in Chartres.

Seeing the opportunities for emancipation from Austria-Hungary that WW1 could bring, Štefánik tried to create a unit of Czech-Slovak volunteers.

In September 1915, he was transferred to Serbia, but his time there was cut short by a plane crash and illness; after receiving treatment in Rome, he headed back to Paris.

Having been introduced to Prime Minister Aristide Briand – and, in December, to Edvard Beneš – Štefánik pushed for the creation of a central representative body of Czechoslovak foreign resistance.

In February 1916, this led to the founding of what would become the Czechoslovak National Council, where he and Beneš were vice-chairmen (the chair was Masaryk).

After another bout of ill health, Štefánik went to Italy, then to Russia, then to Romania, to spread the word. The trip to Romania resulted in 1,500 volunteers being found.

Further success came in early 1917, when the temporary government in Russia gave its support, and also when Štefánik travelled to the USA and gathered another 3,000 volunteers.

In December 1917, the French government signed the Decree on the Creation of the Czecho-Slovak Army in France. Negotiations with the Italian government were more of a challenge, but also resulted in an agreement being signed in April 1918.

On 28 October 1918, when Czechoslovakia became independent, Štefánik was its first Minister of War (Šrobár was Minister of Health).

Much of his work in this period was spent working out what to do with the Czechoslovak legions who were stuck in Siberia, after Russia had become communist and decided that it cared as much about Slavic solidarity as it does in 2024: https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/12/prague-1-day-90-most-legii-legion-bridge/.

By this point, Štefánik hadn’t been to his motherland since his father’s death in 1913. On 4 May 1919, he boarded an aircraft near Udine in Italy, intending to fly to Slovakia.

While a definitive account of events is not available, the plane crashed at Ivanka pri Dunaji, near Bratislava. All those on board were killed, including Štefánik, who was 38.

In Bratislava, an embankment, a bridge and the airport were all named after him. He’s also been seen on various coins, stamps and banknotes (this one is from 1926).

And these quite fetching 20 koruna coins, issued in 2018, 100 years after Czechoslovak independence.

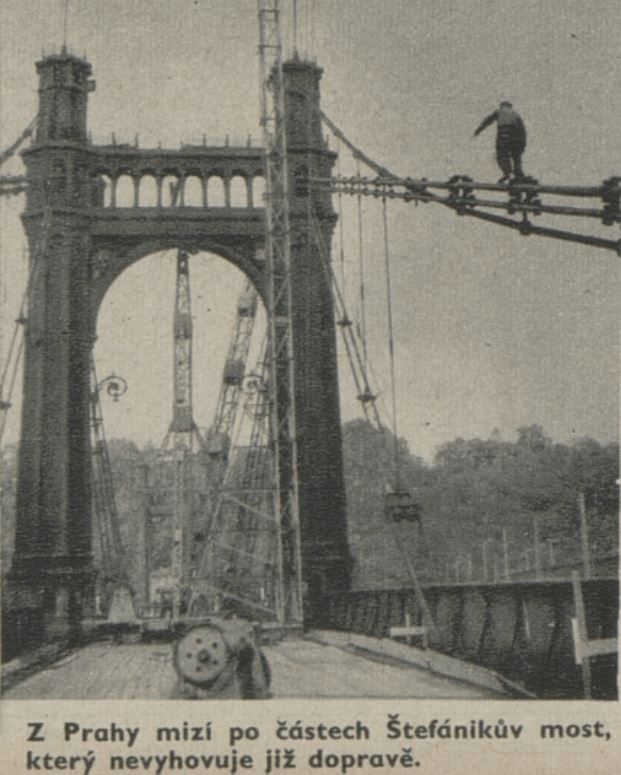

We need to talk about the history of the bridge too. Originally, this was the site of the Emperor Franz Joseph I Bridge, built between 1865 and 1868. It was promptly renamed Štefánikův most upon Štefánik’s death in 1919.

The bridge was dismantled in 1946/7, and replaced by the current bridge between 1949 and 1951.

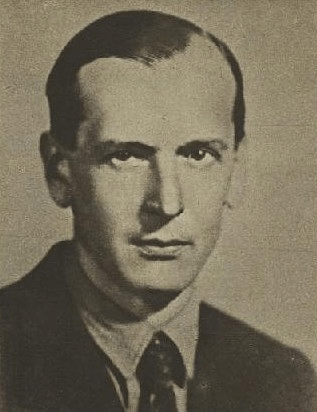

From 1947 until 1997, it was named Švermův most, after Jan Šverma (1901-44), a journalist, communist activist and resistance fighter against the clerical fascist Slovak State.

A statue which stood on the bridge is now at Olšany Cemetery (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Jan_%C5%A0verma#/media/File:Jan_Sverma_memorial_Olsany_Cemetery_Prague_CZ_052.jpg/2); meanwhile, Jinonice Metro Station, on the yellow line, was also known as Švermova when it opened in 1988.

Leave a comment