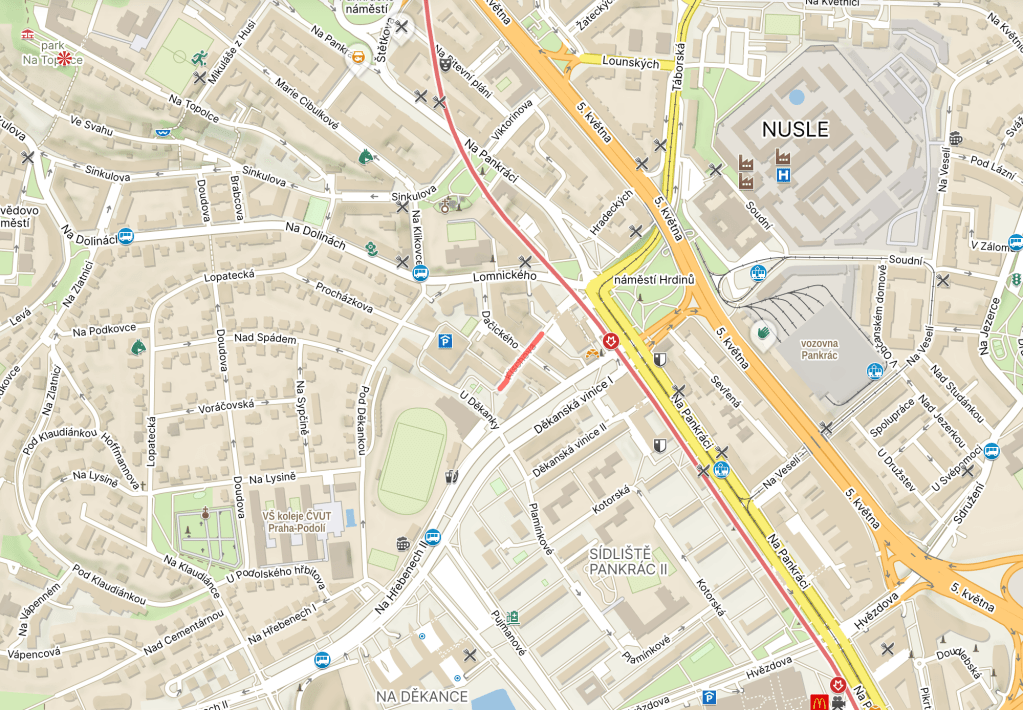

Kischova was built in 1900.

It was originally named Třebízského, after the historical novelist Václav Beneš Třebízský, who still has a street named after him in Vinohrady: https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/01/27/prague-2-day-17-trebizskeho/.

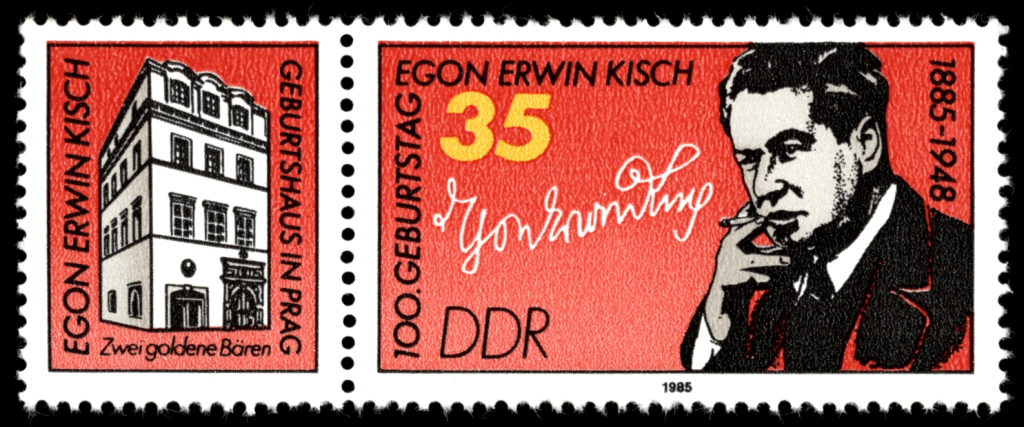

Egon Erwin Kisch was born into a Jewish family in 1885, and grew up on Melantrichova in Prague’s Old Town, where his father, a cloth merchant, ran his shop (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/10/14/prague-1-day-194-melantrichova/).

Home-schooled, he then went to school on Michalská (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/10/07/prague-1-day-173-michalska/), and then on Panská (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/23/prague-1-day-139-panska/).

After transferring to the German Realschule on Mikulandská (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/14/prague-1-day-102-mikulandska/), he studied philosophy at the Technical University in Prague, but switched to current-day Charles University after one term.

Clearly preferring the autodidact route, Kisch left university, and taught himself stenography, several languages and the art of journalism. In 1906, he became a reporter for Bohemia, a German-language Prague newspaper.

From 1910 to 1911, he had a regular column in Bohemia called Prager Streifzüge (Prague Excursions). He also became an expert in the Prague underworld; his only novel, Der Mädchenhirt (The Girl Shepherd, 1914) drew on what he had learned.

Key journalistic achievements at this time included an interview with Thomas Alva Edison (1912) and the uncovering of a spy scandal arising after the death of Alfred Redl, a military officer, in 1913.

Kisch moved to Berlin in that year, and started working at the Berliner Tageblatt, but 1914 brought World War One which, in turn, meant Kisch went to serve in the Austrian Army, initially in Serbia, later in Russia.

After getting injured on the Russian front, Kisch was declared ‘unfit for field service’, and served as a censor in Hungary, where he befriended soldiers who held pacifist and anarchist views.

In 1917, Kisch asked to be transferred to the Austro-Hungarian War Press Headquarters in Vienna, where, in early 1918, he organised a general strike. The authorities decided it was time to put him back into military service.

Kisch deserted and returned to Vienna in October 1918, just before the war ended, and, in November, played a key role in a failed left-wing coup in the city. He joined the Austrian Communist Party in the following year.

Not being the most popular person with the Austrian authorities, Kisch returned to Prague in 1919, then moved back to Berlin in 1921, staying there until 1933.

He worked for multiple newspapers, also becoming the Berlin correspondent for Lidové noviny, and gaining a reputation for his travel journalism – in the 1920s, he went to, and reported on, the Soviet Union, the Maghreb, the USA and China.

A volume of his travel reports was published in 1924, and was called Der rasende Reporter (The Racing Reporter) – and this nickname stuck. Among those he interviewed on his travels were Maxim Gorky, Charlie Chaplin and Upton Sinclair.

A bit closer to home, Kisch also wrote about his experiences serving in the Prague Corps, Prague’s Jewish community and crime in the city of his birth.

On 27 February 1933, the Reichstag in Berlin was set on fire. The next day, Kisch was arrested on suspicion of high treason. On 11 March, he was deported from Germany. In 1934, he moved to Paris.

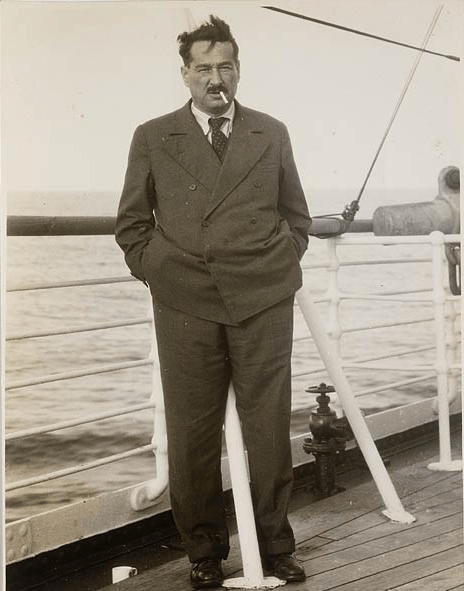

In 1934, Kisch travelled, by ship, to Australia as a delegate of the All-Australian Congress Against War and Fascism. He was denied entry at Fremantle due to his communist activity.

The ship travelled on to Melbourne, where Kisch jumped from the ship onto the quay, breaking his leg. Put back on the ship, he was taken off it when it arrived in Sydney, and was sentenced to three months’ hard labour (but was also released on bail).

The Australian left protested loudly, and accused Australian Attorney General (and eventual PM) Robert Menzies of being a Nazi sympathiser. Kisch was allowed to remain in the country, inevitably publishing a book about his experiences there.

In 1937 and 1938, Kisch went to Spain (he’s on the left in the pic below), then ravaged by the Civil War; once the Munich Agreement was signed, he was unable to return to Czechoslovakia, and, when World War Two broke out, the French authorities placed him under police surveillance.

At the end of 1939, Kisch managed to get to the United States, where, after several days on Ellis Island, he briefly settled in New York. In mid-1940, his wife Gisela arrived, and they moved to Mexico City, which had a vibrant German expat community.

In March 1946, Kisch returned to Prague. His two surviving brothers (another brother had died during WW1) had died during the War, one of them at Auschwitz.

Kisch became active in the Czechoslovak Communist Party, even though many of his German-speaking Prague friends were, around this time, forced out of the country.

Planning to write a book about the liberated Czechoslovakia, Kisch suffered two strokes in quick succession, and died in March 1948 at Kateřinská (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/08/28/prague-2-day-128-katerinska/). He’s buried at Vinohrady Cemetery.

The German magazine Stern launched a prize for outstanding journalism in 1977; it was named after him, holding that name until 2005: https://www.stern.de/kultur/buecher/themen/egon-erwin-kisch-preis-4128854.html.

Leave a comment