Na Vítězné pláni (On the Victory Plain) already existed in the first half of the 20th century, but wasn’t given its name until 1993.

If you were ever a Czech schoolkid, you’ll be familiar with the Hussite Wars; if you weren’t, let’s take a trip back to 1420.

In March, Pope Martin V issued a Papal Bull, inviting all Christians to launch a crusade against the Hussites (take a look at https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/10/05/prague-1-day-169-husova/ for their origins).

Led by Sigismund – King of Bohemia, but categorically not a Czech or a Hussite – crusading troops had entered Bohemia by the end of April. Around the same time, Hussites forces founded the town of Tábor in South Bohemia.

After getting their hands on Hradec Králové, Team Catholic made their way to Prague, which was harder to conquer, especially after the decisive Hussite victory at Vítkov Hill in mid-July (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2022/12/04/prague-3-day-111-pod-vitkovem/).

Sigismund, sensing things weren’t going according to plan, was hastily crowned King of Bohemia at Prague Castle on the 28th, and, two days later, announced that the crusade was cancelled for now.

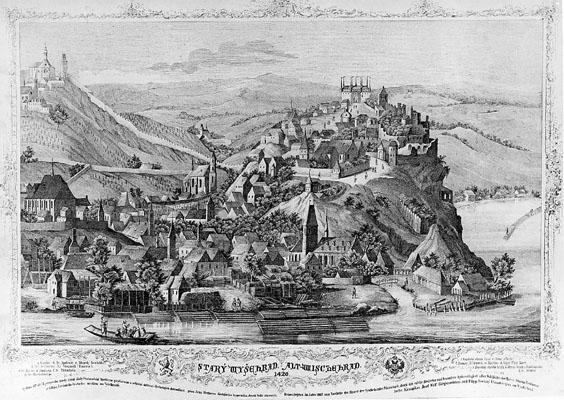

However, his troops still held the castles at Hradčany (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/02/prague-1-day-1-u-svateho-jiri-st-georges-square/) and Vyšehrad (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/08/26/prague-2-day-118-vysehradska/), meaning that a Hussite city had non-Hussite fortresses on either side.

In September, the citizens of Prague decided to besiege Vyšehrad, an operation that could be particularly beneficial, given that the fortress was on the route from Prague to Tábor. Thanks to reinforcements from the countryside, it was soon surrounded.

The Hussites set up their main camp at Pankrác, and Sigismund had clearly underestimated their strength, as he wasn’t in Prague at all when word reached him that his men at Vyšehrad were running out of water and food, and having to eat their own horses.

Sigismund started to make his way back to Prague on 28 October, having apparently recruited another 20,000 men. On the same day, the Vyšehrad garrison agreed to surrender to the Hussites on the morning of 1 November if Sigismund hadn’t delivered sorely-needed food supplies on 31 October. And, as it turns out, Sigismund didn’t begin to set out for Vyšehrad until the morning of the 1st.

When he arrived around three o’clock, he ordered his forces to attack around the Church of St Pancras, as well as from Podolí. The Hussites initially retreated, but, later, the tide turned: 1,500 of the crusading cavalry started to retreat, followed by other units.

Soon enough, Pankrác plain was covered with the bodies of Sigismund’s men, and, given that Sigismund hadn’t turned up until three in the afternoon – in November – it was a pretty short battle before the sun set. Thus ended the Battle of Vyšehrad on ‘Victory Plain’ (or Vítězná pláň – hence the name of the street).

The garrison at Vyšehrad surrendered; the Hussites looted the churches there, but spared the inhabitants. Meanwhile, news of Sigismund’s defeat soon made its way around Europe, and the first anti-Hussite crusade was over. That said, it would only be six months or so until the second one.

There’s a secondary school on the street, sharing a name with it.

Leave a comment