Originally published on X on 9 April 2024.

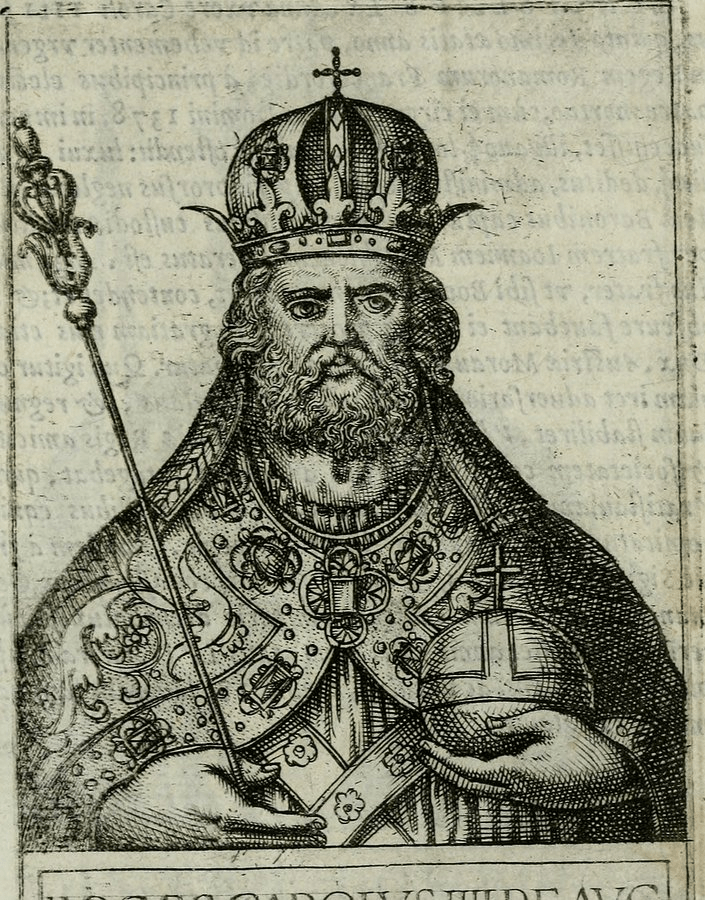

Charles/Karel/Karl was born in 1316, as the son of John of Bohemia and his wife Elizabeth.

Because these family trees aren’t confusing enough, his birth name was actually Václav, but he chose the name Charles at his confirmation.

In 1323, his father sent him to France, where he got an excellent, multilingual education.

His father also arranged for him to marry Blanche de Valois, a cousin of Charles IV of France (as opposed to Charles IV of Bohemia. This isn’t getting easier).

Having gained experience of battle at his father’s side in 1331, Karel was persuaded to move back to Bohemia, as his father was away a lot and was also losing his eyesight.

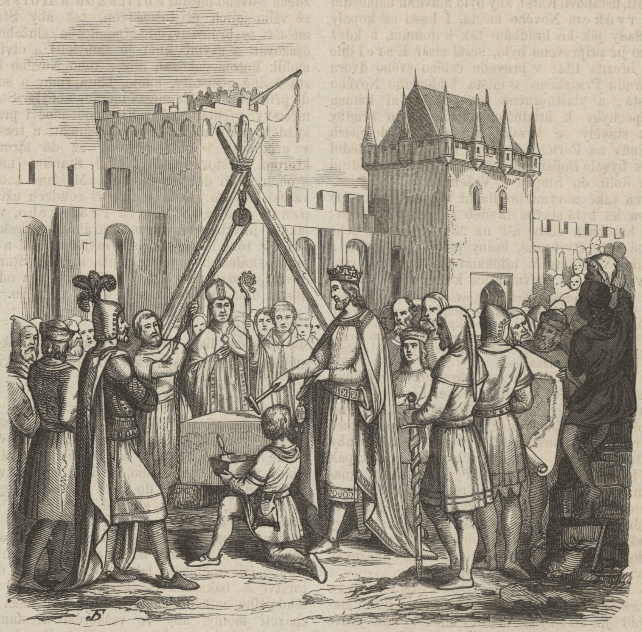

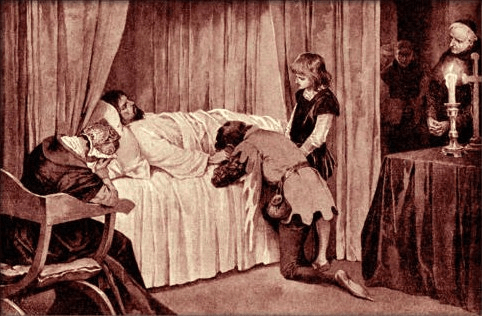

He returned in 1333 (here he is being welcomed at Újezd) and was named Margrave of Moravia.

Charles would soon prove to be a more energetic, authoritative and popular leader than his father, which is presumably what no father ever wants to hear.

Support from Pope Clement IV – a former teacher and confidant – enabled the promotion of Prague from bishopric to archbishopric in 1344.

But the Pope’s support would come in even more handily in 1346, when Clement supported Charles’ election as King of the Romans (and of Germany), replacing Louis IV (the Bavarian), who Clement seriously disliked.

Later that year, John would die at the Battle of Crécy, and Charles also became King of Bohemia, a role he’d kind of being playing for the last thirteen years anyway. He’d also become Holy Roman Emperor in 1355.

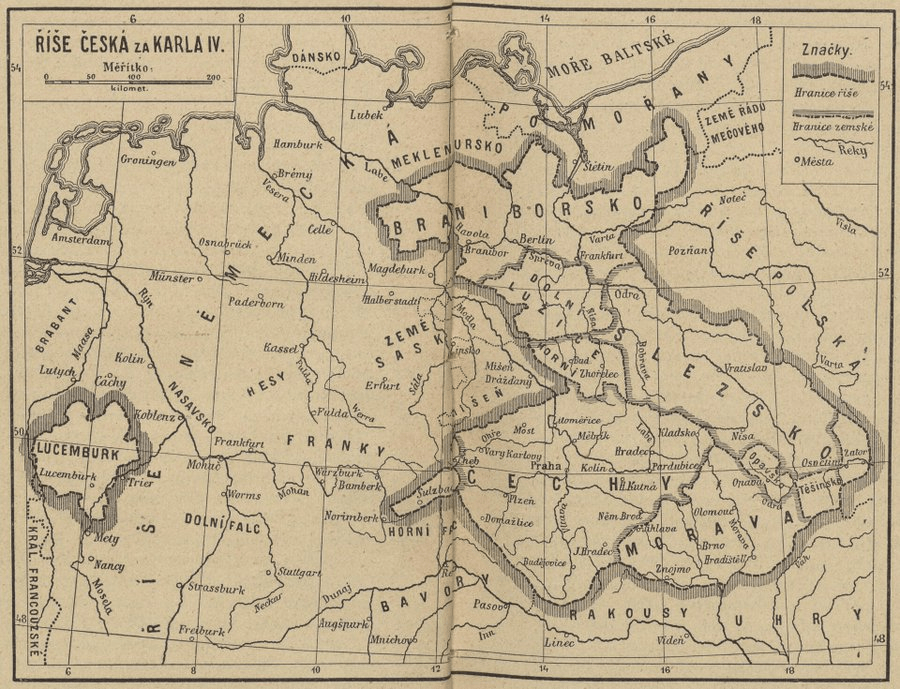

Charles made Prague his home, and really worked on turning it into the centre of the empire. Without him, we wouldn’t have the New Town, Charles Bridge, Charles University (the region’s first), and much more besides.

Beyond Prague, Charles was also successful in increasing the size of the Bohemian crown lands, annexing Upper Lusatia, Lower Lusatia, and, ultimately, Brandenburg.

However, this would be accompanied by family upsets – his first wife, Blanche de Valois, died in 1348. His second wife, Anne of Bavaria, died in 1353, and his third, Anna von Schweidnitz, in 1362.

His fourth wife, Elizabeth of Pomerania, would outlive him.

While his relations with the nobility were generally good, his attempts to codify Bohemian Law (in the Maiestas Carolina, written in 1350) were met with resistance, and by 1355 he’d given up on them.

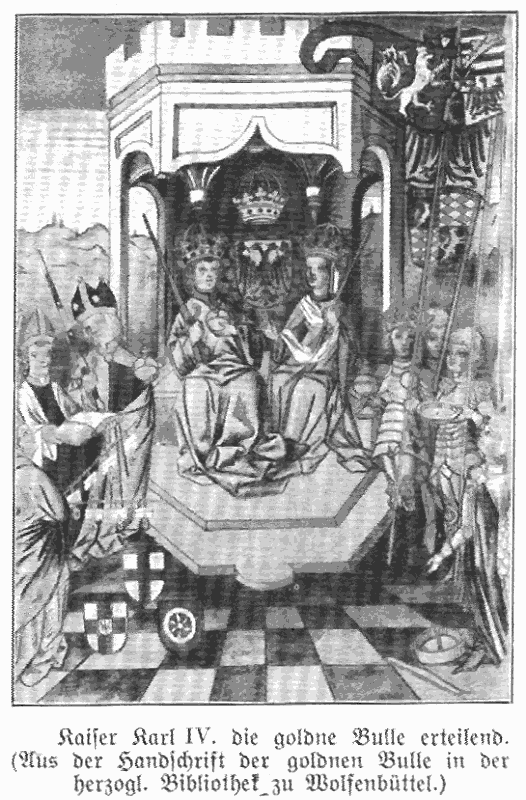

A year later, however, his Golden Bull, which set much of the constitutional structure of the Holy Roman Empire, including the system for election of its rulers, was adopted successfully.

Charles would also find time to write an autobiography, Vita Caroli, as well as other works.

He died in 1378 and was buried in Prague. In 2005, he was voted the greatest Czech ever in one of those shows that every country seemed to have around that time.

He’s on here too.

This leaves a lot out, obviously, but I get the feeling that a lot of the left out stuff will be used in future threads.

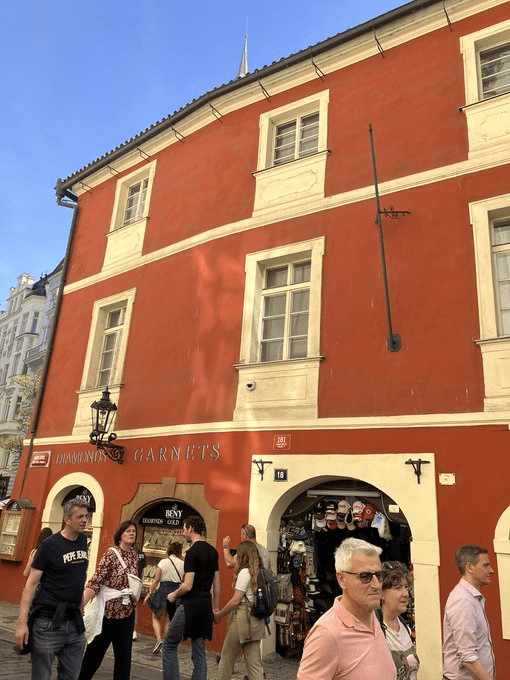

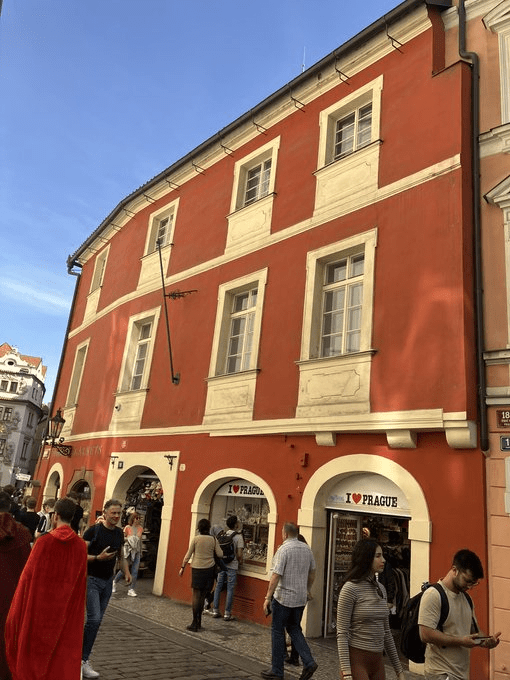

But we’re not done yet, because this street has major footfall (it was on the Royal Route back when there were royals, and is an inescapable part of the tourist route now that there are tourists).

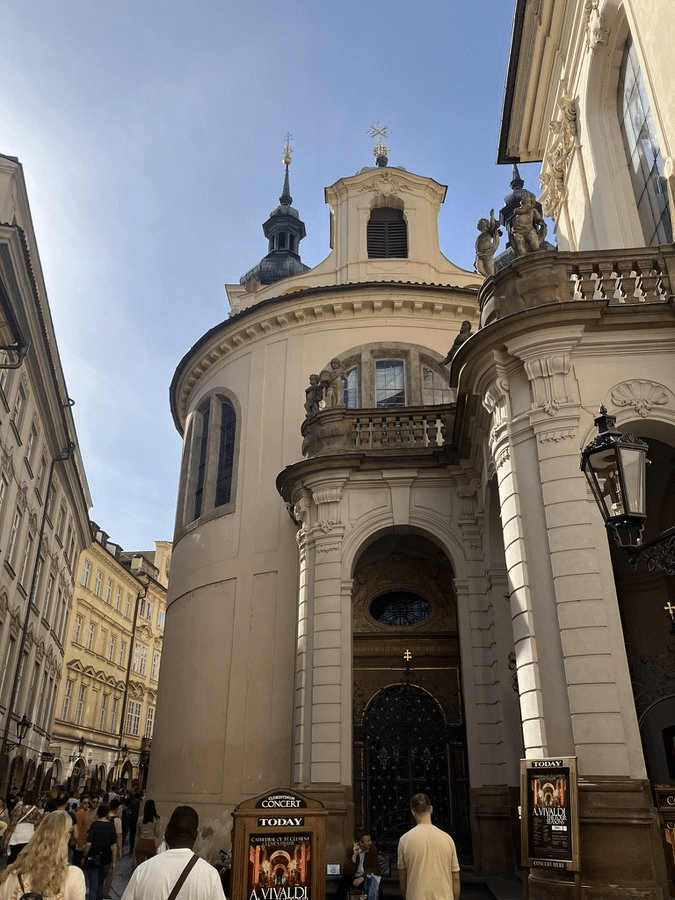

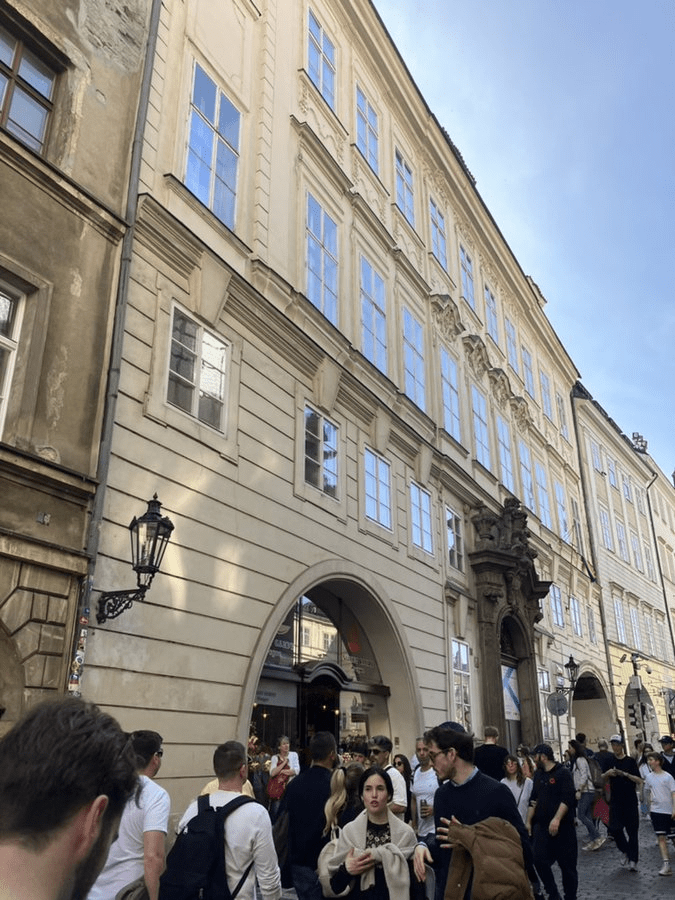

Starting by Charles Bridge, the Church of the Most Holy Salvator was the Jesuits’ seat in Prague when they were a thing.

Whereas the Chapel of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary – or Vlašská kaple – was the spiritual home of Prague’s Italian community (see https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/08/prague-1-day-31-vlasska/ for a language lesson).

And then there’s St. Clement’s Cathedral, the cathedral of the Apostolic Exarchate of the Greek Catholic Church in the Czech Republic. (Note: while writing this, I developed mild nerves that this might be the wrong building, but I’m posting it anyway)

All of these form part of the Klementinum, the largest complex of buildings in Prague after the Castle. It used to be a Jesuit college (1622-1773), and is now administered by the National Library of the Czech Republic.

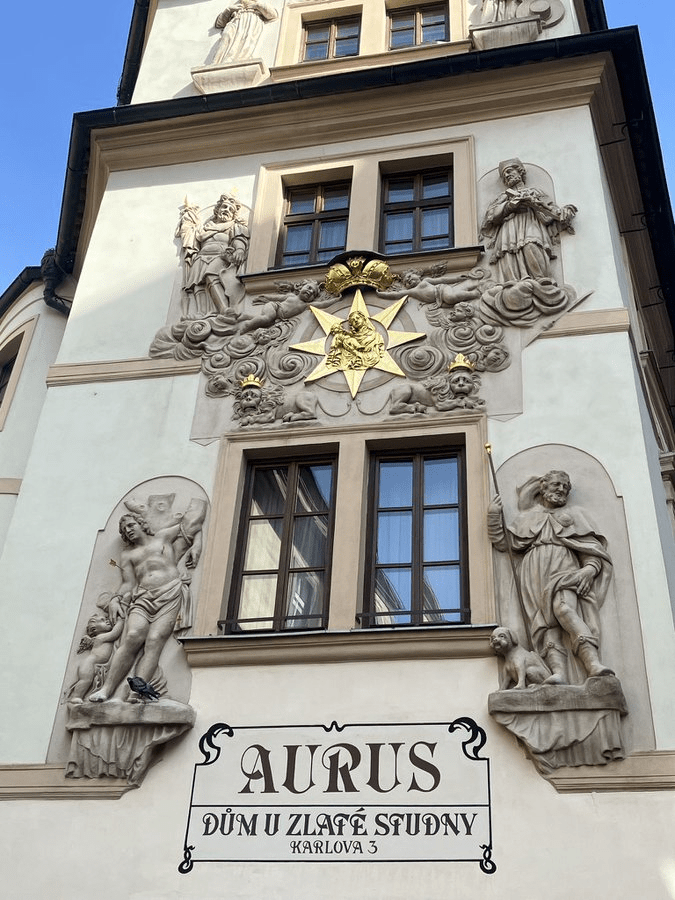

Non-Klementinum highlights of Karlova include U Zlatá studně (The Golden Well), now a hotel. On its façade, you can see Saint Wenceslas and John of Nepomuck, as well as two plague patrons and, on the top floor, Jesuit patrons.

At the turn of the 1700s, the owners added these decorations to show their gratitude for surviving a plague epidemic.

While, in 1714, U Zlatého hada (The Golden Snake) was apparently the location of Prague’s first cafe. A few more have opened since.

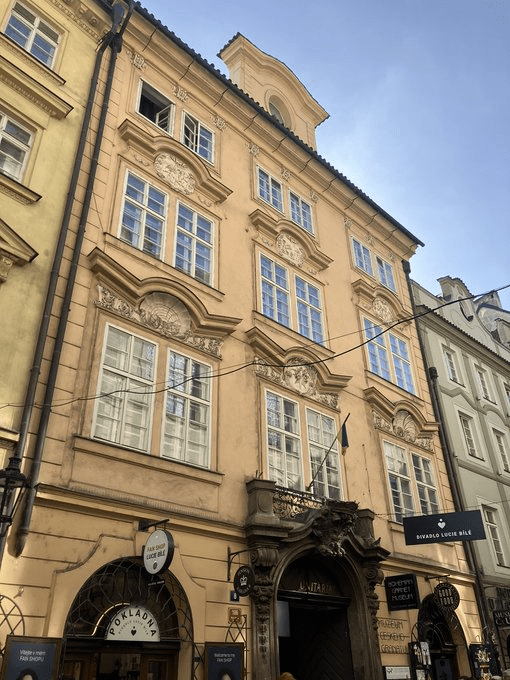

Colloredo-Mansfeld Palace is where, in 1620, the royal council of Frederick V of the Palatinate met for the last time after the Bohemian army’s beyond-disastrous showing at the Battle of Bílá Hora.

While Pöttingovský palác is currently home to Divadlo Ta Fantastika, a repertory theatre owned by Lucie Bílá (stop press: she’s gone and named it after herself now).

Leave a comment