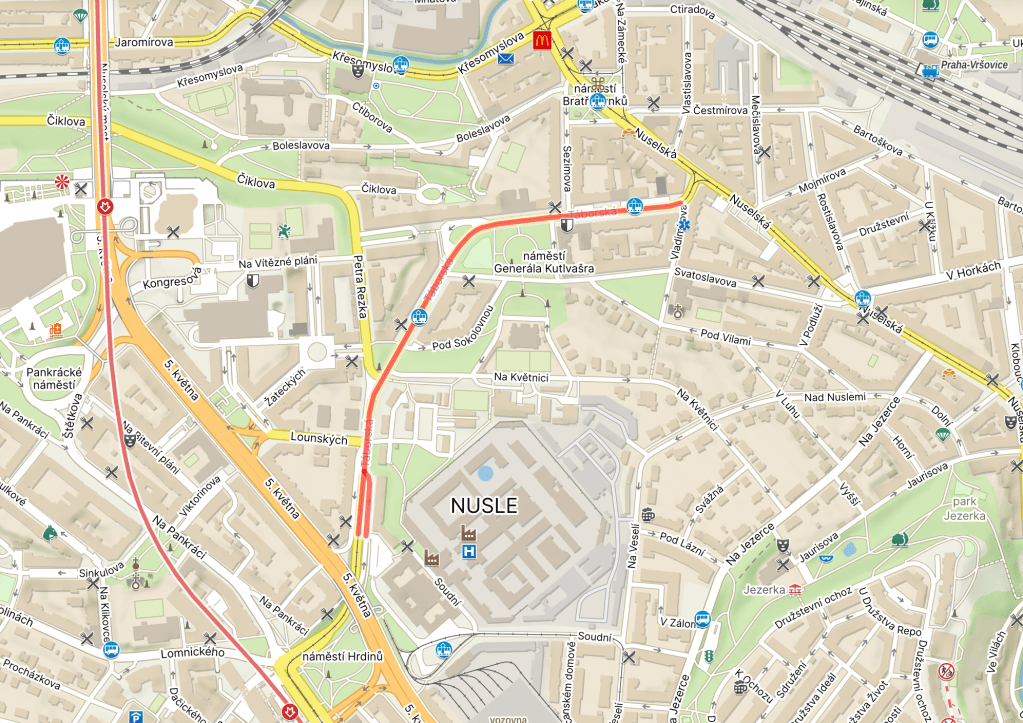

Originally, this was part of the road from Prague to České Budějovice and then on to Linz, and was therefore known as Linecká, Budějovická, or, reflecting its direct surroundings, Nuselská.

From 1900 to 1940, and again from 1945 to 1947, it was named Palackého – see https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/08/31/prague-2-day-145-palackeho-namesti/ to learn about Mr Palacký.

Tábor, population 34,000, is the second-largest town in South Bohemia.

There’s also a Mount Tabor in North Galilee; three out of the four Gospels state that this is where Jesus was transfigured and began to shine with rays of light (interpretation by Raphael).

Later on, in the Book of Judges, a battle took place at Mount Tabor between the Israelites and the Canaanites after a prophetess, Deborah, had summoned Barak, a military commander, to take ten thousand soldiers there.

Back in South Bohemia, archaeologists have proved that there was a settlement here in the 13th century, even though this isn’t backed up by contemporaneous written sources.

In the early 1270s, King Přemysl Otakar II (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2025/01/06/prague-4-day-6-otakarova/) made plans to create a new centre of royal power round here, but he died in 1278 and this never materialised.

Moving forward to the early 1400s, the Bohemian Reformation was underway. In the briefest terms, the Hussites – named after Jan Hus – wanted to reverse the moral decay of the Catholic Church and make it return to the Christian principles of poverty and modesty.

Hus was executed for heresy at the Council of Constance in 1415; wars between Hussites and Catholics would then take place on a regular basis from 1420 to 1434.

In the spring of 1420, many Hussites – already fans of mountain pilgrimages – decided to create a new ‘community of the righteous’, governed only by God’s law.

New arrivals were instructed to leave their belongings in the main square; these would then be distributed among the population, who were known as Taborites. However, this communism-before-communism was abandoned within a few months.

The town was led by four elected governors, and, from day one, had its own army, led by, amongst others, a certain Jan Žižka, who would give his name to an entire district of Prague (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2023/02/26/prague-3-day-150-zizkovo-namesti/).

The army looted property from nearby places to gain income, burned down churches and monasteries, and destroyed anything they believed to represent the evils of Catholicism.

In 1437, after years of war – which largely taught the Catholics that the Hussites couldn’t be defeated on the battlefield – Sigismund of Luxembourg, who had been crowned King of Bohemia in 1419 but whom the Hussites refused to recognise, recognised Tábor as a Hussite town.

However, Sigismund died in the same year, and, in early 1438, the Taborites rejected his successor, Albert II of Germany, who sent his troops to besiege the city. They lost.

Fourteen years later, the city would finally accept a King of Bohemia, specifically Jiří z Poděbrad; 1452 is considered the end of Tábor’s era as a place of Hussite rebellion.

Tábor would later be hit by bad luck – such as huge fires in 1532 and 1599 – and by punishment from Catholic overlords – and after it rose in rebellion against Ferdinand I, he proceeded to deprive it of all the land it owned.

However, once rebellious, always rebellious, and there was a gap of almost a year between the Habsburg victory over the Hussites at Bílá Hora (December 1620) and the moment Tábor surrendered (November 1621). Again, there were punishments, and inhabitants were forced to convert to Catholicism.

In the 17th century, Tábor became a major location for the crafts industry; it was elevated to a ‘regional city’ by Maria Theresa in 1750.

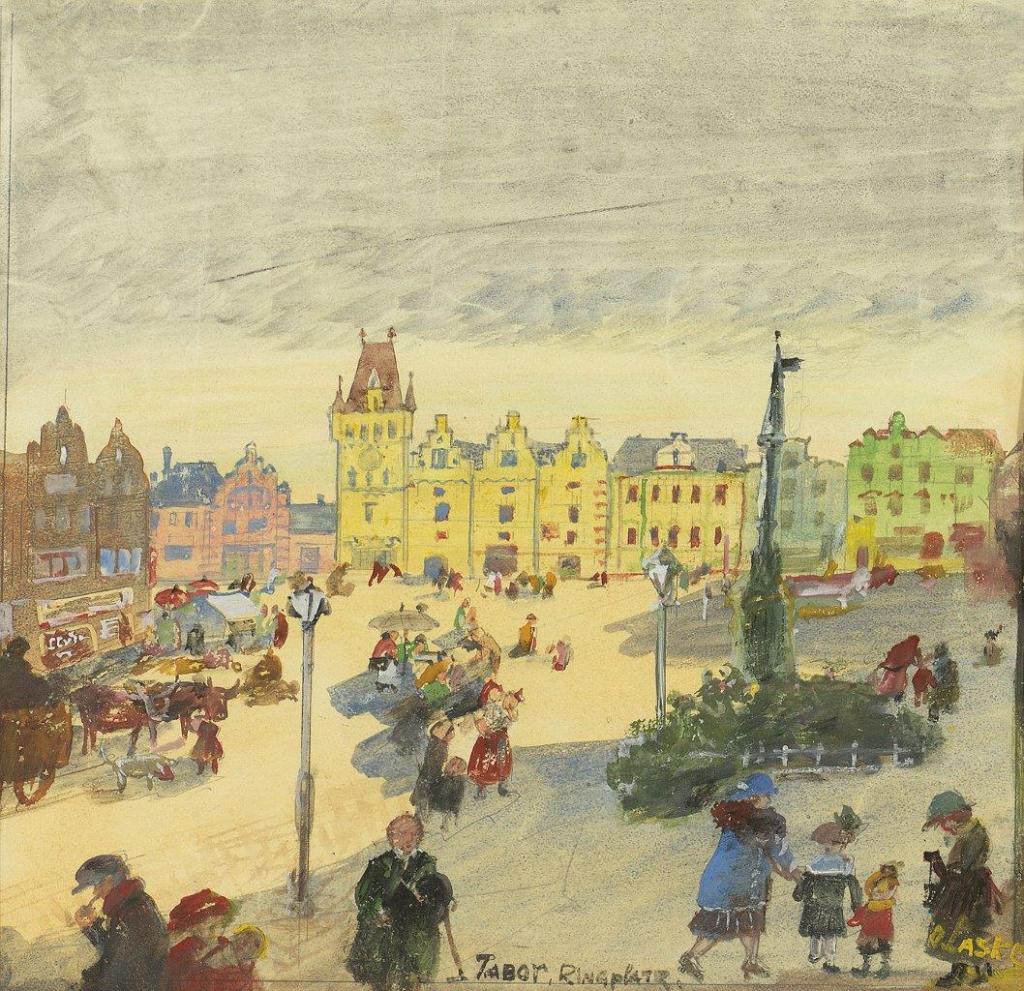

Here are two early photos of the city.

In 1862, the first Realgymnasium (secondary school) in Bohemia in which the main language of instruction was Czech was opened in Tábor.

It was also in Tábor that Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, entering a newly independent Czechoslovakia – as its president – stopped on his way to Prague. He made a speech stating that ‘Tábor je náš program’ – ‘Tábor is our programme’.

This was particularly symbolic given that Masaryk was not a Catholic, and Czechoslovakia had finally thrown off the shackles of the Austrian regime which had forced recatholicisation of Bohemia in the 1620s.

Unsurprisingly, Tábor remains a popular tourist attraction. Painting by Oskar Lake.

Leave a comment