Originally published on X on 7 January 2024.

Until 1781, there was a moat here, which had the somewhat inconvenient effect of separating the Old Town and the New Town. Therefore, it was decided to fill the ditch and create a street in its place.

Originally called Nové Aleje (New Avenue), this later turned into V nových alejích (In the New Avenue(s)), and then into V stromořadí (In the Avenue), and *then* into Uršulinská after the Ursuline convent and church (see https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/14/prague-1-day-103-vorsilska/).

Between 1839 and 1841, a chain bridge was built to the west of the avenue (see https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/12/prague-1-day-90-most-legii-legion-bridge/), and so, because apparently enough renaming hadn’t happened by this stage, the road became known as U Řetězového mostu.

Then, after 1870, it was named Ferdinandská, after Ferdinand V ‘the Benevolent’ / ‘Dobrotivý’, who had abdicated the Habsburg throne in 1848 and lived out his remaining years in Prague Castle. The name shifted slightly to Ferdinandova třída around 1900.

The current name was introduced in 1919, and has been used ever since (except during the Nazi occupation, when it was called Viktoria).

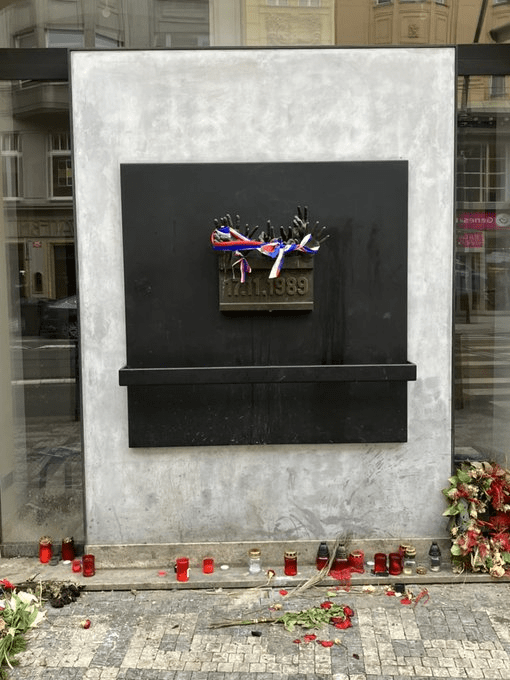

On 17 November 1989, Národní was the scene of a brutal crackdown on demonstrators by the riot police.

600 people were injured, some of them seriously; only about 30 people ended up being charged, with many of them getting suspended sentences: https://www.irozhlas.cz/veda-technologie/historie/17-listopad-1989-vysetrovani-demonstrace-serial_2211201117_afo.

As well as those crucial moments in Czech history, there’s so much to see on Národní. Let’s go for a walk (please forgive me for skipping the theatre and the Ursuline convent/church, both of which are discussed in recent threads).

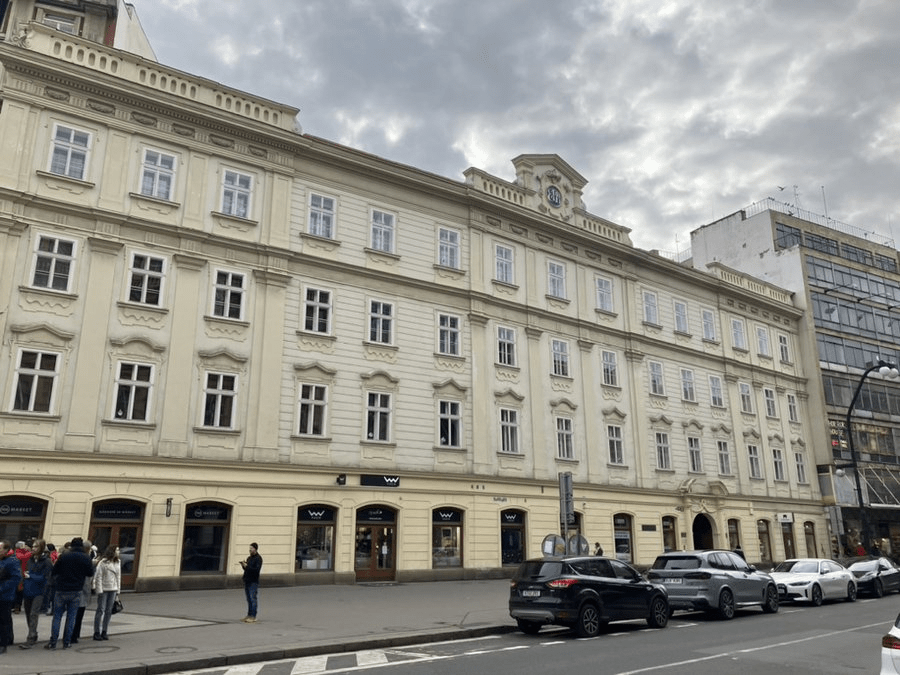

Lažanský Palace was built between 1861 and 1863, and, in its early days, was lived in by Bedřich Smetana. You may well be familiar with the cafe that was opened in the building in 1881 – Cafe Slavia.

Other parts of the building are used by FAMU.

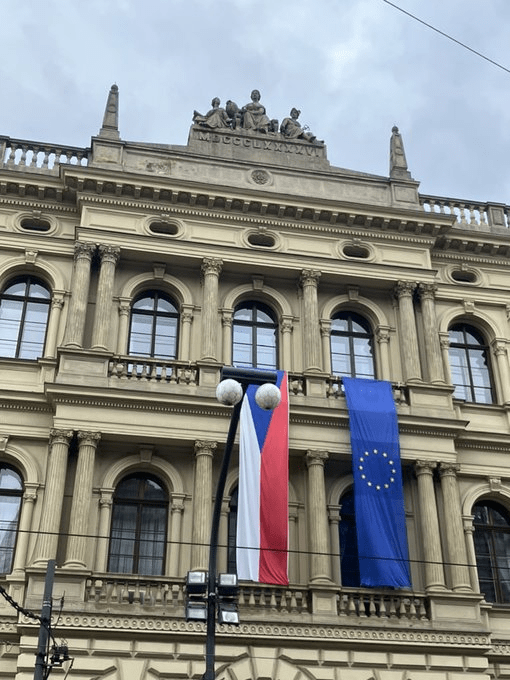

Next door to the palace, and built around the same time (1858-62) for the Spořitelna česká bank, number 3 has hosted the Czech Academy of Sciences since 1994.

At number 7, Pojišťovna Praha (the Prague Insurance Company) was built between 1906 and 1907, and is owned by the Center of Joint Activities of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic. Nice bookshop in there too.

Continuing the (freaking awesome) art nouveau theme, Topič House is at number 9. It was built as part of the František Topič Publishing House and used to host Topič Salon, once the longest-running private art gallery in Prague.

At number 25, Palác Metro was built in 1870 and given an overhaul between 1922 and 1925. Nowadays, it includes three theatres and, because I don’t want to paint an idealised picture of Prague, a KFC.

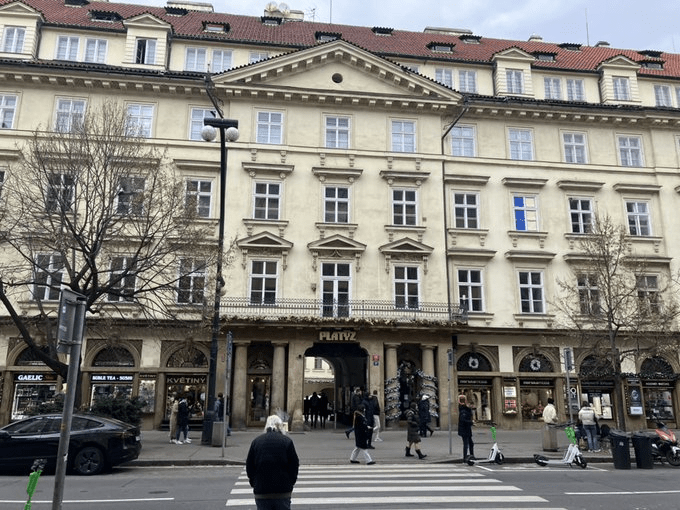

At number 37, Palác Platýz has a much longer history than most buildings here – back to 1347, though obviously not in its current form. Nice courtyard.

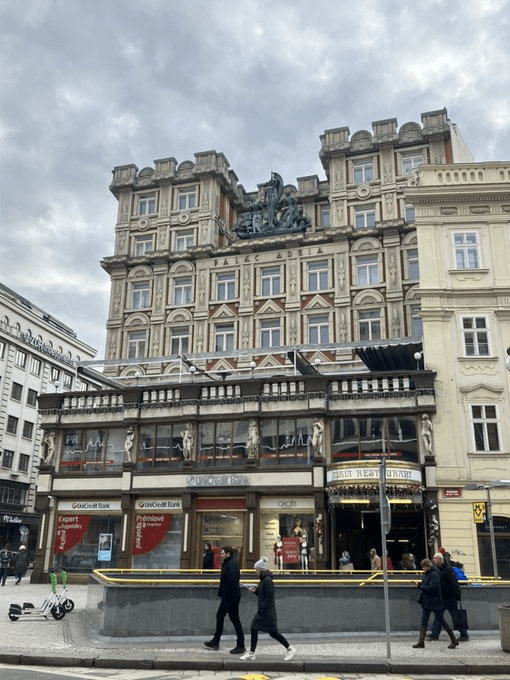

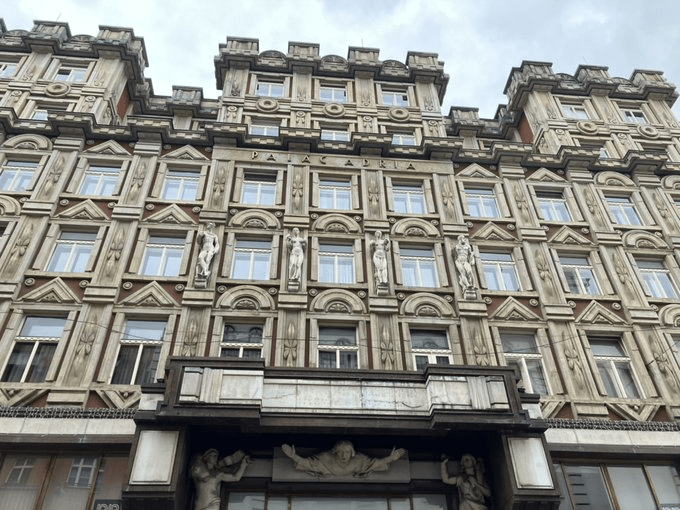

Crossing the road, we come to Palác Adria, one of those buildings that could be voted the best building in the world and still be underrated. It was built in 1924 and its style is apparently known as ‘Rondocubist’.

Since 1998, it’s hosted Divadlo Bez zábradlí, which, when it was founded in 1990, was the first privately-owned theatre in the country.

WHAT A BUILDING THOUGH.

Turning back towards the river, Palác Porgesů z Portheimu (1762-76) has been owned by the Prague Gas Works since the 1940s.

While Palác Chicago (1927-8) was, at the time of building, one of the most cutting-edge buildings in Prague; it was fitted out with facilities which were meant to emulate those of American skyscrapers.

The Máj shopping centre (1972-5) is known for being: a) incredibly 1970s; b) the scene of a multi-storey Tesco when I first visited Prague in 2005, a store so big that it had a boomerang section; c) briefly a Kmart in the 1990s; d) under reconstruction.

Palác Louvre was built around the turn of the 20th century, replacing an old riding stable. It’s best known for its eponymous cafe, which was one of Kafka’s favourite hangouts and reached the peak of its popularity in the 1920s and 1930s.

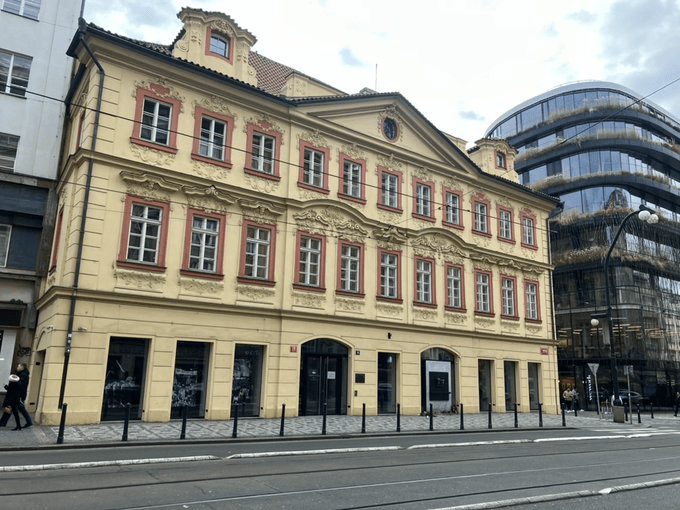

Schirdingovský palác (renovated in 1752) is the home of the Czech Bar Association. It’s most famous for its plaque commemorating the Velvet Revolution, as this is the spot where the most brutal police beatings took place.

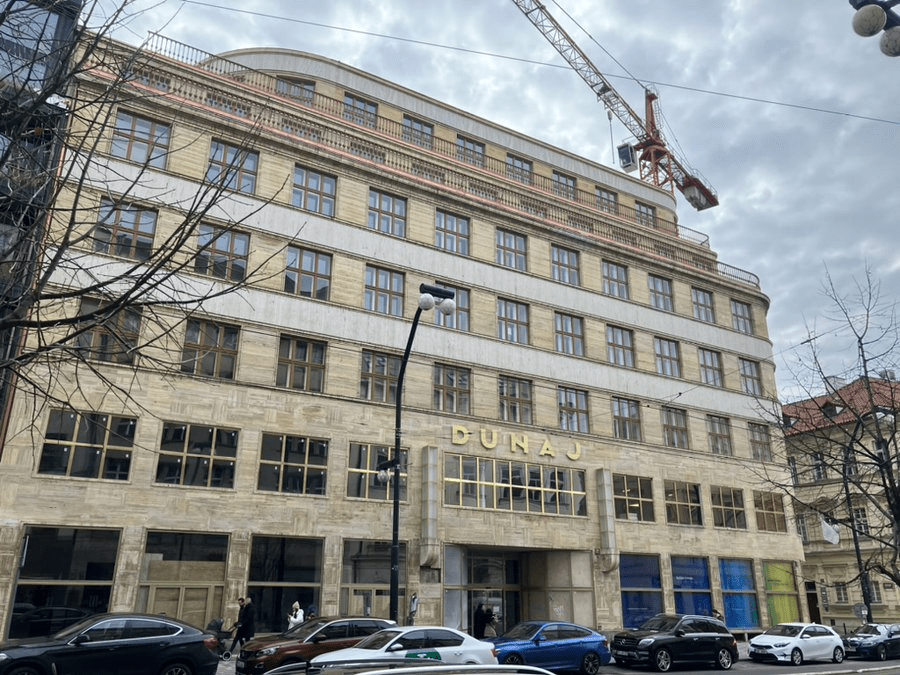

And finally, Palác Dunaj (Danube) was opened in 1930, and, during Communist times, hosted the Cultural Center of the GDR. Having hosted the British Council in the 1990s/2000s, it’s recently been converted into upmarket office space, and this is due to open in the next few weeks.

If there’s one thing I love about writing these posts, it’s the opportunity to walk down a street you’ve walked down a million times and see all these things you’ve never really looked at before. It’s kind of like falling in love with someone all over again.

Leave a comment