Originally published on X on 29 October 2023.

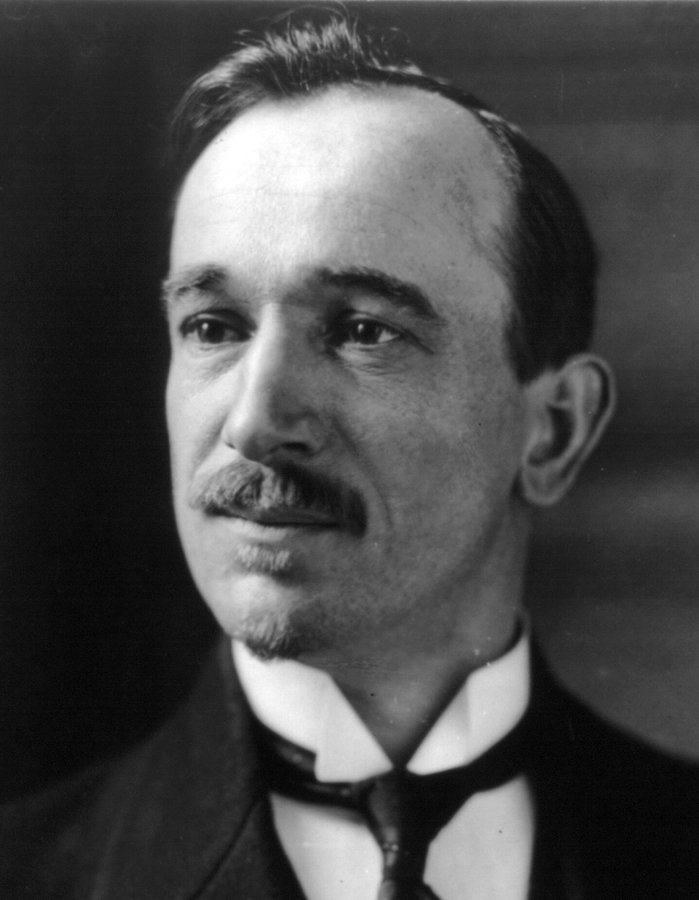

Eduard Beneš was born as the tenth of ten children in Kožlany, near Plzeň, in 1884. He attended the gymnasium in Vinohrady (on Londýnská – https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/03/03/prague-2-day-41-londynska/), then studying at Prague University, followed by the Sorbonne, Berlin and Dijon.

In Paris, he became engaged to Anna (later Hana) Vlčková, and changed his own name to Edvard.

In 1908, Beneš completed his studies in Dijon with a thesis on the problems faced by the Czechs in the Austro-Hungarian Empire; he graduated from Prague University the following year despite the authorities somewhat wishing he’d chosen a different topic to write about.

In the same year, he and Hana got married in the Church of St Ludmila on Náměstí Míru (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/03/03/prague-2-day-42-namesti-miru/).

After graduation, he taught at the business academy, started to study law, and lectured as an associate professor at Prague University’s Faculty of Arts.

When World War I started, Beneš founded Maffie, a secret organisation aiming to overthrow the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Going into exile in France 1915, he collaborated with both Tomáš Masaryk and Milan Rastislav Štefánik.

Their cooperation would lead to the founding of the Czechoslovak National Council (in 1916) and the Czechoslovak Legion (in 1917).

When Czechoslovakia became independent in 1918, Beneš was appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs, although he didn’t return to the country until almost a year later, having represented Czechoslovakia in the negotiations that would lead to the Treaty of Versailles.

Beneš also helped to found the League of Nations, serving as a member of its council, its Vice-President, and, ultimately (1935-6), its President. He would also continue to hold his role as Minister of Foreign Affairs until 1935, with a brief stint as PM from 1921 to 1922.

In 1935, Masaryk abdicated as President of Czechoslovakia, and Beneš took his place. This was also the year in which two thirds of Sudeten German voters voted for the pro-Nazi Sudetendeutsche Partei.

In 1938, the SdP demanded autonomy for the Sudetenland under the ‘Karlsbad programme’; Beneš’s attempt at a compromise (under the ’Third Plan’: less autonomy than demanded, but still not a bad amount) was rejected, and the British government recommended that Beneš give way.

Beneš’s “Fourth Plan”, presented in September, would’ve created a Federal Czechoslovakia; the SdP rejected this too.

On 30 September, Germany, Italy, France and the UK signed the Munich Agreement, providing for the Sudetenland to be annexed by Germany.

Britain and France told Beneš that they wouldn’t assist militarily if Germany invaded Czechoslovakia – which contradicted a military agreement signed between Czechoslovakia and France in 1925 – and Beneš gave in. He resigned on 5 October and was replaced by Emil Hácha.

Beneš went into exile, first to Britain, then to the US, where he taught at the University of Chicago. He then went back to London in 1940, forming the Czechoslovak government in exile and becoming its president.

After WWII, when Czechoslovakia was restored, Beneš was, once again, confirmed as President.

He signed the Beneš decrees, the result of which was the expulsion of nearly all Germans and Hungarians on Czechslovakian territory, many of whose families had been here for centuries.

The decrees have never been repealed, and remain a source of tension to this day.

In 1946, the Communists won the elections; Beneš, believing himself to have a good relationship with Stalin, thought Czechoslovakia could remain a multi-party democracy. The February 1948 coup d’état would prove otherwise.

Already in ill health by that time, it would’ve been hard for Beneš to put up a fight. He resigned as president in June 1948, and the media started a hate campaign against him that summer. He would die of natural causes at his villa in Sezimovo Ústí in September, aged 64.

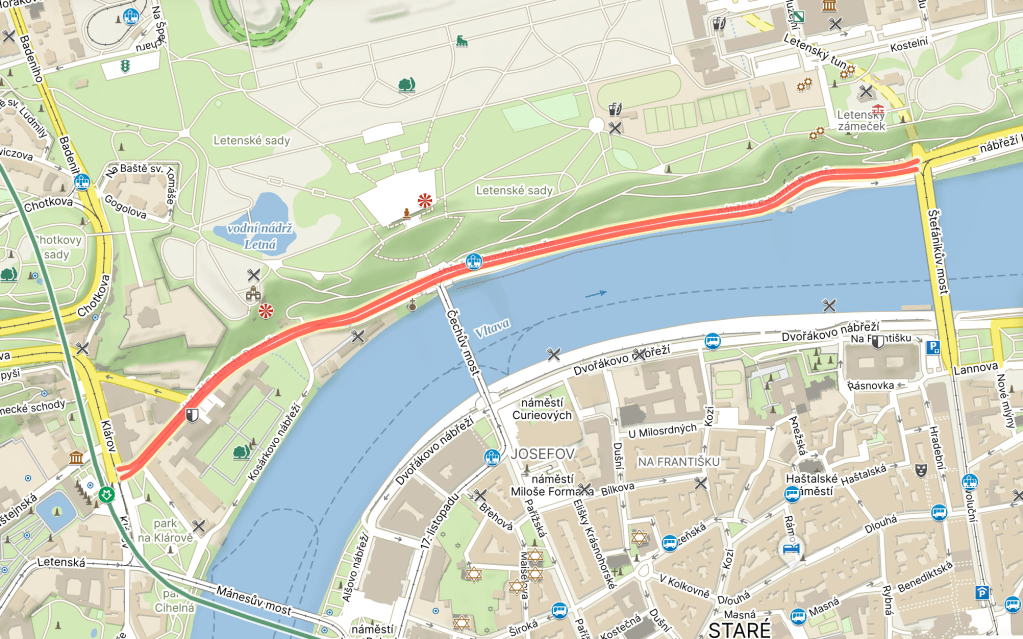

The Embankment includes the Office of the Government of the Czech Republic / Úřad vlády České republiky, housed in the Straka Academy. Its gardens are a very nice place to sit when they’re open.

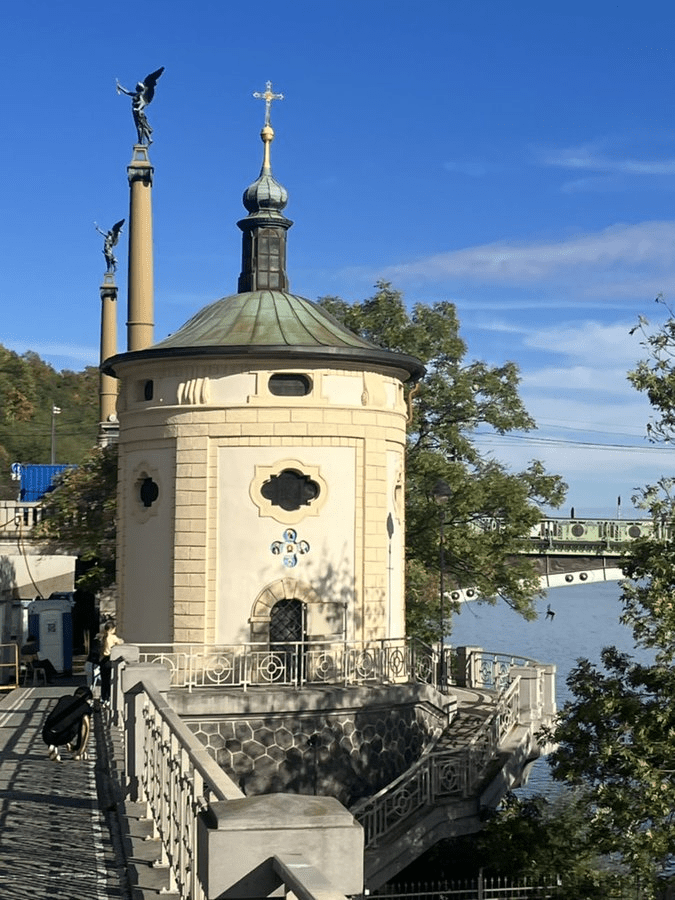

And a bit further on, there’s the Chapel of St. Mary Magdalene, and, if you stand around here, you’re in the tiny part of Holešovice that’s in Prague 1 rather than Prague 7.

Leave a comment