Originally published on X on 24 and 25 January 2024 (it’s a two-partner).

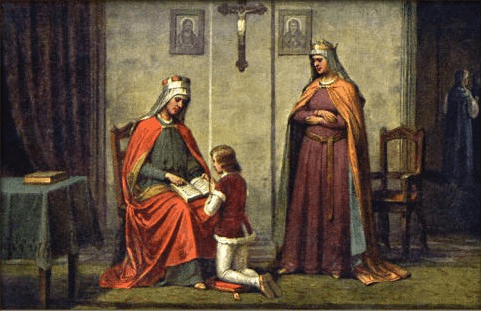

Václav (Wenceslas, as in ‘Good King’) was born around 907, the son of Vratislav (Wrocław-founding) and Drahomíra (pagan; murderous), and the granddaughter of Ludmila (Christian; victim of said murderousness; later saintly) and Bořivoj (the first verifiable Czech leader).

He became Prince of Bohemia while still in his teens, around 925. His reign had the typical features of the time, i.e. rivalry with Saxony which ended up with Václav promising to pay tribute to avoid Bohemia being raided (again).

He also decided to strengthen the Bohemian state, and the role that Christianity played within it. He therefore founded St Vitus Church at Prague Castle, predecessor of maybe the best-known building in the country.

However, submissiveness to Germans and introduction of a whole new religion didn’t sit well with many, including Václav’s brother Boleslav, who arranged for Václav’s murder in Stará Boleslav (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2023/12/23/prague-3-day-180-boleslavska/).

It’s accepted that this happened on 28 September – now also Czech Statehood Day – but we don’t know if it happened in 929 or 935.

In any case, by the end of the century, Václav had been beatified and was henceforth regarded as a key fighter for the national cause.

Now onto the square.

As mentioned in every other post of late, Charles IV founded Prague’s New Town in 1348. A new town requires a new market, and one of the main ones was set up here, on what became known as the Koňský trh (Horse Market).

It’s hard to imagine now, but, even 400 years later, the market still looked like it belonged in the countryside – and, for a time, there was even a stream (the Vinohrady stream) flowing through it.

In 1678, a Baroque statue of St Wenceslas, by Jan Jiří Bendl (who also created several of the statues on Charles Bridge – see https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/09/prague-1-day-68-karluv-most-charles-bridge/), was placed on the square.

It was actually placed right in the middle of the square – where Vodičkova and Jindřišská are now – before being moved, in 1827, to where we now see Hotel Europa.

In March 1848, a radical Czech association, Repeal, held a meeting at Svatováclavské lázně (see https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/01/prague-2-day-150-dittrichova/ for more details).

One of the attendees, Karel Havlíček Borovský (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2022/12/26/prague-3-day-122-havlickovo-namesti/), proposed that Koňský trh be renamed Svatováclavské náměstí (St Wenceslas Square).

In June 1848, mass was held by the statue, a mass which was the inaugural moment of the (failed and bloody) 1848 Prague Uprising.

Once the Horse Gate (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/09/17/prague-1-day-122-mezibranska/) at the top of the square was demolished, it was replaced by the National Museum (1885-1890). What a building.

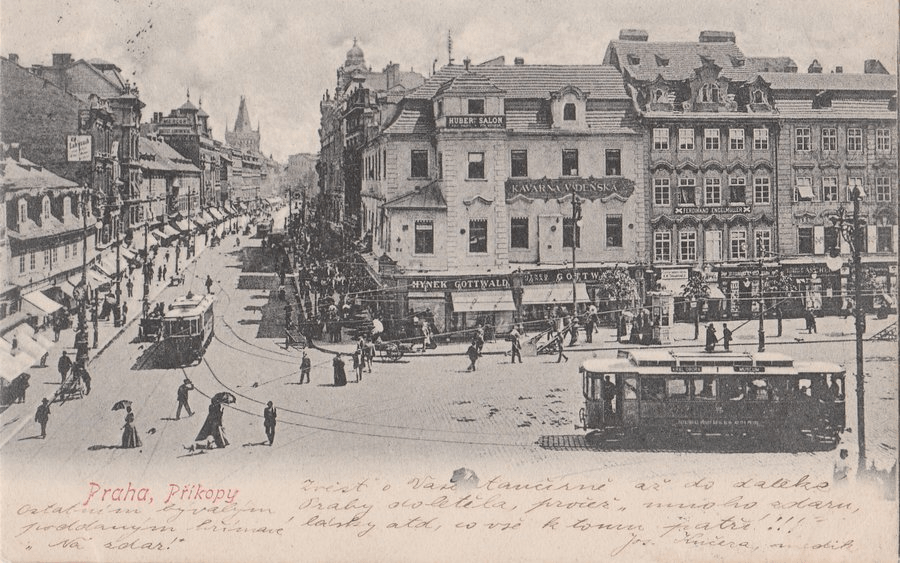

Also in the ‘hard to imagine now’ category, it was only around this time that the square was introduced to paving and streetlights. Trams started running along the square in 1884 (and ran until 1980).

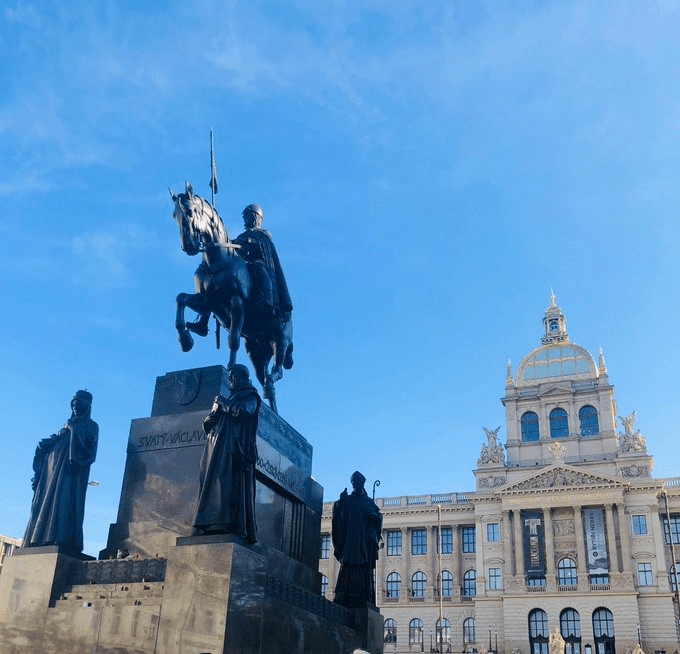

Bendl’s statue got moved to Vyšehrad in 1879 – it’s still there – while a new statue by Josef Václav Myslbek was unveiled in 1913, but not completed until 1925.

You’ll recognise it.

You might just think the square is for tourists and anybody who is really into Popeye’s or Primark – but it has, of course, played a key role in many important moments in the country’s history.

On 28 October 1918, Isidor Zahradník declared an independent Czechoslovakia in front of a huge crowd.

During the Nazi occupation, the occupying powers (not the first noun that I wanted to write) used the square for their own demonstrations.

And, in 1968, Soviet troops fired on the National Museum because they thought it was the headquarters of Czech Radio.

Am I allowed to say ‘twats’? Twats.

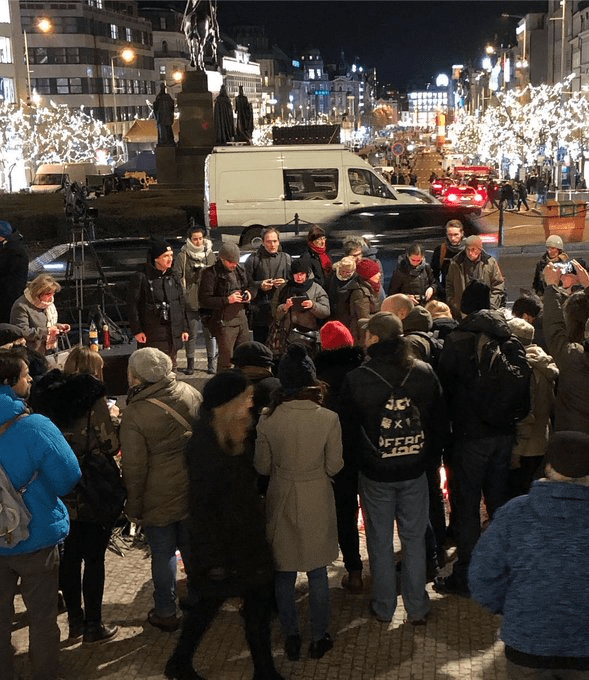

A few months later, this would be where Jan Palach set himself on fire in protest against post-Prague Spring demoralisation. Here are some pics I took during the commemorations of that event in 2019.

And many of us who aren’t Czech will have first seen Wenceslas Square in 1989, when it was the backdrop for the Velvet Revolution:

All the imperfections since, and I *still* get goosebumps watching this.

Václavák, as the locals call it, is constantly under reconstruction – the lower part is way more pleasant than it was a decade ago – and trams are due to make a comeback by the end of the decade.

For some reason, my oldest memory of Prague concerns a Reader’s Digest book my parents once had, and which I was obsessed with as a child.

The Guide to Places of the World included a two-page spread about Czechoslovakia – it was published in the 1980s, after all – with a photo of a rather foggy-looking Václavák, with trams going down it.

I have no idea why that picture stuck with me as strongly as it did – and I certainly wouldn’t go so far as to say that photo is ultimately the reason why I’m here – but it does make me particularly excited about the moment when the trams make a return.

There’s a lot of see on Václavák, although you may have to look up rather than directly in front of yourself to see the interesting, not-for-sale-not-aimed-at-tourists stuff. Join me.

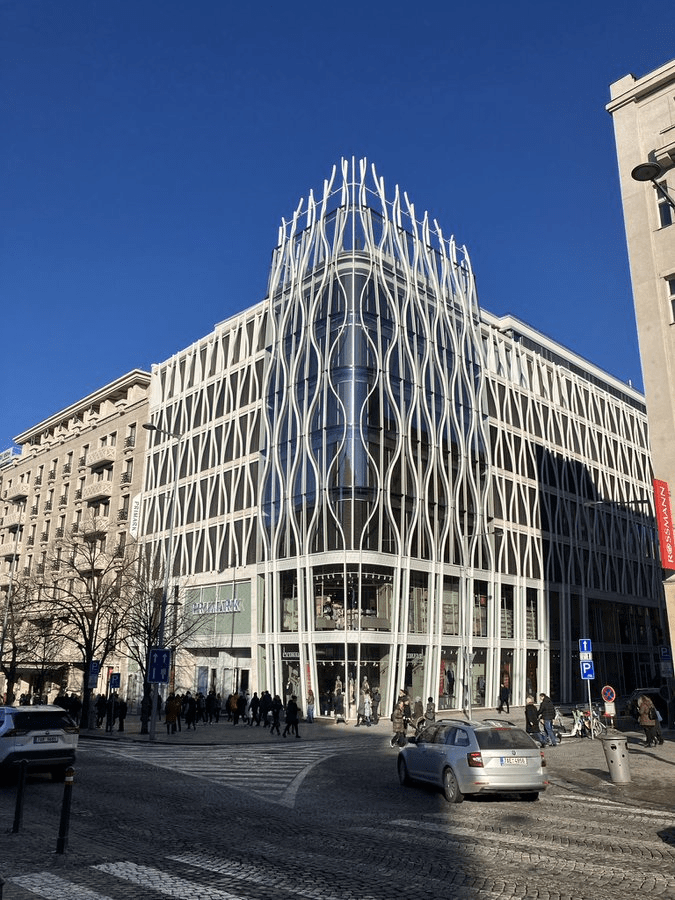

Number 47 is a particularly recent addition – the Flow Building (designed by the Chapman Taylor architectural studio, and completed in 2020), mainly known for making you realise Primark is extremely popular here.

It replaced the Neo-Renaissance Dům U Turků, built in 1880 and demolished in 2017. The decision was met with controversy, unsurprisingly, including a Facebook page which unsuccessfully campaigned for the decision to be reversed: https://t.co/gGvvxrRuL3

Here’s the building as it was: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:D%C5%AFm_U_Turk%C5%AF

Next door at number 45 is the socialist realist Hotel Jalta (1958). There’s an anti-nuclear shelter in the basement, which is now a museum about the Cold War (do go – it’s fascinating and the guides are great).

Number 41 is Luxor Palace; since 2002, it’s been the home of the Luxor bookshop, and I really hope I never find out how much money I’ve spent here in the last seventeen years.

Nearby is the building in whose courtyard Jan Zajíc, a 18-year-old student, killed himself by self-immolation on 25 February 1969, little over a month after Jan Palach had died.

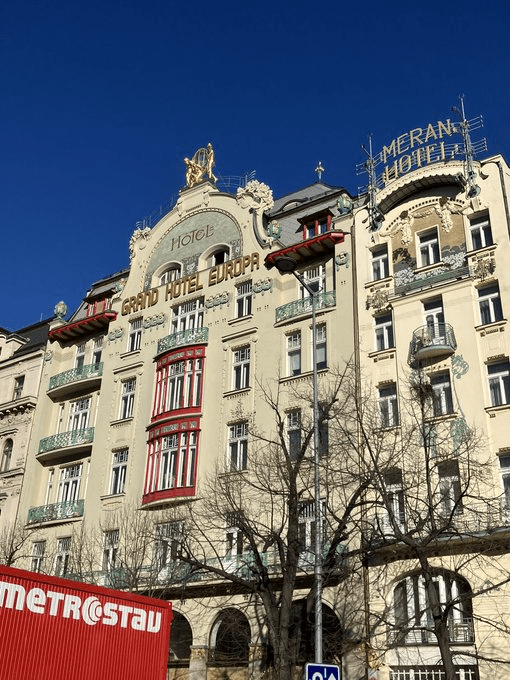

At number 25, Hotel Evropa was built in 1872, based on a design by Josef Schulz. It’s currently undergoing renovation, and you may have seen its interior during Mission: Impossible.

The exterior is pretty stunning too.

At number 19 is Palác Generali, built in 1895 and named after Assicurazioni Generali, an Italian insurance company. A local guy called Franz Kafka worked here from 1907 to 1908.

Another Art Deco hotel is at number 7 – Hotel Zlatá Husa (built in 1909 & 1910). It’s connected to number 5, Hotel Ambassador (built in 1922, and originally a department store).

On the corner, Palác Koruna (opened in 1914) hosted Prague’s first self-service restaurant, Automat Koruna, until 1992. It also hosted Prague’s answer to HMV or Virgin, Bontonland, which I visited with 24 hours of first arriving in Prague in 2005 and miss enormously.

Crossing over (or, let’s be fair, turning around – the square is 65 metres wide and there are no cars in this part), Palác Euro was added in 2002 and looks like it.

It’s next to the Lindt department store building, which, in the 1920s, had the square’s first glass facade. It also hosted Prague’s first ‘western-style’ bookshop (1998 to 2011), and yes, I miss that too.

Number 6, built in 1929, is the Baťa Shoe House – named after one of the most famous Czech brands, if not the most famous. They still operate a store in there.

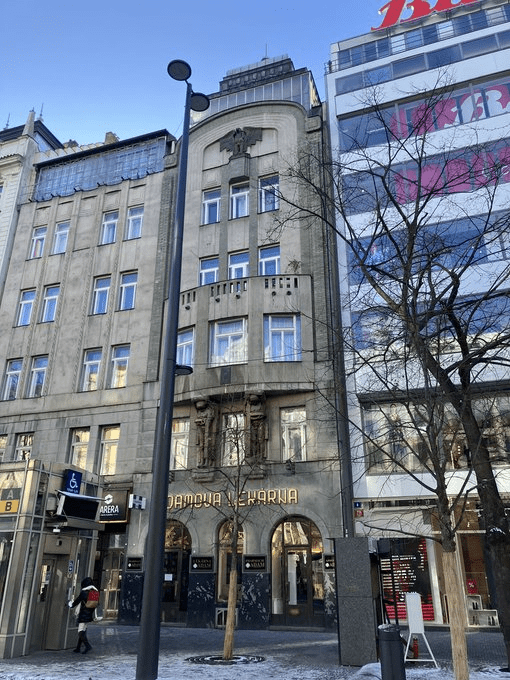

These glass buildings are quite a contrast to the most historical-looking Adam’s Pharmacy / Adamova lékárna, built between 1911 and 1912, and Peterkův dům, opened in 1899 and named after a banker called Peterka who had an apartment here.

Since 1996, number 14 has hosted Dobrá čajovna, a tea-house so successful that it has branches not only in Slovakia, Poland and Hungary, but also in the United States.

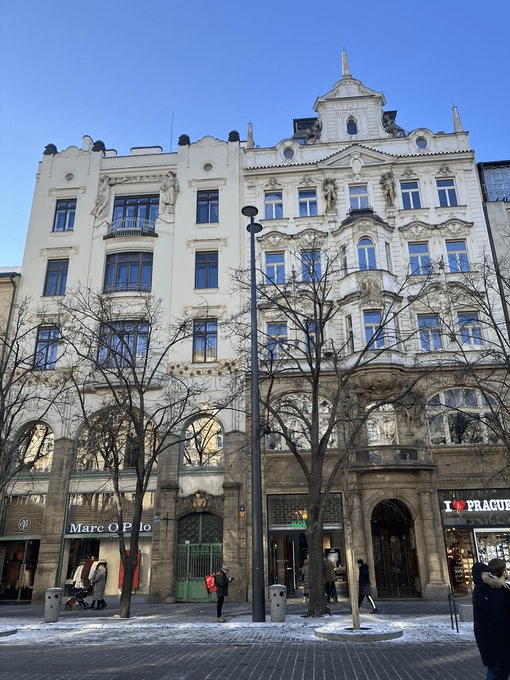

At number 18, the Neo-baroque Dům U Doušů (1898-9) replaced an inn which, in the 1700s, was the location for dances held by the Czech Estates, and was later used by Josef Kajetán Tyl (https://whatsinapraguestreetname.com/2024/07/01/prague-2-day-53-tylovo-namesti/) for social gatherings.

Its Neo-renaissance neighbour, Stutzikův dům (1886), meanwhile, sticks out for how much it’s now dwarfed by its neighbours.

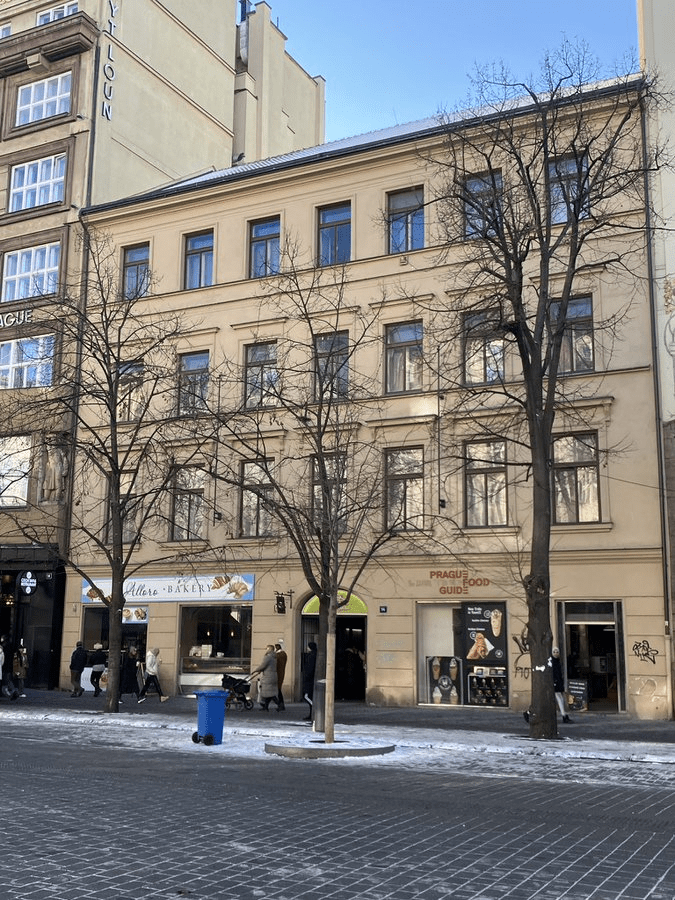

Such as Hotel Juliš (1922-5), which is next door. You may have heard of it when sent there by your kids (Sparky’s is a well-stocked toy shop), or when a fire occurred at the hotel in 2017: https://www.seznamzpravy.cz/clanek/na-vaclavskem-namesti-v-praze-horelo-z-hotelu-julis-hasici-evakuovali-70-lidi-34752

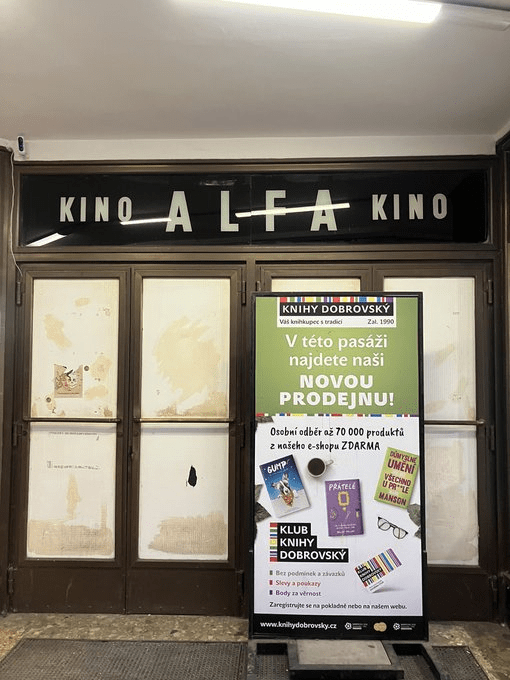

Palác U Stýblů (1928-9) used to be the home of the Semafor Theatre until it moved to Dejvice, as well as of Kino Alfa, a Prague institution that, sadly, hasn’t shown any films since 1994.

The Česká Banka Palace (built between 1913 & 1916) is the home of the Světozor Cinema, and was designed by Osvald Polívka, who was also responsible for the Assicurazioni Generali building right across the road, as well as, in part, Obecní dům and the New Town Hall on Karlák.

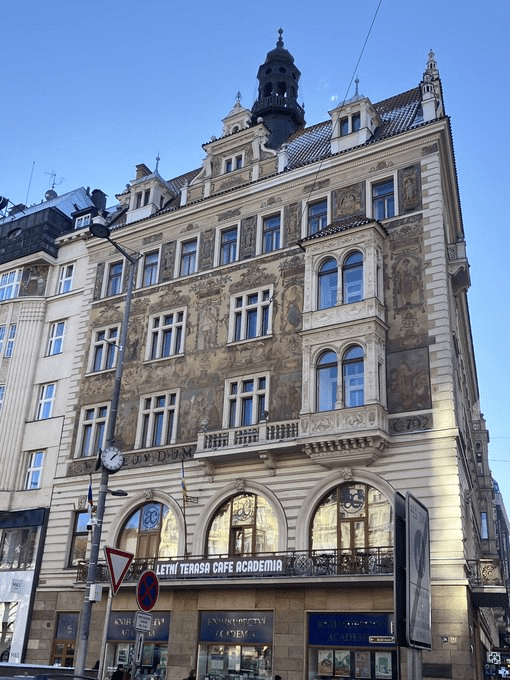

Right across from there is Wiehlův dům – home of the (excellent) Academia bookshop and publishing house. It has the best shop windows in Prague (example from the 30th anniversary of the Velvet Revolution).

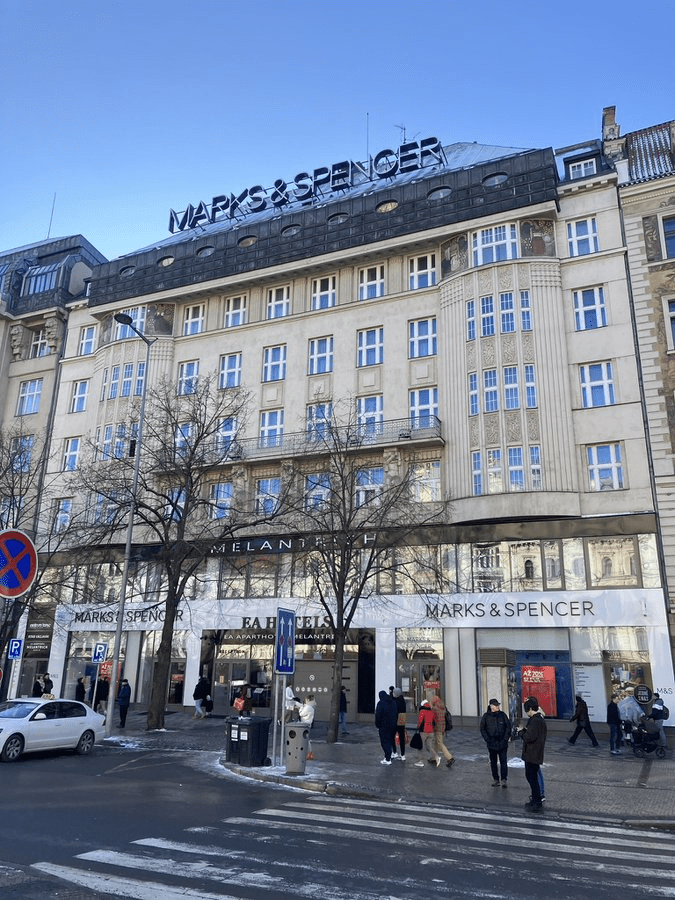

Next door, we Brits may know Palác Hvězda (1913) best for hosting M&S – but watch any clips from the Velvet Revolution in 1989, and this is the balcony people are most probably giving speeches from.

And neighbouring Palác Rokoko (1913-6) has been the home of the eponymous theatre ever since it opened.

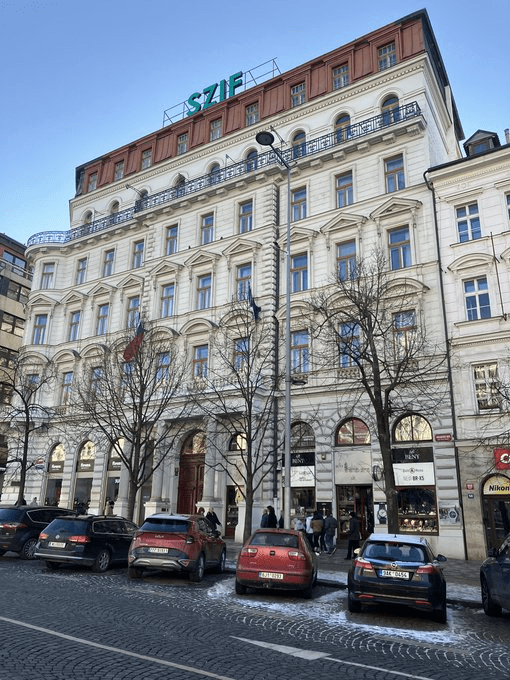

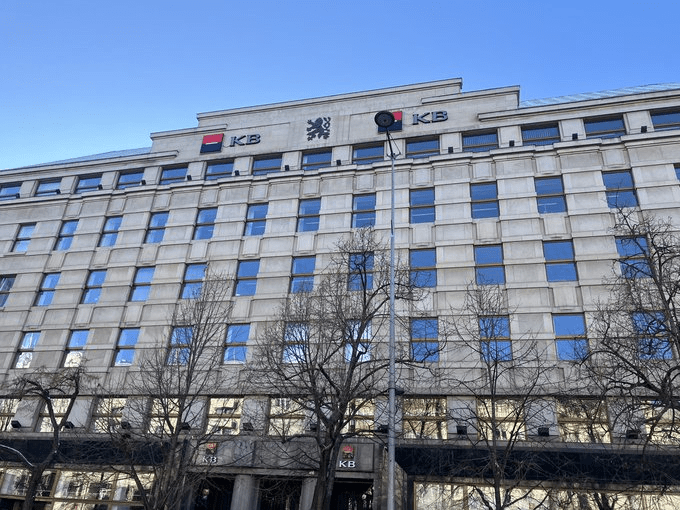

Up from here, you’ve got buildings owned/used by the State Agricultural Intervention Fund and Komerční Banka respectively. The latter has (had?) a paternoster which TERRIFIED me when I taught English in there for a time in 2007.

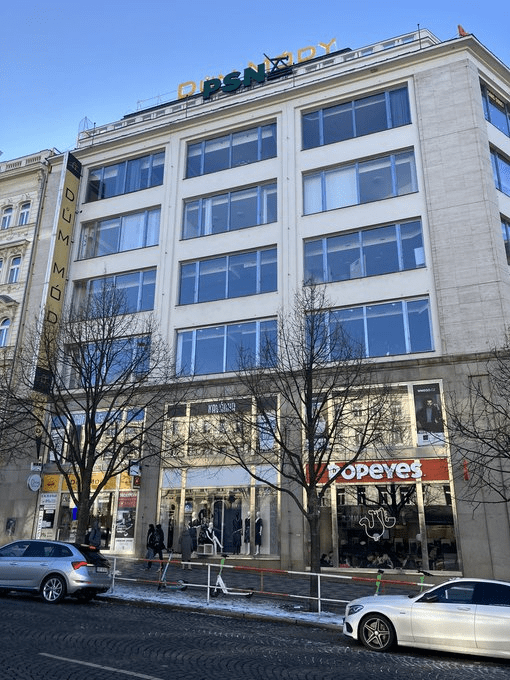

Palác Fénix (1927-30) was mentioned in a recent thread, while Dům módy (1954-6) hosted what was possibly the most glamorous, up-market department store in Czechoslovakia. Things change.

This thread is too long, and yet, when I went through it just now to see if anything could be eliminated, I not only failed to delete anything but also started worrying about all the things that I’d left out. And that is Prague in a nutshell, really.

Leave a comment