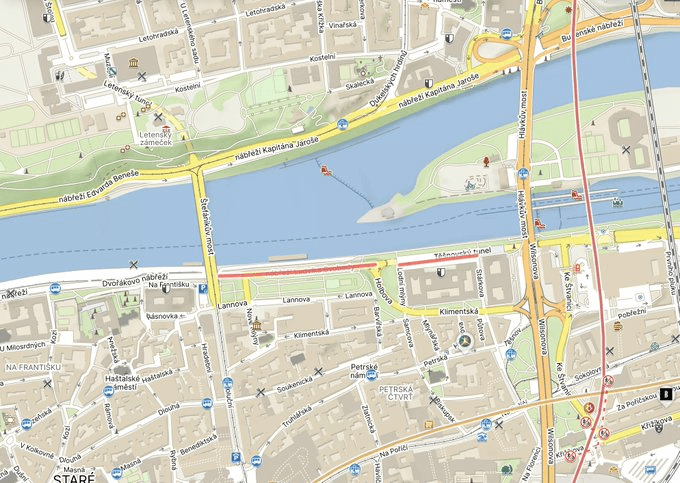

Originally published on X on 15 June 2024. ‘Nábřeží’ = ‘Embankment’.

Ludvík Svoboda was born in Hroznatín, a village in Vysocina Region, in 1895. His father died a year later (apparently after being kicked by a horse), and his mother remarried in 1898.

He attended the Agricultural School in Velké Meziříčí, and was then called up to the Austro-Hungarian Army in 1915. He was captured in Ternopil, and trained as part of the fire brigade of the city of Kyiv.

In 1916, he enrolled in the Czechoslovak Legion, and, in 1917, took part in the Battle of Zborov (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2022/12/04/prague-3-day-111-pod-vitkovem/).

He then took part in the battles for the Trans-Siberian Railway (see https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/12/prague-1-day-90-most-legii-legion-bridge/), and, when Russia became communist, was one of the soldiers stuck a long way from home.

His journey home – once Czechoslovakia had become independent – therefore had to go via Japan, the Pacific, the Panama Canal, and the United States.

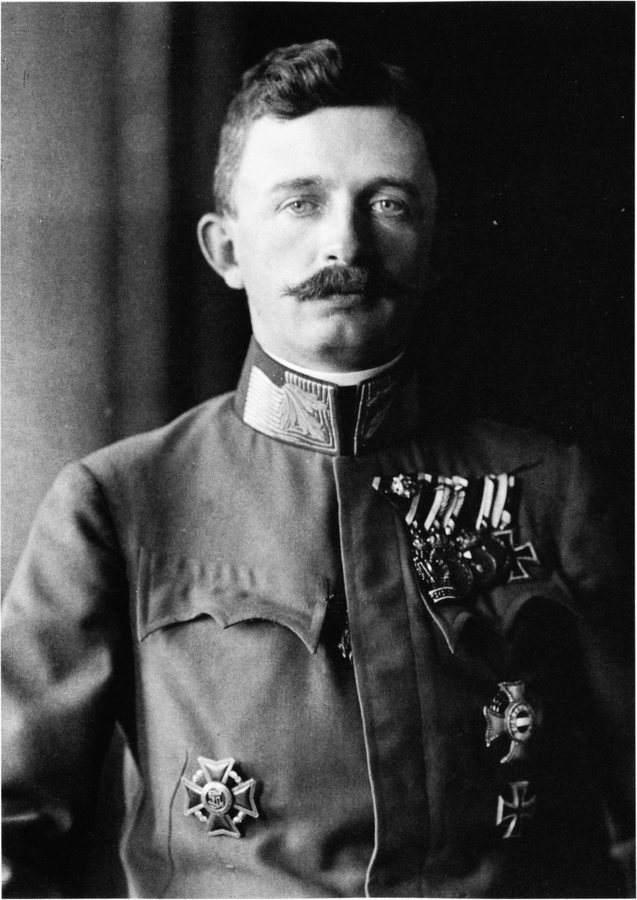

Initially taking over the family farm, Svoboda was soon remobilised in reaction to events in Hungary (in 1921, Charles I, the last Emperor of Austria-Hungary (pictured), made two attempts to retake the Hungarian throne).

Svoboda married Irena Stratilová (pictured in her future First Lady days) in 1923, and, in the same year, joined the 36th regiment in Uzhhorod (then still in Czechoslovakia) as a staff captain. He would stay there for eight years.

Afterwards, he was moved to Hranice, where he taught Hungarian at the Military Academy for three years, and, in 1934, was promoted to lieutenant colonel, and moved to the Jan Žižka 3rd Regiment in Kroměříž, which he had already served in from 1921-3.

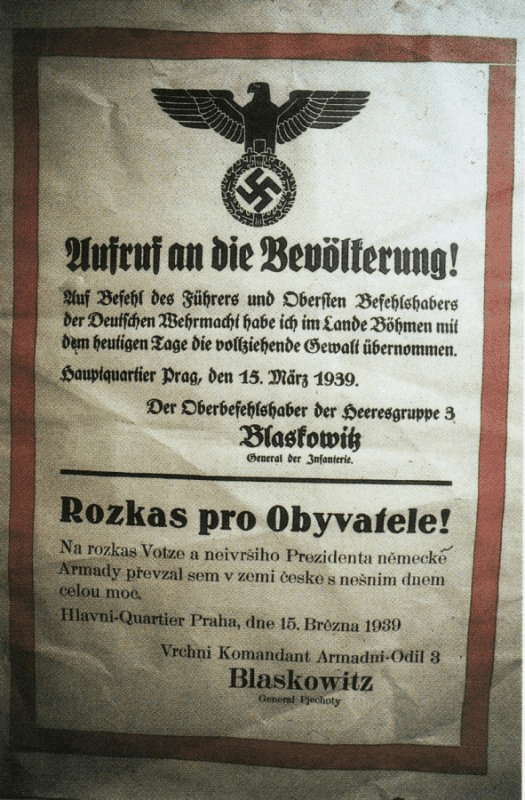

Being promoted to commander of the reserve battalion, this obviously became a bigger deal as war once again loomed. After the Nazis occupied Bohemia and Moravia in March 1939, Svoboda started to work for the Czech resistance.

He managed to get to Poland, where he formed a Czechoslovak unit in Kraków, transferring 700 men to the Soviet Union when Nazi Germany invaded Poland in September. In the USSR, they were confined to Czechoslovak-adminstered camps.

In July 1941 – a month after Germany had invaded the USSR – renewed diplomatic relations meant that the Soviets allowed formation of a Czechoslovak military unit on their territory.

In January 1942, Svoboda became deputy commander of the 1st Czechoslovak Independent Infantry Battalion.

Leaving for the front in the autumn, it first saw military action in March 1943 in Sokolovo, near Kharkiv.

Their success in slowing down the German forces led to the formation of the 1st Czechoslovak Independent Infantry Brigade, commanded by Svoboda. It fought hard on the Voronezh Front, and also participated in the Battle of Kyiv (November 1943).

In 1944, the Brigade was converted into an army corps; under Svoboda’s command, the corps took the Dukla pass and entered Czechoslovakian territory – which Svoboda had not been on since 1939.

In April 1945, the Communists set up a government in Košice; Svoboda was appointed Minister of National Defence. He then became Minister of Defence after the Prague Uprising and the reestablishment of Czechoslovakia.

In 1948, nearly the entire non-Communist part of the cabinet resigned in protest against the policies of Klement Gottwald; Svoboda, formerly seen as apolitical, did not. After the February coup, he joined the Communist Party.

Svoboda became Deputy PM in 1950, but was dismissed the following year as part of the purges of the time. He was sent to run a farm, then to prison; released after Stalin’s death, he was chosen (apparently by Khrushchev) to lead the Klement Gottwald Military Academy.

In March 1968, at the height of the Prague Spring, Alexander Dubček nominated Svoboda to replace Antonín Novotný as President of Czechoslovakia. As a war hero who had been punished during the purges, society viewed him relatively favourably.

However, when Warsaw Pact forces invaded in August, Svoboda was one of those forced to sign the Moscow Protocols, which ended the Prague Spring and the liberalisation of society, which now got delayed by over two decades.

In increasingly poor health, Svoboda resigned in 1975 and died in 1979.

He believed that his actions in signing the Moscow Protocols prevented thousands of people from suffering much, much more than they would have done had he refused.

Whether this was true or not, Svoboda’s lack of hardline communist learnings – and his past as a war hero – are surely why this embankment didn’t undergo a swift name change in 1990; indeed, he is still an honorary citizen of Prague, Plzeň, Brno and Ostrava.

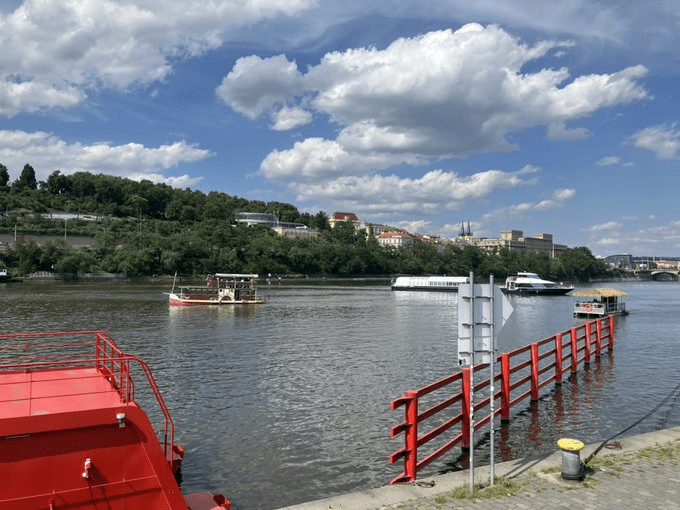

Nice views too.

Before we go (yes, this was another long one), we’ve got to give a special mention to the Ministry of Transport, originally (1927-32) built for the Czechoslovak Ministry of Railways (it still hosts the HQ of České Dráhy too).

It was here, on the night of 20/21 August 1968, that the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Czech Republic found out that Warsaw Pact forces had invaded, and issued a declaration rejecting this invasion.

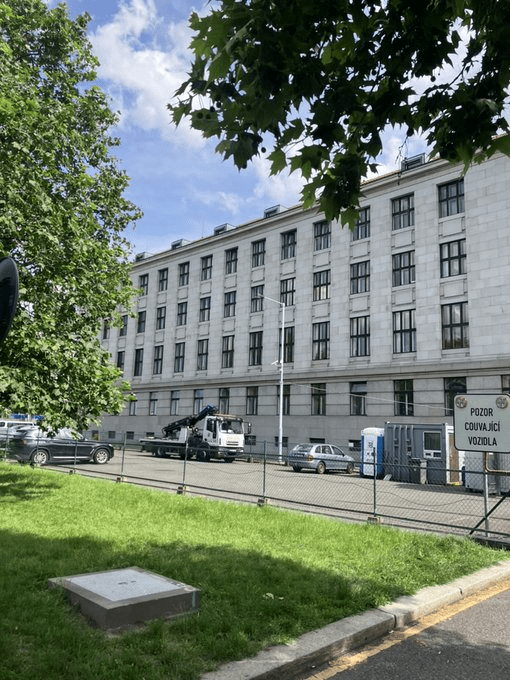

Also on the embankment, the Ministry of Agriculture was built in 1928 in neo-Classicist style; it’s quite imposing, but lacks the ‘quirks’ of the two ministries to its west (the Ministry for Industry and Trade was covered in several recent threads).

There’s something outside the Ministry that’s worth noting – but that’s on a different street, and, therefore, for a future post.

Leave a comment