The road was built in 1931, and, until 1940 (and again from 1945 to 1978), it was named 1. listopadu – 1 November – in honour of the Battle of Vyšehrad in 1420: https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2025/02/01/prague-4-day-21-na-vitezne-plani/.

By May 1945, Bohemia and Moravia had been occupied by Nazi Germany for over six years. However, both Soviet and American soldiers had entered Czech territory in the spring.

On 24 April, Stalin announced that the Soviets would liberate Prague and the surrounding area. There were well-founded fears from, among others, Winston Churchill and Edvard Beneš, that this would subject the Czechs to long-term Soviet influence.

The Americans were more focused on taking military action in Germany and Austria – and were counting on Soviet support in Japan – so, on 1 May, President Truman announced that the US wouldn’t take part in the liberation.

Two days after Stalin’s announcement, the Soviets liberated Brno; six days later, on 2 May, they entered Berlin. Between these two events – on 30 April – Hitler had died and American troops had entered Munich.

The Soviets intended to enter Prague on 7 May; however, the domestic resistance had been planning their uprising for several months, despite a lack of soldiers and weapons.

It may also be useful to mention two earlier events in 1945: former Czechoslovak army officers had set up the Bartoš Command, which was supposed to oversee fighting in Prague, and the Alex Command, which was to direct insurgents in the suburbs.

Meanwhile, the Czech National Council – a union of domestic resistance organisations – had a military commission which was also preparing for an uprising (the Commands were unaware of the Military Commission, and vice versa).

Now, on to the 5th.

At 06:00, a voice on Czech Radio – that of Zdeněk Mančal – announced that ‘Je právě sechs hodin’ – ‘It’s exactly six o’clock’, in a mixture of Czech and German. Broadcasting in Czech had been forbidden for years.

At 08:00, an announcer was stopped from reading the news in German, and the content of the broadcast after that – the language and the music – was decidedly Czech.

That morning, the National Committee of Greater Prague was founded; at 10:30, it announced, via street radio, that the Third Reich was no more, and ordered those who were working for it to stop.

Czechs started taking German flags and signage down, replacing them with Czechoslovak flags and Czech signage. They also began arresting Germans; German soldiers retaliated with shooting.

Meanwhile, on Old Town Square (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/10/12/prague-1-day-190-staromestske-namesti-old-town-square/), the Alex Command met.

They received a copy of an alleged order from the Third Reich, decreeing that the Wehrmacht should hand Prague over to Czech forces. Fifty minutes later, it was announced that all Czech officers had to report to their garrisons.

The Bartoš Command met on Bartolomějská (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/28/prague-1-day-150-bartolomejska/), later establishing contact with the Czech National Council. The Bartoš and Alex Commands (eventually) agreed to be subordinate to the Council.

Around noon, the Bartoš Command had ordered that the Czech Radio building on (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2023/02/26/prague-3-day-161-vinohradska/) be secured, but it was guarded by SS patrols who began to search the building.

Half an hour later, Czech radio staff broadcast a call for the police, the army, and all good Czechs to help. Or, in other words, to participate in the Prague Uprising.

Locals, both armed and unarmed, didn’t hesitate to obey the call, and street fighting broke out around the radio building. The Germans in the radio building surrendered around six o’clock.

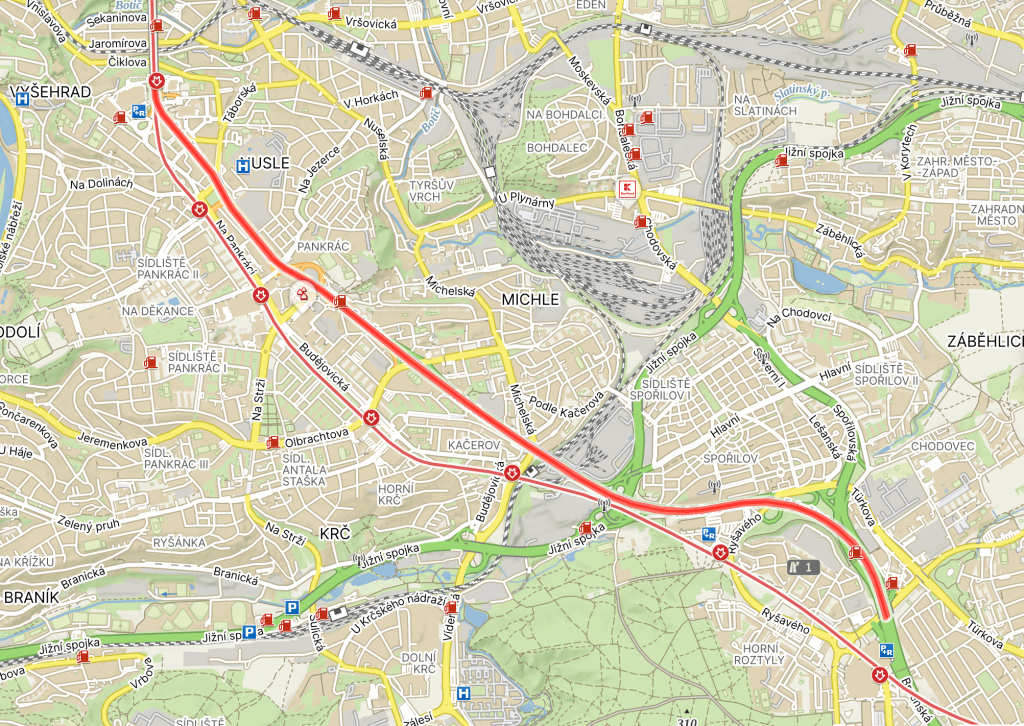

Fighting took place elsewhere in Prague too, especially at the main train stations and in both of central Prague’s town halls. The rebels managed to gain control of the City Telephone Exchange, Pankrác Prison, and almost all of Prague’s bridges.

By the end of the day, the rebels controlled most of Prague on the eastern bank of the Vltava, although the Germans still controlled much of the western side, including the airport.

While this street is only named after the first day of the uprising – and that’s all that I’m covering here, as other stories will surely come up in future posts – it lasted until 9 May, when Soviet troops entered the newly liberated city.

In those five short days, about 2,000 Czech civilians lost their lives, and you will see plaques dedicated to them all over the city, especially in Vinohrady.

Meanwhile, the failure of the Western states to liberate Prague reinforced what many had already felt when the Munich Agreement was reached in 1938: namely, that Western concern for Czechoslovakia was extremely limited. The Soviets wouldn’t take long to use this to their advantage.

Leave a comment